The United Kingdom's Reform Act of 1832

The Reform Act 1832 increased the number of available voters in Great Britain while also making voting more equitable. It did not, however, create universal suffrage. From the time of the first Parliament, in 1265, two burgesses had represented each borough and two knights had represented each county. It was left up to the House of Commons to decide on its membership, and so some Members of Parliament (MPs) effectively represented few or no other people. As the centuries went by, populations changed, with some settlement growing large enough and significant enough to become cities and other settlements declining in population, sometimes precipitously. Through all of these, the structure of the boroughs changed very little. By the time of the late 18th Century and early 19th Century, some huge disparities existed between populations of otherwise equally representative boroughs.

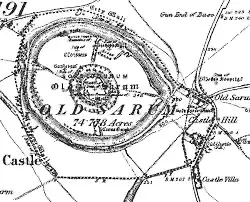

One particularly demonstrative example of the disparity in representation was that a very big city, like Manchester (with an 1801 population of 70,000), had no representation in Parliament and the borough of Dunwich, in Suffolk, had a population of 32 who elected two Members of Parliament (MPs). The latter were called rotten boroughs. One of the most famous was Old Sarum, which had 13 voters who elected two MPs. Another example of inequality were the pocket boroughs, so called because the MP was said to be "in the pocket" of a wealthy patron, having taken a large sum of money from that patron and tacitly agreed to vote the way the patron wanted. Parliament had tried to pass electoral reform before. Both William Pitt the Elder and William Pitt the Younger pursued such legislation; both times, the Houses of Commons said no. The Industrial Revolution brought more people together, drove up populations in factory centers, and created in workers a sense of togetherness and longing for entitlement that hadn't existed in a significant way. The idea of being more equitably represented in Parliament (for instance, in some cases, by being represented at all) grew in appeal. One thing that made the Reform Act of 1832 eminently possible was a change in government. In 1830, the Prime Minister was the Duke of Wellington, who was steadfastly opposed to parliamentary reform. His party, the Tories, controlled the government. Later that year, however, the other major political party, the Whigs, gained power and a new Prime Minister, Earl Grey, was in charge. Grey and his Whig supporters had vowed to seek voter reform, and so they did. It took them more than one attempt to get it. In 1831, the House of Commons, with its new Whig majority, passed a reform bill. The House of Lords, still controlled by the Tory Party, voted the bill down. Grey and other Whig leaders were frustrated and vowed to try again. Those in the cities and towns who supported reform took matters into their own hands, and the result was a series of riots across England, notably in Birmingham, Bristol, Derby, Exeter, Leicester, Nottingham, and Yeovil. The Bristol riots were particularly destructive, killing 12 people and resulting in 102 arrests; the rioters also set many houses and public buildings on fire. The king of Great Britain at the time, William IV, wasn't particularly enamored of parliamentary reform, but he did watch with great interest in July 1830, just after he became king, when the French people forced out the ruling monarch, Charles X, and replaced him with one who would agree to a constitutional monarchy, Louis-Philippe. (France, of course, had survived the French Revolution, a wholesale and violent reaction to the excesses of monarchy.) William eventually saw the need to get behind the reform movement and, as a partial solution, agreed to create new peers in the House of Lords who were members of the Whig Party, in order to create enough votes to pass a parliamentary reform bill. Hearing this, a number of existing peers changed their minds and approved the next reform bill.

The Reform Act 1832 (and the Parliamentary Boundaries Act) took away representation from 56 boroughs in England and Wales and dropped to one the representation in another 31 boroughs. The Act also created 67 new boroughs. Under the terms of the Act, a voter had to live in a home that had an annual value of £10. The Reform Act also widened the net for property qualification; as a result, now included were landowners, shopkeepers, and tenant farmers. The Reform Act increased the overall number of voters, from 435,000 to 652,000. The overall population, however, was 14 million. Despite the passage of the bill, the number of people who could vote was a small part of the total population. Those who lived in rural areas had property qualifications against them as well. Only 1 in 7 adult males could vote after the passage of this bill. Universal suffrage would have to wait, particularly for women, who were specifically prohibited from voting because the language of the Reform Act was such that as a voter defined as "a male person." |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White