The South Sea Bubble

The South Sea Bubble was an 18th Century stock share price crash that ruined hundreds of lives across the class spectrum of Great Britain.

Great Britain formed the South Sea Company in 1711, during the War of the Spanish Succession. The South Sea in the name of the company referred to the bodies of water around South America. At the same time as the company formed, it was granted a monopoly on trade with South America and nearby islands. (Part of that trade was in African slaves.) The real reason for the formation of the South Sea Company was to pay off Great Britain's national debt, which had increased markedly during the war. As to why the Lord Treasurer, Robert Harley, didn't just set up a bank to deal with the debt, the charter granted to the Bank of England, which debuted in 1694, gave that entity exclusive rights as the country's only joint stock bank.

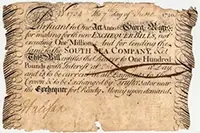

The idea was based on one already put into practice by John Law in France: A company (in this case the South Sea Company) would take on the national debt in exchange for equity (meaning shares) in the company that could be traded easily. In effect, the company bought the government debt and then planned to pay dividends to the company's shareholders by using interest from the government debt, which was in the form of bonds. In a trial case, the South Sea Company exchanged £1 million of government debt for shares of stock in the company. Because the amount of government debt had overnight dropped by £1 million, the overall amount that the government had to pay on its debt was smaller. At the same time, those who still held bonds on which the government paid could claim an increase in value of those bonds. More importantly to the South Sea Company, it made a tidy profit out of the arrangement. All involved judged it a worthy and successful experiment. The following year, the people behind the project suggested a much larger exchange.

The national debt in 1719, inflated again by yet another war in Europe, was £50 million. The South Sea Company assumed all of that debt, in exchange for shares in the company. Right away, people began buying up shared in the South Sea Company. Almost overnight, the share price increased tenfold. Rich people poured money into the company. Poor people borrowed heavily to get in on the scheme. Among those who took part were more than 500 members of Parliament. The following year saw the most dramatic price swings of all. Tracing the stock price:

As the price dropped, many people sold, in a frenzy. However, a great many more people did not or could not recoup their investments. Bankruptcies were rife. Families were ruined. Also losing substantial sums of money in the crash were King George I and his son, the Prince of Wales. The company had compounded the problem by, in August 1720, offering to lend people money so that they could turn around and buy shares in the company. At the same time, similar "bubbles" were bursting in France and the Netherlands. John Law's Mississippi Company had a spectacular collapse, resulting in great loss of wealth in France and also in investors in that company endeavoring to cash in their British investments by selling off their South Sea Company stock. A parliamentary investigation followed. The resulting report declared evidence of widespread corruption and fraud, including that conducted by members of the Cabinet. Those in the know bought and sold at specific times, making money based on inside information. As well, the supporters of the scheme paid large sums of money to Members of Parliament in order to convince them to vote for the scheme. Among the accused were these:

Emerging relatively unscathed from the South Sea affair was Robert Walpole, who in 1721 took over as both First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer. Walpole basically ran the government for the next two decades and is considered to have been the first Prime Minister (although the term wasn't used at that time). Walpole's government enacted measures to prevent such a scheme from occurring again. The South Sea Company, meanwhile, continued to be a trading company, facilitating trade between Britain and Spain, until 1763. The company continued in its role managing the government debt until 1853. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White