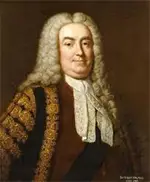

Sir Robert Walpole: Great Britain's Prime Minister

Sir Robert Walpole was the first and longest-serving Prime Minister of Great Britain, serving under the first two Hanoverian Kings George.

He was born on Aug. 26, 1676, in Houghton, Norfolk. His parents, Robert and Mary, had 19 children. He attended a private school at Massingham, in Norfolk, and then attended Eton College from 1690 and King's College, Cambridge from 1696. His stay at Cambridge was only two years; the death of his oldest brother meant that he was to look after the family household, and so he returned home in 1698. Two years later, he married Catherine Shorter; they had five children. He then followed in his father's footsteps, in 1701 becoming a Member of Parliament to represent Castle Rising, in Norfolk. In the next election, he won the seat at King's Lynn. A lifelong member of the Whig Party, Walpole rose through the ranks, being named to the Admiralty Board, serving as Secretary of War in 1708 and then Treasurer of the Navy in 1710–1711. He ran afoul of a number of members of the other large political party of the day, the Tories. He was impeached on charges of corruption in 1712, found guilty, and served time in the Tower of London. He was re-elected in 1713. The new monarch in 1714 was King George I, and Walpole, again in the political mix, led a Whig resurgence to a strong majority in Parliament. The very next few year, King George named him First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer. Walpole succeeded Lord Halifax, who had died while in office. Walpole resigned his positions in a dispute with two other members of the king's cabinet, Lord Stanhope and the Earl of Sunderland, but remained in Parliament and then rejoined the cabinet a few years later. During his time out of cabinet, Walpole led the opposition to one of Sunderland's signature bills, the Peerage Bill, which sought to limit the size of the House of Lords. The political dispute also resulted in a familial schism between the king and his son, also named George. Walpole later played a role in their reconciliation. He was paymaster general in 1720, the year of the South Sea Bubble. The Government had named the South Sea Company, a trading venture, to assume the country's national debt, in exchange for the company's issuing bonds. The idea was that the company would make a great deal of money through international trade and then the people who had bought shares in the company would get very rich. The share price dropped precipitously, and many people lost lots of money. An investigating committee found evidence of corruption involving numerous government officials.

Walpole, who had invested in the South Sea Company several years before but had sold all his shares, was one of the relatively few who avoided economic misfortune and political recriminations as the result of the scandal, and he regained his former top positions in 1721. It was in this year that later historians have referred to him as acting in the capacity of the Prime Minister, the chief member of government. The term Prime Minister was not used at the time, but Walpole was certainly chief minister not only to George I but also to his successor, George II, who took the throne in 1727. After a brief interlude in which he thought himself out of favor with the new king, he resumed his prime-minister-equivalent duties, thanks in large part to the intervention of Queen Caroline, who was a friend. In 1735, the new king George rewarded him with a residence, at 10 Downing Street. (This is still the residence of the Prime Minister of what is now the United Kingdom.) Walpole of all the chief ministers emerged relatively unscathed from the scandal and, in 1721, became the realm's first Prime Minister. After the South Sea scandal, the king attended very few cabinet meetings, leaving Walpole to run the government. George spent more and more time at his ancestral home, in Hanover. One thing that the king and Walpole did collaborate on in George's later reign was the establishment in 1725 of the Order of the Bath, an order of chivalry that was championed by John Anstis. The order exists to this day. The king named Walpole a Knight of the Garter as well. Also in Walpole's first year at the helm, another plot to restore the son of James II to the throne came out into the open. The main perpetrator, Francis Atterbury, was imprisoned in the Tower of London and then banished. Walpole enjoyed the favor of the king and of many in the Whig Party. He also had many enemies, among them Lord Bolingbroke and William Pulteney, who ran a publication title The Craftsman that regularly criticized Walpole and his policies. Also targeting Walpole were the satirist Jonathan Swift, most well-known for penning Gulliver's Travels, Alexander Pope, and John Gay, who skewered him in The Beggar's Opera. Walpole and the Whigs generally tried to avoid warfare. The Prime Minister convinced George II to avoid getting involved in yet another monarchical dispute, the 1733 War of the Polish Succession. Walpole sought to reduce taxes by not having to raise them in the first place, in order to pay for that troops and ammunition that would be required to fight a war. He reduced the land tax as well. Walpole also made extensive use of a sinking fund, designed to lower the national debt. The idea was to earmark in each year's budget an amount of money to be used exclusively to pay off a large bill, such as a public debt. Many governments were in the habit of raising money by issuing bonds, which would have to be repaid with interest. Using a sinking fund was effectively doing the opposite because no interest payment would be required. A change in the way that excise taxes on tobacco and wine were collected lost him much support, however, and a rare tax increase, on gin in 1736, resulted in riots in London. The year 1737 brought the death of Queen Caroline, Walpole's friend and adviser to the king. George II and Walpole still got along, but Walpole by this had lost some of his support in Parliament. Also, as had happened with his father, George II found himself estranged from his own son, George. Joining the Prince of Wales in publicly opposing Walpole were some of Britain's most famous future politicians, including William Pitt the Elder and George Grenville. A trade dispute with Spain escalated into an armed conflict, the War of Jenkins' Ear, in 1739. The next parliamentary election resulted in big losses by Walpole's Whigs, and he resigned in February 1742. King George II named him Earl of Orford, and he continued to advise the king after that. He died on March 18, 1745, in London. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White