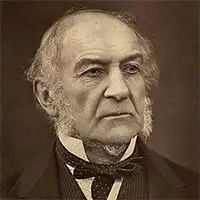

William Gladstone: Lion of Reform

Part 2: Longtime Leader Gladstone the leading lawmaker set about enacting more reform legislation. Among the first were two bills dealing with Ireland, the Irish Church Bill and the Irish Land Bill. The first allowed Irish Catholics to pay their tithes to their own church, rather than to the Church of England; The following year, Gladstone, under pressure, agreed to accept the Conservative Party's platform for what became the Trade Union Act 1871, which gave legal protection to trade unions. On the same day, Parliament passed the Criminal Law Amendment Act, criminalizing picketing. In 1872, Parliament passed the Ballot Act, which gave electoral reformers one of their long-cherished options: the secret ballot. Also in that year, Parliament passed the Licensing Act, which gave local authorities the power to control when public houses (known as pubs, which were the equivalent of bars) could open and whether they served alcohol at all. The general election of 1874 saw a reversal of fortunes for both major political parties, as the Conservatives won a majority in Parliament and Disraeli returned to being Prime Minister. Gladstone stepped down from the leadership of the Liberal Party but kept his seat in the House of Commons and took to writing political pamphlets. Meanwhile, Disraeli and the Conservatives enacted reforms of their own, including the Factory Act, Public health Act and Pure Food and Drugs Act–all geared toward improving the lives of people across the economic spectrum.

It was a fact that Queen Victoria enjoyed the company and politics of Disraeli much more than those of Gladstone. She is said to have commented to a friend, speaking of Gladstone, that "he speaks to me as if I were a public meeting." But the queen was persuaded after the Liberal victory in the 1880 general election to pass over a small handful of other worthy candidates and ask Gladstone if he wouldn't be Prime Minister just one more time. He agreed, on the condition that he, and not the queen, would choose the members of his Cabinet. She reluctantly agreed. Gladstone introduced a second Irish Land Bill in 1881. This one did more for tenants than the first one had and was embraced widely by the Commons and then passed narrowly by the House of Lords.

In 1884, Gladstone championed the Third Reform Bill, the net effect of which was to give all working class men the same voting rights as the men who lived in the boroughs. The House of Commons narrowly approved the bill, but the House of Lords rejected it. A mass demonstration of 30,000 people gathered in Hyde Park and the marched through London, advocating for passage of the reform bill. Gladstone reintroduced the reform bill, and it was passed by the Commons and then the Lords, but only after Gladstone had agreed to champion a subsequent bill redistributing seats in Parliament. After a brief resignation in 1885, Gladstone was back in power that same year after his Liberal Party won that year's general election. He introduced the Home Rule Bill for Ireland, which aimed to set up a separate parliament for Ireland and remove all Irish MPs from Westminster. The bill failed, and Gladstone resigned. Advanced in years but still fit, Gladstone continued as leader of the Liberal Party and, after that party's victory in the general election of 1892, became Prime Minister one more time. He enjoyed success with the passage of the Workmen's Compensation Act, giving more rights to injured workers, but suffered defeat with a second Irish Home Rule bill. That bill was again approved by the House of Commons and rejected by the House of Lords. Gladstone gave a speech in Parliament on March 1, 1894, that turned out to be his last. In the speech, he put forth an argument that the House of Lords should no longer have such a checkmate power over bills passed by the House of Commons. He resigned the following day. He stayed in Parliament until the following year, then left politics altogether. Gladstone died on May 19, 1898, of a heart attack. He was 88. He is remembered as a champion of reform and has been honored with statues and memorials in various cities across the U.K. Named after him have been towns, buildings, streets, and parks, in multiple countries. First page > Rise to Success > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

the second gave tenants more rights in regard to their landowners. A much more consequential reform bill was the Education Act 1870, which divided the country into 2,500 school districts, each with elected school boards that could make their own bylaws and either charge fees or allow students to attend for free. This law did not prevent women from voting for members of school boards or from running themselves to be on a school board; in its first year, voters elected four women to school boards.

the second gave tenants more rights in regard to their landowners. A much more consequential reform bill was the Education Act 1870, which divided the country into 2,500 school districts, each with elected school boards that could make their own bylaws and either charge fees or allow students to attend for free. This law did not prevent women from voting for members of school boards or from running themselves to be on a school board; in its first year, voters elected four women to school boards.