New Spain

Part 2: Settling in, Fighting Wars

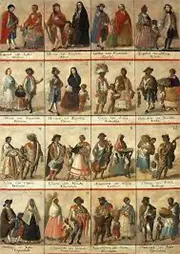

The New World possessions were very far away from Spain, and viceroys enjoyed a large amount of autonomy. The Crown at times sent royal inspectors, some of whom traveled in secret, to check on the doings of a viceroy. From the centralized viceroyalty downward through the various layers of government, the Crown set up a large number of civilian towns (pueblos), military towns (presidios), and religious missions (misiones). Ruling each of the various provinces were administrators known as Corregidores. Socially and politically, the Spanish Crown introduced a four-tier class system into New Spain:

All of that government and bureaucracy had as a primary purpose the expansion of Spanish possessions in the New World and the further accumulation of wealth from those possessions. Conquistadors and others worked to subdue the native peoples, as Cortés and Francisco Pizarro had demonstrated could be done. Spanish forces conquered the Yucatan and then moved northward, having particular trouble subduing the remaining Maya living on the Peninsula. Cities founded during this time and the next few decades included Antequera, Campeche, Colima, Guadalajara, Querétaro, Veracruz, and Zacatecas. One primary benefit to the settlers and original residents of New Spain was that the Spanish Crown placed a premium on education. The settlement of Texcoco in 1523 had the Americas' first primary school and in 1551 had the Americas' first university, the University of Mexico. Furthering the cause of learning was the New World's first printing press, rolling by 1524. All of this settlement and conquest was not without controversy. Employing a combination of determination, ruthlessness, and advanced weaponry, Spanish leaders and soldiers conquered a vast amount of territory, spreading Spanish values, European ways, and Christian practices along the way. A few times, indigenous peoples struck back. One was in 1540 and 1541, when Viceroy Mendoza himself led an army to put down the Mixtón Revolt. Nine years later began the long-lasting Chichimeca war, which went on for more than five decades. A Spanish expedition led by Pánfilo de Nárvaez to Florida in 1528 ended in disaster; only four people of the original 600 survived the shipwreck and straggled into Mexico years later, after surviving a period of captivity in the hands of Native Americans. One of the things that kept these survivors going was the promise of the Seven Cities of Gold that they had heard about along the way. Wave after wave of explorers swept through more and more territory, searching for Cíbola and the other fabled golden cities. The survivors of the Gulf of Mexico shipwreck, led by the nobleman Alvan Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, reached what is now New Mexico in 1527. Marcos de Niza arrived in what is now Arizona in 1539. Among the most well-known of these hopeful explorers was Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (right). He and a group of 1,700 men set out Farther west went the explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, the first European to lead an expedition to explore what is now the west coast of the U.S. In 1542, his three ships and 200 men sailed up the Baja California coast, past what is today San Diego and going as far as what is today Monterey Bay. Two settlements well-known to students of American history are St. Augustine, which Spanish settlers founded in 1565, and Santa Fe, which came about in 1610. Santa Fe was not the first Spanish capital of new Mexico. A 1580s expedition led by Bernardo Beltran and Antonio de Espejo explored much of the area; this expedition is thought to have been the first to use the term la Nueva Mejico. Don Juan de Oñate marched alongside the Rio Grande north in 1598, with a collection of troops and settlers in tow. They settled at the Native American village of Yungueingge and renamed it San Gabriel del Yunque; this became the first Spanish capital of new Mexico. The founding of Santa Fe as capital came as the result of actions by then-Governor Don Pedro de Peralta. A period of Spanish settlement ensued, punctuated by missionary efforts to convert the native peoples to Christianity, as elsewhere. Many of these native peoples didn't take kindly to such encroachment on what had been their homelands, and a large revolt led by Taos Pueblo occurred in 1680, resulting in a Spanish withdrawal south. Just a bit further west, Spain built more permanent settlements, including Tubac in 1752 and Tucson in 1776.

In between that time, Spain, England, France, and other European powers fought the Seven Years War, which had a North American corollary known as the French and Indian War. The North American part of that conflict ran from 1754 to 1763. Great Britain's victory over France resulted in the latter's surrendering all of New France. British troops seized the Spanish trade centers of Havana and Manila, resulting in an increased military presence in other Spanish ports and other cities after that war. And in order to regain Cuba, Spain ceded Florida to Britain. Spain had also gained the Louisiana Territory from France during this time. Next page > High and Lows and the End > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

In 1535, the king established the Viceroyalty, handing over authority to a person in residence. The first of many viceroys was Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco (left). In the three centuries of New World rule, more than 70 served as viceroy; some served for only a few months, and the longest-serving (Mendoza) held the office for 15 years.

In 1535, the king established the Viceroyalty, handing over authority to a person in residence. The first of many viceroys was Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco (left). In the three centuries of New World rule, more than 70 served as viceroy; some served for only a few months, and the longest-serving (Mendoza) held the office for 15 years. Spaniards were the top class, the only ones who could perform government jobs at the highest level. These people born in Spain enjoyed other favors not granted to people of the lower classes.

Spaniards were the top class, the only ones who could perform government jobs at the highest level. These people born in Spain enjoyed other favors not granted to people of the lower classes. from Compostela on Feb. 23, 1540 and went through what is now Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. One contingent, led by Hernando de Alarcón, went via the Guadalupe River; Coronado led the other force, which traveled on land. They all found rumors but nothing more: Cíbola was nothing more than a normal settlement. Most of his force returned to Mexico in 1541; Coronado and a much smaller forced carried on, eventually returning empty-handed in 1542. Coronado claimed for Spain all of the land he explored. It was about the only benefit that his explorations brought.

from Compostela on Feb. 23, 1540 and went through what is now Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. One contingent, led by Hernando de Alarcón, went via the Guadalupe River; Coronado led the other force, which traveled on land. They all found rumors but nothing more: Cíbola was nothing more than a normal settlement. Most of his force returned to Mexico in 1541; Coronado and a much smaller forced carried on, eventually returning empty-handed in 1542. Coronado claimed for Spain all of the land he explored. It was about the only benefit that his explorations brought.