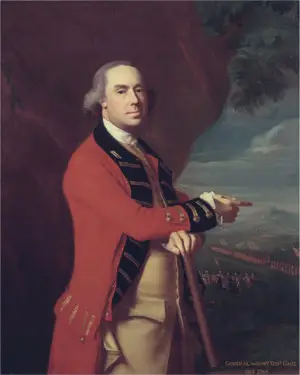

Thomas Gage: Redcoat Commander

Thomas Gage was a soldier known for his role as commander-in-chief of British forces in North America in the 1770s.

He entered military service in 1741 and worked his way up to captain in 1744. In that year, he served as aide to the Duke of Albermarle at the Battle of Fortenay in 1744, at the Battle of Culloden the following year, and again in the Low Countries two years after that. He was named lieutenant colonel in 1751. Among the friends he made during this time was a future opponent, Charles Lee, who would go on to command troops in the Continental Army. He went with his regiment to North America in 1754, to fight in the French and Indian War. He was with General Edward Braddock at the Battle of the Monongahela, which killed both Braddock and Gage's regimental commander, Col. Peter Halkett. Gage himself was slightly wounded in the battle. Another officer, Captain Robert Orme, accused Gage of poor military tactics during the battle; Gage later cleared his name, but the incident prevented him from advancing to command of the regiment. Also on this campaign was a young George Washington; he and Gage stayed in contact for a few years. In 1757, Gage got a promotion, to the rank of colonel, and set about recruiting for a new unit. Fitted out and ready to go, he led his troops in an assault on Fort Ticonderoga in July 1758; the action did not succeed, and Gage was wounded again.

He went to New York City, for two purposes: to meet with Jeffery Amherst, his commander-in-chief, and to get married, to Margaret Kemble. Gage gained a new assignment, commanding Albany and surrounds, in January 1759. Amherst tasked Gage with capturing Fort La Galette and the city of Montreal. Gage responded with a counter-proposal that saw Amherst and Major General James Wolfe move into Canada while Gage reinforced Niagara and Oswego instead. Amherst didn't take kindly to the suggestion and put Gage in charge of the rear guard for the attack on Montreal. When the British took the city, Amherst left Gage behind as military governor. Gage gained the rank of major general in 1761 and, after Amherst left North American for good, was named commander-in-chief. The war was over, and Great Britain had defeated France, but some Native American tribes still had to be dealt with; among those was the Ottawa leader Pontiac, who organized a sustained rebellion against British forces that ended only after a few more years. In the meantime, the British Government had set about imposing new taxes on the American colonists, in an effort to share the load of repaying the war debt. Among the more contentious of these tax provisions was the Stamp Act, a 1765 tax on essentially paper that resulted in large-scale protests throughout the 13 Colonies, the formation of a Stamp Act congress, and the eventual repeal of the tax. Gage recalled troops from the frontier and installed them in coastal cities, to keep the peace; to provide for this redeployment, Parliament passed the Quartering Act, which required American colonists to provide food and shelter for British troops so stationed. A further set of taxes, the Townshend Acts, further inflamed the situation, particularly in Boston, and Gage Gage was back in Great Britain in 1772 and 1773 and returned to North America in April 1774, replacing Thomas Hutchinson as governor of Massachusetts. At first, Boston residents were happy that Gage wasn't Hutchinson, who had become deeply unpopular. However, when Gage reinforced the idea that the colonists would have to comply with the Intolerable Acts, he, too, found himself disfavored. Fearful of an armed uprising, Gage dispatched groups of troops to seize weapons and ammunition

A timely arrival of reinforcements under Major General William Howe gave Gage confidence to strike. His first move was to remove colonial forces who had fortified Breeds Hill, north of the city of Boston. The resulting skirmish, which came to be known as the Battle of Bunker Hill, was a Pyrrhic victory in that British troops seized the hill but lost 1,000 men in the process. Not longer afterward, the British war department recalled Gage to Britain, replacing him with Howe. Gage never returned to North America. He did tell his superiors that he was convinced that only a very large armed force, supplemented by foreign mercenaries, would be able to defeat the determined colonists. He was placed on the inactive list and reactivated in April 1781, as part of an effort to protect against a possible invasion by France, which had entered the war on the side of the Americans. Gage was promoted to the rank of full general in November 1782 but again saw no action. He died on April 2, 1787, on the Isle of Portland. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

sent a large contingent of troops to that city. Tensions boiled over in March 1770, in what later was called the

sent a large contingent of troops to that city. Tensions boiled over in March 1770, in what later was called the  throughout the northeast, starting with Somerville, Mass. One of these expeditions resulted in the "Shot Heard 'Round the World," the twin conflicts of

throughout the northeast, starting with Somerville, Mass. One of these expeditions resulted in the "Shot Heard 'Round the World," the twin conflicts of