Ireland from the U.K. to Republic

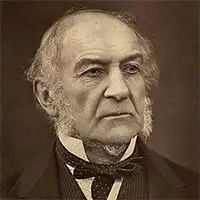

Gladstone had been a supporter of reform in his first time as Prime Minister. In 1868, he had introduced and championed the Irish Church Bill and the Irish Land Bill. The first allowed Irish Catholics to pay their tithes to their own church, rather than to the Church of England; the second gave tenants more rights in regard to their landowners. He had also introduced a second Irish Land Bill in 1881. This one did more for tenants than the first one had and was embraced widely by the Commons and then passed narrowly by the House of Lords. The climate in the 1880s and 1890s was very much against the wholesale changes that the Home Rule bills promised, however. Gladstone tried again in 1893, with the same negative result. This time, he had won passage in the House of Commons; the result in the House of Lords was overwhelmingly no, however. Also in the 1880s came the Irish Unionist Party (IUP), who wanted the exact opposite of what Gladstone and others were urging in the drive toward Home Rule. The members of the IUP wanted to stay as members of the U.K.

In 1893, a number of Irish nationalists led by author Douglas Hyde (right) founded the Gaelic League, with the goal of bringing back Gaelic as the country's main language. The League set up language classes and poetry festivals and printed magazines with the words in Gaelic. Noted writer W.B. Yeats became the first president of the Irish Literacy Society in 1892. A related organization was the Gaelic Athletic Association, formed to promote the prioritization of hurling and other home-grown sports. The Gaelic-centric organizations were careful to refrain from making public statements or arguments and had no interest in sending members to Parliament. Others in Ireland wanted to pursue every possible avenue to bring about Home Rule. In 1901, Arthur Griffith, the editor of the newspaper the United Irishman, launched a political organization called the Society of the Gaels. Griffith had no violence in mind; rather, he promoted two nonviolent forms of resistance. He urged Irish people not to pay taxes, and he suggested that Irish people elected to the U.K. Parliament should form their own council in Ireland instead. He had a name for his policy: Sinn Féin. Parliament introduced a third Home Rule Bill in 1912. By this time, tempers were running high on both sides of the debate. Unionists formed a paramilitary organization called the Ulster Volunteers; home rule supporters countered by forming the Irish Volunteers. Both sides had weapons. In a sense, the introduction of the Home Rule bill had come about because of political expediency. King Edward VII had died in 1910, and George V took the throne. One of the new king's first big challenges was the constitutional crisis that had arisen from the "People's Budget" of 1909. The House of Commons had approved the budget, but the House of Lords had rejected it. King Edward had refused to voice his approval of an increase in the number of Members of Parliament in order to pass the 1909 "People's Budget," which called for a suite of taxes on the rich in order to finance a spate of social welfare programs. Prime Minister H.H. Asquith had urged King Edward to swell the Liberal members of the House of Lords such that that body would then have a majority who were in favor of the new budget. Edward refused, saying that such an issue should be decided by the people directly, by way of a general election. The issue continued because the ensuing election didn't provide enough change in parliamentary membership to make a difference. Finally breaking the deadlock was a bill that changed the power of the House of Lords to outright veto a bill that the Commons had passed and instead gave the Lords the right to delay passage of such a bill for a maximum of two years. By the time the issue was resolved, Edward had died and George was king. George sorted things out by agreeing to do what Edward had not, create new members of the House of Lords who would approve the "People's Budget." As it turned out, the king didn't have to take that extraordinary step because the Lords agreed to a new version of the budget bill and, further, to the Parliament Act 1911, which curtailed its power. That the "People's Budget" had passed the House of Commons at all was due in large part to the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), led by John Redmond. The IPP had pledged to support Asquith and his budget if he and his party in return agreed to introduce another Home Rule bill. Asquith kept his end of the bargain, and the result provided for a two-house Irish Parliament in Dublin and a continuance of Irish representation in the U.K. Parliament (although with a reduction from 103 seats to 42). Finally, in 1914, Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1914. Notably, it took the Commons three tries to get the Home Rule bill passed. After three straight instances of the House of Lords' rejecting the bill (in 1912, 1913, and 1914), the Commons invoked the Parliament Act 1911 and sent the bill to King George V for Royal Assent, which he granted. However, the timing was such that World War I had begun. The U.K. Government put the Home Rule bill on hold pending the end of the war. Many people throughout Europe in 1914 thought that the war, even though it had started in August, would be finished by the end of the year. It

dragged on and on and on. A large group of people in Ireland decided that they didn't want to wait any longer. On Easter Monday 1916, which was April 24, a group of 1,200 protesters, armed with guns and other weapons, stormed through various locations across Dublin, taking control of the General The death toll for those in rebellion was 64. U.K. authorities executed 15 leaders of the uprising and imprisoned 1,500 of those who rose up with them. Casualties among the civilian population numbered 220. Meanwhile, thousands of Irishmen were fighting and dying in Europe, fighting under the U.K. banner. The participants in the Easter Rising were the exception: Both Unionists and Home Rule proponents supported participation in the war effort–on behalf of the Allies. Next page > The Drive to Independence > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

In the 1880s, the Home Rule movement got a powerful new ally,

In the 1880s, the Home Rule movement got a powerful new ally,  Post Office. Those taking part in what came to be known as the Easter Rising were from the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Irish Volunteers, and the Irish Citizen's Army. The fighting was at times severe and lasted five days. Leading the Rising were two writers, the poet Patrick Pearse and the journalist James Connolly. They had planned on receiving a shipment of weapons from Europe, in a plot carried out by Roger Casement, who had persuaded Germany to send 20,000 riles and 5 million rounds of ammunition to help Ireland attack England. The British Navy sunk the German ship that was carrying the munitions reinforcements, leaving Pearse and Connolly wondering when the cavalry was coming. They seized nearly two dozen significant buildings and locations that day. U.K. troops fought back with ferocity, leveling the Post Office building and eventually retaking all of the seized locations, forcing mass surrenders. It took five days, but it was all over by Friday.

Post Office. Those taking part in what came to be known as the Easter Rising were from the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Irish Volunteers, and the Irish Citizen's Army. The fighting was at times severe and lasted five days. Leading the Rising were two writers, the poet Patrick Pearse and the journalist James Connolly. They had planned on receiving a shipment of weapons from Europe, in a plot carried out by Roger Casement, who had persuaded Germany to send 20,000 riles and 5 million rounds of ammunition to help Ireland attack England. The British Navy sunk the German ship that was carrying the munitions reinforcements, leaving Pearse and Connolly wondering when the cavalry was coming. They seized nearly two dozen significant buildings and locations that day. U.K. troops fought back with ferocity, leveling the Post Office building and eventually retaking all of the seized locations, forcing mass surrenders. It took five days, but it was all over by Friday.