The Kingdom of Holland

The Kingdom of Holland was a short-lived monarchy in the early 19th Century. The list of people who held the title of King of Holland is very short.

The economic and political fortunes of the Netherlands had risen and fallen with a nominally representative government in the form of the States-General. In truth, the stadtholder of the House of Orange (mostly a series of Williams) was the real head of the government. All of that changed in the 17th Century, when the Dutch Golden Age was waning and the Dutch economy was struggling. William V proved too authoritarian for the Enlightenment-drive Dutch Patriots, a group that included many of the nobility. The success of the French Revolution encouraged Dutch protesters to go further, and they rose up in revolution against their government, in 1795. Taking their name from an ancient Germanic tribe that resisted the mighty Roman Empire, they declared the Batavian Revolution. Sealing their success was a once-in-a-lifetime success by an invading French army, crossing the suddenly frozen solid rivers that had traditionally made the Netherlands immune from attack. The government, officially overthrown, became the Batavian Republic.

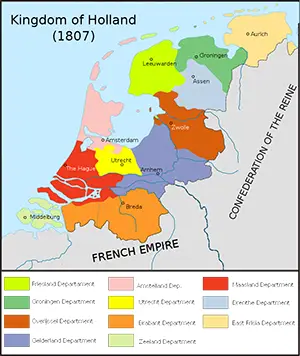

Unable to resist, radicals and reactionaries took turns enacting coups, ruling on their own for a bit until replaced by another overthrow. The Batavian Republic was little more than a client state to France, which by this time was a military and political powerhouse. The French ruler, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, made two changes in leadership, replacing the representative structure of the republic with a one-man show, first in the form of former Dutch Ambassador to France Rutger Jan Schimmelpenninck and then in the form of Bonaparte's own brother Louis. On June 5, 1806, Louis Bonaparte became King of Holland. The newly created constitutional monarchy had 11 Departments: Amstelland, Brabant, Drenthe, East Frisia, Friesland, Gelderland, Groningen, Maasland, Overijssel, Utrecht, and Zeeland. King Louis I was the head of government; assisting him were ministers and advisers.

Louis had played a role in his older brother's successes, and he understood that he was to be a ruler who nonetheless took orders from another. However, Louis developed an affinity for the people he ruled, styling himself King Lodewijk, attempting to learning the Dutch language and requiring his ministers and advisers to speak it and not French. When Napoleon, gearing up for an invasion of Russia, called for Louis to institute military conscription, the younger Bonaparte refused. Skating on thin ice, Louis persevered, refusing to combat smuggling, to which many of his citizens had resorted as a means to overcome the depressed economy affected in part by Napoleon's Continental System. The French response was to deploy forces of customs inspectors throughout the Dutch countryside. When U.K. troops invaded Walcheren in 1809 and Louis refused to send in a defense, Napoleon had had enough. On July 1, 1810, Louis abdicated his throne, in the wake of France's Louis had married Hortense de Beauharnais in 1802. They had three children together: Napoleon-Charles, Napoleon-Louis, and Napoleon III. The oldest son died in 1807. When Louis relinquished his throne, his second son, Napoleon-Louis, became king. All of 6, he ruled as Lodewijk II (with his mother as regent) for all of 12 days before the French annexation was official and the Kingdom of Holland was no more. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

annexation of the kingdom.

annexation of the kingdom.