Robert the Bruce: Hero of Scotland

Part 2: The Rise of the Bruce Scotland seethed, and some eventually took up arms against Edward. One of those was William Wallace, whose meteoric rise to power featured a stunning victory at Stirling Bridge in 1297 and an equally stunning defeat at Falkirk the following year. Wallace, in defeat, left the country. Scotland named Robert the Bruce and John Comyn as Guardians of Scotland. Both men eventually came to terms with Edward. Wallace returned in 1304 and tried to rally the troops again, but he was unsuccessful and was then betrayed and handed over to Edward, who had him killed. Bruce had married Isabella of Mar in 1295; she died a year later, after giving birth to a daughter, Marjorie. In 1302, he married again, to Elizabeth de Burgh. They eventually had four children.

Bruce and Comyn were uneasy co-regents, and they finally had an argument that turned deadly. At a church in Dumfries, Bruce silenced Comyn once and for all by stabbing him to death. Edward outlawed Bruce, and Pope Clement V excommunicated him. Undaunted, Bruce proclaimed himself King of Scotland. He was so crowned on March 25, 1306, with his wife at his side. Bruce's crowning as King of Scotland set off alarm bells in England, and Edward, who thought of himself as ruler of Scotland, raised an army to reiterate that point. Edward routed Bruce and the Scots twice in succession, and Bruce went into hiding in northern Ireland. It at this time that he had an arachnid encounter that is supposed to have inspired him to keep fighting. His spirits at a low after his defeats and amid his fear of being found out, Bruce became fascinated by a spider swing from one part of a cave roof to the next, again and again, in order to anchor its web. The spider had to try seven times before succeeding, but it did. Bruce is said to have taken from this new inspiration for maintaining his struggle to throw off the English yoke, and he came out of hiding and renewed the fight. The result was a Scottish victory at Loudoun Hill in 1307. Bruce then resorted to guerrilla warfare, and a greatly annoyed Edward raised yet another army, brought his son Edward along with him, and marched north. Edward I died, and his son became King Edward II. The new king led his army back to England, and Bruce and the Scottish forces continued to harass English castles and possessions in Scotland and in northern England. Edward became embroiled in a dispute with his barons that consumed the English court for a few years, during which time Bruce and his Scottish army had retaken most of the castles in Scotland that Edward I had controlled. In 1313, Bruce also demanded the loyalty of every Scottish noble who had not so far recognized him as King of Scotland, with the threat that their lands would be taken away if they did not submit. When word got to Edward II that only Stirling Castle remained in English hands and that Bruce's brother Edward was marching on it, King Edward sprang into action and rode hard for Stirling. Lying in wait was Robert the Bruce.

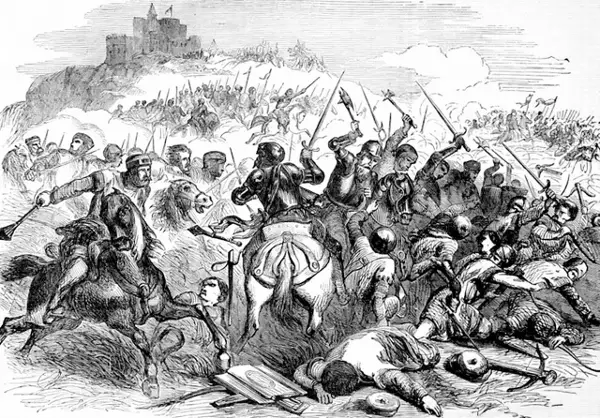

Historians generally agree that the Scottish forces were at the most half of the English forces on June 23, 1314, at the Battle of Bannockburn. Yet, Robert the Bruce and the Scottish forces won the day, ambushing a surprised Edward and his English forces, carrying on with what turned into a massacre, and nearly killing Edward himself. Edward had turned a well financed expedition that by rights should have resulted in a victory into a humiliating defeat. The Battle of Bannockburn humiliated Edward and nearly cost him his life and, as well, cost the lives of many an Englishman and Welshman. Edward wasn't done harassing Scotland, but he was still much more focused on things closer to home. Even though the Scottish army captured the final English stronghold at Berwick in 1318, Edward still refused to renounce his claim to be overlord of Scotland. In the meantime, Bruce and his fellow nobles got together, in 1320, and issued the Declaration of Arbroath, a statement to Pope John XXII that stated Scotland's right to independence. Four years later, the Pope recognized Bruce as the rightful ruler of Scotland. Bruce had thought to capitalize on his success and invade Ireland, with his brother Edward at the head of an army. That invasion was a disaster, and Edward gained a rare victory over Scottish forces. In 1322, Bruce and Edward agreed to a truce. Four years later, Scotland and France renewed their alliance. English forces led by Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer deposed Edward II in 1327, and the king's son Edward was crowned King Edward III. This king made peace with Scotland, and the 1328 Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton stipulated England's recognition that Scotland was an independent kingdom.

By this time, Bruce had been ill for his time. He is believed to have contracted leprosy, although chroniclers of the time used the word to describe many skin diseases. He died on June 7, 1329, at the Manor of Cardross, near Dumbarton. He was buried at Dunfermline. Bruce had ordered his heart taken to the Holy Land, as penance for his not going on Crusade and for killing Comyn in a church. The heart did not make it all the way there and was returned to Scotland, where it was buried in Melrose Abbey. His son David succeeded him on the throne, becoming King David II. Robert the Bruce is regarded as Scotland's foremost leader of the drive for independence. He is celebrated in monuments, statues, castles, and all manner of songs, plays, books, and other kinds of recognition to this day. First page > The Scene in Scotland > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White