Ireland in the 17th and 18th Centuries

The Tudor return to dominance in Ireland had begun ostensibly with the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, who oversaw the implementation of the Poynings' Law. Named after the Lord Deputy of Ireland, the 1494 law stipulated that the Irish parliament could not be summoned without permission of England's privy council and that all laws passed by the English parliament also applied to Ireland.

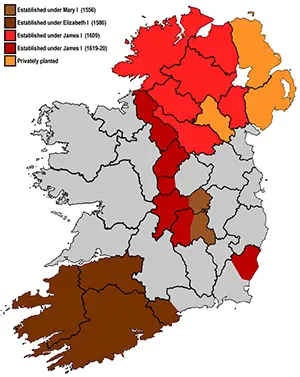

Henry VII's successor, his son King Henry VIII, brought an army with him in 1534 and stayed for nearly a decade, during which time the Irish named him head of the Irish Church and King of Ireland. Henry's son Edward VI began the "plantation system," which continued to create conflict through the years, accelerated as it was by both of Edward's sisters, Queen Mary I and Queen Elizabeth I, who oversaw the implementation of the Plantation of Munster. The large-scale rebellion led by Hugh O'Neil ended in military defeat and, in 1607, in the Flight of the Earls, as O'Neill, the Earl of Tyrconnell Rory O'Donnell, and a large handful of other Gaelic lords left Ireland for the Continent, in an attempt to raise money and men to turn back the English "planting." Once they left, the English Crown seized their lands. The first Stuart monarch, King James I, took advantage of O'Neill's absence to create a large plantation on the earl's former lands, and this became the Plantation of Ulster. A large-scale scheme of surveying and land division ensued, by a large-scale recruitment of tenant farmers from England and Scotland. A quarter century later, the Ulster settlement boasted a population of 50,000, the vast majority of them Protestant. Also during this time, Protestants formed a majority in the Irish parliament. In 1641, as England was consumed the English Civil Wars, a large number of Gaelic and Norman landowners led by Phelim O'Neill (son-in-law of Hugh O'Neill) struck back against their English overlords. Targeting plantation settlers in particular, the Irish cut a swathe of violence through Ulster and surrounding areas, leaving 4,000 dead. Munster was particularly hard hit as well. This prompted a large military response from England, even as the forces of King Charles I were involved in fighting in Scotland. English troops turned back the tide of the Irish rebellion for a bit but were recalled when the English Civil Wars began.

Also in 1642, an alliance of Irish and Anglo-Irish in the south of Ireland formed the Confederation of Kilkenny and retook the vast majority of their Ireland. Still in the English Crown's hands were Dublin and a handful of other towns. The Confederation was happy for the Royalists and the Parliamentarians to fight each other to a standstill in England but, when forced to choose sides, allied themselves with the Royalists, who promised self-government and full rights for Catholics. The parliamentarian side triumphed, even executing the king, and the new nominal leader of England was Oliver Cromwell, who wasted no time in bringing a large contingent of his New Model Army to Ireland in 1649. English troops landed in August and set about reconquering Ireland.

The first major target was Drogheda, which English troops besieged into submission, then massacred those who had surrendered. This was but one of many acts of cruelty committed by English soldiers. (Such acts of violence had become altogether common during the wars of the past few centuries.) One other took place at Wexford. While negotiators were determining the terms of surrender, parliamentarian troops stormed the town, burned it, and killed more than 1,000 townspeople. Cromwell's forces then took other port cities, including Duncannon and Waterford. A prize conquest for the English force was the taking of Kilkenny, capital of the Confederation. In 1650, English forces defeated the Ulster Army and then, during the next few months, took the last two Irish strongholds, saying siege to the strongly walled cities of Limerick and Galway and eventually claiming them both. The remaining pockets of Irish resistance relied on guerrilla tactics for the next couple of years, and the last defenders of the Irish-Royalist cause surrendered in April 1653. Cromwell had left Ireland in 1650 to fight in Scotland; his son-in-law, Henry Ireton, completed the reconquest. English authorities then set about forcibly moving Irish people into the western province of Connaught, so that English people can live in the other three-quarters of the island. Irish who didn't want to move were threatened with imprisonment or deportation. Indeed, English officials during this time send a large number of captured Irish soldiers and sympathizers offshore as indentured servants, to the Caribbean. King Charles II in 1665 introduced the Act of Explanation, which one-third of land that Cromwell's Commonwealth had taken from the Irish to be returned. Even more palatable to Irish people was the ascension to the English throne of Charles's brother, James II, who appointed Catholics to several high-profile posts, including Richard Talbot Earl of Tyrconnell, who was named Commander of the Irish Army and the Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Talbot it was who maintained his loyalty to James II (left) when the latter fled England and his throne in 1688. When James mounted an invasion of England the following year, he went first to Ireland, landing in Kinsale and then marching to Dublin, where he was hailed as the rightwise King of England. James and his army attacked the Protestant strongholds of Enniskillen, Londonderry, and Ulster, all of which withstood the incursions. And English arrived in June 1689, but neither side made headway for the rest of that year.

France's Louis XIV, who had encouraged James with words, sent along men and munitions in the thousands to fight for a fellow Catholic monarch. England's William III arrived in June to head up the English force. In the resulting confrontation, the Battle of the Boyne, the English gained the upper hand not on the battlefield itself but afterward, when James II fled again to France, never to return. Irish forces fought on, and the two exhausted two sides agreed to a peace agreement, the Treaty of Limerick, in October 1691. Next page > The 18th Century > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White