Scotland's Victory in the Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn was one of the most pivotal clashes in the history of the wars between England and Scotland. It is most commonly described as taking place on June 23, 1314, but that was the first day of conflict. Unlike many battles of the time, the struggle on the Bannock lasted two days.

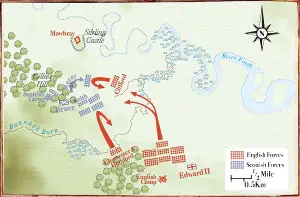

An English army was on yet another expedition north, this time to relieve the siege of Stirling Castle, the only castle not taken by Scottish forces led by Robert the Bruce. Bruce had declared himself King of Scotland, taken the crown, and led his people in a series of guerrilla campaigns dotted by brief moments of victory. England's King Edward II had been preoccupied with an armed uprising for the past few years but was at the head of a full-strength army in 1314, intending to ride to the rescue of the Englishmen stuck inside Stirling Castle. The Scottish army had laid siege to the castle for a few months, and the Englishman in charge of the castle, Sir Philip of Mowbray, had agreed to hand over the castle on June 23 if English reinforcements hadn't arrived. Edward responded by sending the largest ever invasion force in this long struggle between nations: 10,000 infantry and 3,000 heavily armored cavalry. By contrast, in the Scottish force on the field of battle at Bannockburn would be 7,000 infantry and 600 light horsemen. Both sides had a few hundred archers, but neither contingent featured in the fray. Bruce had deployed his forces south of Stirling Castle, where the road went through a royal hunting park known as the new Park.

The first bit of folly was committed by Sir Henry de Bohun. The heavily armored English knight, atop his trusty war steed, was among a group of English cavalry who stumbled on a bit of the Scottish army and realized that Bruce himself was in the group. Bohun charged across the field, intending to strike Bruce down and end the Scottish rebellion. Bruce, armed with an axe and a shield (and no lance), was sitting atop a small, unarmored horse. This meant, however, that Bruce had more maneuverability than Bohun did. Charging hard, Bohun drove his lance hard at Bruce, who parried and then drove his axe through Bohun's skull. It was a bit of foreshadowing for what came next.

Taking a couple pages out of the strategy book of his fellow Scottish patriot William Wallace, Bruce made sure that the English had to contort themselves in order to attack the Scottish deployments. For a start, Edward's forces had to cross the Bannock, a stream ("burn" being Scottish for stream), by means of a narrow ford. Just at Stirling Bridge, the battle that made Wallace famous, the English were forced into a narrow crossing. The English forces who did get across the slight body of water were met with Scottish footmen armed with very long metal-tipped wooden spears and arrayed in close formations known as schiltrons. William Wallace had used a similar tactic at the Battle of Falkirk, although those spears had been driven into the ground and the men holding them had been backed by a second wave of spearmen holding their spears over the heads of the first wave; the result was an effective nullification of the natural advantage of a heavy cavalry charge, the deadliness of the trampling hooves of the horses. Wallace's strategy had worked at Falkirk as far as stopping the cavalry charge, but Edward I's large contingent of longbowmen rained down arrows on the Scots manning the schiltrons and that was the difference in the battle.

Commanding the schiltrons at Bannockburn were the Earl of Moray, Edward Bruce, and Robert the Bruce. For added insurance, Bruce had dug pits in front of the schiltrons and covered the pits with branches, the idea being that such hazards would blunt the effectiveness of a charge by the English heavy cavalry. The combination of the spears and the pits suggested that the Scottish forces were deployed in a purely defensive way. However, these schiltrons were not driven into the ground but were instead held by soldiers who at first held their ground but then advanced on the English vanguard, who then got entangled in the Scottish-dug pits. The resulting surprise led to a period of savagery. The slaughter was evident enough to convince the English to pull back. But they did not leave the field of battle. They did however, have a bleak mood about them, and this was reported to Bruce in the person of Alexander Seton, a Scottish knight who had been fighting with the English but switched sides after seeing the spark of fight in the Scottish army on the first day of battle. Seton urged Bruce to abandon his defensive position and engage the English. Edward ordered another attack the next day, a bit further east, in an attempt to outflank the schiltrons and avoid the pits that had caused such chaos the day before. At some point early in the day, the Scottish forces to a man knelt in prayer. The English response was to attack, and they were surprised again when the Scottish charged as well, brandishing their slight wooden spears against a sea of mounted cavalry. However, the elements favored the Scottish forces again. The ground in that area was boggy, and the first part was surrounded on three sides by water. Again, the English were in a position too narrow in which to take advantage of their superior numbers. The heavily armored knights sitting atop the heavily armored horses sunk in the bog and made easy targets for the suddenly offensive schiltrons, who brandished their long spears in charge after charge (a tactic not employed by Wallace at Falkirk). Some of the English cavalry charged anyway, and some had success; the rest did not and were rendered ineffective.

Edward's secret weapon, a contingent of Welsh bowmen, was not a factor and was, in fact, driven away by a Scottish cavalry charge. The English lines broke, and English foot soldiers and horsemen tried to retreat over the high banks of the Bannock and across to the other side. Many died in the confusion. The heavily armored English found it difficult to move quickly, and many fell prey to Scottish fighters armed only with small daggers. Edward himself was nearly captured, being dragged away just before a Scottish force converged on his position. The Scottish had won the day. The English turned back southward. Stirling Castle surrendered. Bruce took a number of English nobles hostage and exchanged them for his wife and daughter, whom Edward had held captive since 1307. It would be several years yet before Scotland achieved independence finally from England. But the Scottish victory at the Battle of Bannockburn was a giant first step toward that goal. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White