Pontiac: Ottawa War Leader

Pontiac was a leader of an Ottawa tribe who fought with French soldiers against the British in North America in the 1750s and 1760s and was more well-known for leading a series of attacks on British soldiers and forts in 1763. Not much is known of his early life. He is thought to have been born about 1720, possibly to parents of different tribes, possibly near Detroit. Tall and strong, he exhibited qualities necessary for a leader. His fighting process was an asset in this as well. He is known to have married once, to Kantuckeegan, and had two sons.

Pontiac was a leader in the Ottawa tribes by 1747. Like many Native Americans, he fought alongside French forces during the French and Indian War. Some sources say that he fought in the defeat of British Gen. Edward Braddock in 1755. He is known to have taken part in a few other battles during the war, all against the British. In February 1763, France and Great Britain signed the Treaty of Paris, officially ending the war. France agreed to give up all of its North American territory, handing it over to Great Britain. French explorers and settlers had been much more welcome to enter into trade agreements and co-exist as neighbors than had British settlers and troops. Right away, the British in the Great Lakes region and elsewhere made a series of changes, some highly significant. British settlers increased the area of land on which they built new houses and other buildings, regardless of whether Native Americans lived nearby. British military leaders also stopped their traders from exchanging money and goods with Native Americans. Just two months later, Pontiac gathered a number of Native Americans from a number of tribes and set up a plan for attacking British forts in the Great Lakes region. He thought that such an effort would result in his people's gaining much-needed ammunition and supplies; he also hoped that the seizure of a number of forts would convince French traders to return.

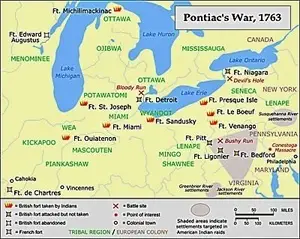

On May 7, Pontiac and 300 tribesmen from more than a dozen nations walked into Fort Detroit with blankets draped over their shoulders; inside the blankets were sawed off shotguns. Pontiac was clearly holding a wampum belt that he said he wanted to present to the Fort Detroit commander, Major Henry Gladwin, as a gesture of good faith. In fact, the presenting of the belt was a signal to Pontiac's men to attack. Gladwin had been tipped off, however, and he and his men pointed weapons at Pontiac and his men, who had yet to unveil theirs. Two days later, Pontiac tried again and was again rebuffed. The Native Americans took out their frustrations on the villagers living near the fort and began what was effectively a siege, denying fort residents reinforcements and supplies delivery. Reinforcements flocked to Pontiac's side, resulting in nearly 1,000. Elsewhere, other members of other tribes attacked other forts owned by Britain.

Pontiac never did take Fort Detroit. The British were able to withstand the siege, and Pontiac eventually called off his attacks, after hearing of the Treaty of Paris, by the terms of which France had agreed to leave North America for good. (It took several months for word to reach the frontier.) Native Americans elsewhere were having more success; in all, tribesmen captured nine of the 11 British-owned forts in the Great Lakes region. After the furious start to what has come to be called Pontiac's Rebellion or Pontiac's War, the two sides settled in for a series of sporadic attacks that dragged on for nearly three years. Both sides wearied of the fighting and looked to end it. Pontiac and Britain's Superintendent of Indian Affairs Sir William Johnson met at Fort Ontario on July 25, 1766; the result was an end of hostilities. British troops eventually recovered all of the forts captured by Native Americans and strengthened their defenses. No further Native American attacks on these sorts occurred. After these events, Pontiac faded back into the fabric of history for a couple of years. He testified in a murder investigation in 1767 and was ousted as a chief of the Ottawa in 1768. He was killed in a reported revenge crime on April 20, 1769, many sources near Cahokia, a French town. Pontiac is remembered as a well-known Ottawa chief willing to fight for his people's right to maintain their traditions. His legacy lives on in the name of Michigan's largest city. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White