Martin Luther: Religious Revolutionary

Part 2: Reform and Revolution Luther spoke out against this practice a few times in sermons that he delivered in 1517. Especially galling to him was that the money raised from the granting of these indulgences was not staying anywhere near Wittenberg or even Germany. Churches in Luther's town and in his country needed money for repairs, but the money that Rome's Tetzel was generating was going straight back to Rome, to help pay for an expensive repair to an ornate church there.

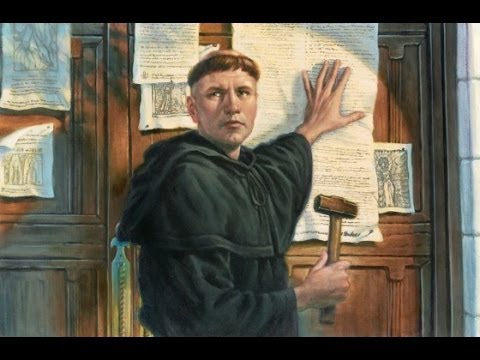

Luther had finally had enough and composed a series of statements that he hoped would stimulate discussion among his colleagues. On Oct. 31, 1517, he wrote to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, in a series of objections to church practices that had the official title of "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences" but became known as the 95 Theses. He also wrote these statements, all 95 of them, on a document and affixed it to the door of All Saints' Church in Wittenberg. This was a common practice at the time; what was not common was challenging the Church so fundamentally. Someone removed Luther's document and copied it into German. (Luther had written in Latin.) The 95 Theses then made their way, in German, into the hands of many people through the advent of the relatively new invention of the printing press. Soon, Luther's thoughts and beliefs on indulgences and other Church matters were common knowledge. Word of the Theses eventually reached other countries, notably England, France, and Italy. The response from the Church was slow in coming but definitive when it came. Luther had, at the time of the posting of the 95 Theses on the door of All Saints' Church, also written to Archbishop Albrecht, anticipating a further discussion on the matters arising from the Theses; Albrecht made no answer. Church officials summoned Luther to Augsburg, where he defended his Theses assertions during three days of intense questioning from papal representative Cardinal Cajetan. The cardinal had been ordered to arrest Luther if he did not recant (take back) his statements, but no arrest was ordered. The following year, Luther was again before a papal representative, this time in Altenburg; among the claims that Luther made during this debate was that neither popes nor church councils were infallible. This was in direct contradiction to established Church doctrine.

Pope Leo X in 1520 issued a papal bull (official statement) asserting the correctness of the Church and ordering Luther to recant everything that he had said or written that went against the teachings of the Church; Luther refused and, in an act of public defiance, burned the papal bull. Early the following year, the pope excommunicated Luther (effectively kicking him out of the Church) and even issued a death warrant; Luther found protection, however, in Wartburg Castle, owned by Prince Frederick of Saxony.

Luther did come out of hiding for a very high-level meeting, the Diet of Worms, on April 17, 1521. The head of the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Charles V, presided over the meeting, a general assembly of all of the various states that made up the Empire. The meeting took place in a city called Worms. In front of these very powerful secular leaders, Luther again refused to recant what he had said or written. The famous quote attributed to him from this meeting is this: "Here I stand. I can do no other." Stunned by Luther's actions, Emperor Charles V issued an edict ordering that Luther's works should be burned. Luther went into hiding again, in the town of Eisenach. While in hiding, he translated the New Testament of the Bible from Greek into German. This proved to be another of Luther's publishing sensations. He also grew a beard and adopted a fake identity, Junker Jörg, at times even discussing "the Luther situation" with other people who didn't recognize him. In 1524, a number of peasants in Germany revolted, citing Luther's pronouncements as provocation for overthrowing Church authority. The revolt turned violent, with outraged peasants smashing idols and other elements inside churches. Some violence included the burning of entire buildings: convents, monasteries, and even libraries. Luther sympathized with the peasants' concerns but condemned the violence. The Peasants' War, as it became known, continued, spreading through much of central Germany. The leaders of the uprising published their own grievances, "The Twelve Articles of the Peasants"; Luther responded with publications of his own.  In the early days of this uprising, Luther had helped nine nuns flee a convent in order to avoid being harmed, by hiding them in barrels of herring that were spirited away under cover of night. Eight of the nuns eventually found safety with families or with new husbands. By the summer of 1525, only Katherina von Bora remained, staying in Wittenberg, at a private house. Luther at this time was in Wittenberg, living alone in what had been the Augustinian monastery because the other monks had fled or renounced their faith. Despite the Catholic Church's prohibition against clerics marrying, Luther married Katherine, on June 13, 1525. By that time, other clerics had married; Luther's wedding, however, was the most high-profile of them all. The Luthers eventually had six children, four of whom lived into adulthood: Hans (1526), Martin (1531), Paul (1533), and Margarete (1534). Katherine also invested in a brewery and farms and orchards, increasing the family's wealth. Just as political leaders had ordered Luther to take back what he had said and written, the movement that came to be called Protestantism was becoming a political movement, with other leaders following in Luther's footsteps in questioning Church doctrine. Luther spent the first few years after his marriage organizing a new church. He devised a new program of worship, including a Mass in German. Adding to his 1522 German-language translation of the Bible's New Testament, he completed a German version of the Old Testament in 1534. He wrote many hymns as well, some of which are still sung today. Luther had harsh words for the Catholic faith and its leaders. He also criticized the two other major Western religions, Islam and Judaism. His words on Jewish people were particularly venomous at times.

He publicly feuded with other well-known intellectuals, including the famous Catholic scholar and philosopher Desiderius Erasmus and his fellow Protestant leader Huldrych Zwingli; at the former he directed his famous pamphlet On the Bondage of the Will, and at the latter he directed a vehement defense of his position on the meaning of the Eucharist. In his later years, Luther suffered from a variety of illnesses, including tinnitus and vertigo. He also contracted Méniêre's disease. He struggled through these as the number of ailments increased. From 1536, he battled arthritis, bladder stones, and kidney stones. These afflictions were not uncommon in medieval times. Beginning in late 1544, he showed symptoms of heart trouble. He delivered a sermon at Eisleben, his birthplace, on Feb. 15, 1546. It was his last. He died early in the morning on February 18, finally succumbing to the after-effects of a stroke. He was 62. His legacy lived on, in the Lutheran religion in particular and in the Protestant Reformation as a whole. First page > Building a Faith > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White