Martin Luther and the 95 Theses

On October 31, 1517, a professor posted a request for an argument on a church door in a small German town. The result was a major religious transformation.

At the time, Luther was on the faculty of the University of Wittenberg, from which he had been awarded a Doctor of Theology degree in 1512. He initially sought study of the law and then philosophy but had switched to religion. Luther was still teaching at the University of Wittenberg four years later, when a Dominican friar named Johann Tetzel arrived in Germany, sent by the Roman Catholic Church to raise money to help rebuild St. Peter's Basilica. One of the prime methods of fund-raising was the granting of indulgences, which were the religious equivalent of a legal plea bargain, whereby the person who paid a sum of money to the Church could then be assured by Church officials that his or her suffering would be lessened because he or she would be absolved of (forgiven for) any sins (actions against the teachings of the Church). The practice of granting indulgences was not a new one. Criticism of the practice was not new, either. Early Church protesters, among them John Wycliffe and Jan Hus, had spoken out against the practice. The main objection to this practice, according to Luther, was that it amounted to the medieval equivalent of a “Get Out of Jail Free” card, after the board game Monopoly. Anyone could, provided that he or she paid enough money to the Church, be told in no uncertain terms that they were forgiven for things that they had done and that the forgiveness came from the Christian God. People like Tetzel and others were speaking on behalf of the Pope, who claimed divine authority to be God's witness on Earth. What troubled Wycliffe, Hus, and Luther about this practice of granting indulgences was that it eliminated the need for a person to change his or her life or behavior in order to seek forgiveness; on the contrary, all that was needed to guarantee absolution was to open one's purse. Luther spoke out against this practice a few times in sermons that he delivered in 1517. Especially galling to him was that the money raised from the granting of these indulgences was not staying anywhere near Wittenberg or even Germany. Churches in Luther's town and in his country needed money for repairs, but the money that Rome's Tetzel was generating was going straight back to Rome, to help pay for an expensive repair to an ornate church there.

Someone removed Luther's document and copied it into German. (Luther had written in Latin.) The 95 Theses then made their way, in German, into the hands of many people through the advent of the relatively new invention of the printing press. Soon, Luther's thoughts and beliefs on indulgences and other Church matters were common knowledge. Word of the Theses eventually reached other countries, notably England, France, and Italy. The response from the Church was slow in coming but definitive when it came. Luther had, at the time of the posting of the 95 Theses on the door of All Saints' Church, also written to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz and Magdebury, anticipating a further discussion on the matters arising from the Theses; Albrecht made no answer. Church officials summoned Luther to Augsburg, where he defended his Theses assertions during three days of intense questioning from papal representative Cardinal Cajetan. The cardinal had been ordered to arrest Luther if he did not recant (take back) his statements, but no arrest was ordered. The following year, Luther was again before a papal representative, this time in Altenburg; among the claims that Luther made during this debate was that neither popes nor church councils were infallible. This was in direct contradiction to established Church doctrine. Pope Leo X in 1520 issued a papal bull (official statement) asserting the correctness of the Church and ordering Luther to recant everything that he had said or written that went against the teachings of the Church; Luther refused. Early the following year, the pope excommunicated Luther (effectively kicking him out of the Church) and even issued a death warrant; Luther found protection, however, in a castle owned by Prince Frederick of Saxony. Luther did come out of hiding for a very high-level meeting, the Diet of Worms, on April 17, 1521. The head of the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Charles V, presided over the meeting, a general assembly of all of the various states that made up the Empire. The meeting took place in a city called Worms. In front of these very powerful secular leaders, Luther again refused to recant what he had said or written. The famous quote attributed to him from this meeting is this: "Here I stand. I can do no other." Stunned by Luther's actions, Emperor Charles V issued an edict ordering that Luther's works should be burned. Luther went into hiding again, in the town of Eisenach. While in hiding, he translated the Bible from Latin into German. This German-language Bible proved to be another of Luther's publishing sensations. Just as political leaders had ordered Luther to take back what he had said and written, the movement that came to be called Protestantism was becoming a political movement, with other leaders following in Luther's footsteps in questioning Church doctrine. By the time that Luther died, in 1546, the Protestant Reformation was well under way. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

The professor was

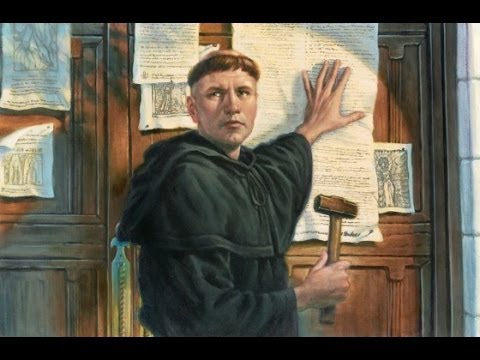

The professor was  Luther had finally had enough and composed a series of statements that he hoped would stimulate discussion among his colleagues. He wrote these statements, 95 in all, on a document and affixed it to the door of All Saints' Church. This was a common practice at the time; what was not common was challenging the Church so fundamentally.

Luther had finally had enough and composed a series of statements that he hoped would stimulate discussion among his colleagues. He wrote these statements, 95 in all, on a document and affixed it to the door of All Saints' Church. This was a common practice at the time; what was not common was challenging the Church so fundamentally.