The Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War, won decisively by Prussia in just over six months, shifted the balance of power in continental Europe in favor of the German states, which were united during the war. Germany as its is known today was not a united country for much of the 19th Century. Although much of the area had been part of the Confederation of the Rhine (a collection of territories put together by Napoleon Bonaparte), the Congress of Vienna (an 1815 gathering of the European powers in the wake of Napoleon's final defeat) resulted in a large number of independent German kingdoms. The largest and most powerful of these kingdoms was Prussia, led by its powerful and dynamic chancellor, Otto von Bismarck.

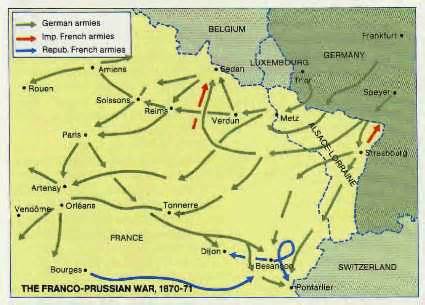

At the same time, the throne of Spain was vacant and the man named to be the new king was Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a Prussian prince. (The Spanish throne had been empty since a revolution in 1868 had end the long reign of the Bourbons.) Emperor Napoleon III of France loudly declared his opposition to having Prussian rulers on France's western and eastern borders, and Spain agreed to find another king. The French ruler insisted that his Prussian counterpart, Wilhelm I, apologize via a state telegram. Wilhelm I agreed to do this, but Bismarck edited the telegraph to read as if it were extremely insulting to France and sent it on, hoping to use it as a pretext for war between France and Prussia. French Emperor Napoleon III, wary of the expansionary interests of Bismarck and Prussia while also wanting to reclaim some of the glory of his namesake, was also looking for a pretext for war with Prussia; and after consulting with his generals (who assured him of a French victory on the battlefield, should it come to that), took the opportunity to be extremely insulted by the telegram (known as the Ems Dispatch) and urged the French parliament to declare war on Prussia. Parliament agreed, on July 16, 1870, and war began three days later. The French military was confident that aid would come from not only Austria, which had only just fought a war with Prussia, but also a few of the southern German kingdoms wary of Prussian influence. But Austria chose to stay out of the war and the southern German kingdoms sided with Prussia. In a precursor to the entire shape of the war, Prussia proved much more adept at mobilizing its troops and had sent more than 450,000 men on an invasion force that got itself into northeastern France before Napoleon III's government could mobilize its force, which consisted of just more than 270,000. The southern German kingdoms had sided with Prussia, giving Bismarck and Wilhelm and company much-needed support in manpower, money, weapons, and railroads. The latter proved especially important in Prussia's ability to move men and supplies rapidly from one place to place, seemingly at a moment's notice.

Peace negotiations dragged on, and the Treaty of Frankfurt was signed on May 10, 1871. As a result, France had to pay a huge sum of money and give up some prime territory, including the oft-fought-over areas of Alsace and (most of) Lorraine. German troops also remained in France in significant numbers until the reparations had been delivered in full, two years later. If France was worried about Prussian influence before the war, then French worries would have been greatly increased after the war, especially since Prussia had become the power behind a much larger, united German nation. The unification of Italy in the same year eventually led Austria, recently converted into the Dual Monarchy of Austria and Hungary, covet a similar unification of disparate territories and peoples. Great Britain and Russia as well would eventually react with wariness to the unifications. The result was a criss-crossing series of alliances (most notably the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente), and strict adherence to those alliances in part led to the start of World War I. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White

Prussia had taken just seven weeks to defeat Austria in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War (also called the Seven Weeks' War). After the victory, Prussia had seized control of several surrounding territories and, uniting with several northern German kingdoms, declared the creation of the North German Confederation. Prussian Chancellor Bismarck set to work creating a united Germany by courting the southern German kingdoms of Baden, Bavaria, Hesse-Darmstadt, and Wurttemberg.

Prussia had taken just seven weeks to defeat Austria in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War (also called the Seven Weeks' War). After the victory, Prussia had seized control of several surrounding territories and, uniting with several northern German kingdoms, declared the creation of the North German Confederation. Prussian Chancellor Bismarck set to work creating a united Germany by courting the southern German kingdoms of Baden, Bavaria, Hesse-Darmstadt, and Wurttemberg. Despite deploying two technological advances in weaponry, the Chassepot rifle and the mitrailleuse (an early version of a machine gun), the French were outnumbered, outgunned, and out-mobilized. In addition, the Prussian practices of universal conscription (draft) and a full-time central military command proved decisive in many of the swift Prussian victories (Spicheren, Worth, Gravelotte, Mars-La-Tour, and Metz) that made up the war. Napoleon III himself was captured, at the Battle of Sedan, on September 2. Although the war continued, the empire did not, as revolutionary elements in Paris declared the Third Republic. German troops advanced all the way to Paris and lay siege to the city. On January 28, 1871, German troops seized control of France. Not long after, the German states declared themselves united, with Wilhelm I as their Kaiser. France, meanwhile, overthrew the revolutionary government (known as the Paris Commune).

Despite deploying two technological advances in weaponry, the Chassepot rifle and the mitrailleuse (an early version of a machine gun), the French were outnumbered, outgunned, and out-mobilized. In addition, the Prussian practices of universal conscription (draft) and a full-time central military command proved decisive in many of the swift Prussian victories (Spicheren, Worth, Gravelotte, Mars-La-Tour, and Metz) that made up the war. Napoleon III himself was captured, at the Battle of Sedan, on September 2. Although the war continued, the empire did not, as revolutionary elements in Paris declared the Third Republic. German troops advanced all the way to Paris and lay siege to the city. On January 28, 1871, German troops seized control of France. Not long after, the German states declared themselves united, with Wilhelm I as their Kaiser. France, meanwhile, overthrew the revolutionary government (known as the Paris Commune).