Napoleon III: France's Last Monarch

Part 1: Rise to Power Napoleon III was the last monarch of France. A nephew of the famous Napoleon Bonaparte, he ruled France as President, Prince-President, and then Emperor, from 1848 to 1871.

He was born on April 20, 1808 in Paris. His name at birth was Charles-Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. His father was Louis Bonaparte, who ruled Holland in 1806–1810; his mother was Hortense Bonaparte, whose mother was Josephine Bonaparte, who at the time was Empress of France, married to Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. When Napoleon abdicated for the second time, in 1815, and was exiled to St. Helena, his family fled France. Young Louis-Napoléon grew up in Switzerland and went to school in Augsburg, Germany. He went with his mother to Rome in 1823 and set about learning Italian and studying ancient ruins. Louis-Napoléon had an older brother, Napoleon-Louis, and the two were in Italy together at the same time. In 1831, they joined the Carbonari, a secret society dedicated to ousting Austria from its overlordship of Italy. They became wanted by Austrian authorities and fled to France, arriving during the reign of Louis Philippe. Napoleon-Louis died of measles, but the surviving brother soon enjoyed the company of his mother, newly escaped to France as well. Mother and son met with the king, who agreed that Louis-Napoléon could serve in the French Army as long as he changed his name. He refused, and the king ordered them out of Paris. They left France entirely, heading to the United Kingdom and then back to Switzerland. While there, Louis-Napoléon joined the Swiss Army and wrote a manual on artillery.

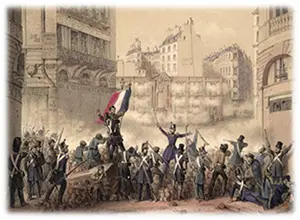

Napoleon's son, known as Napoleon II, died in 1832. Louis-Napoléon envisioned repeating his uncle's famous march to Paris during the Hundred Days and engineered an uprising in Strasbourg that he hoped would spread. This was not successful, and he fled Europe, traveling to Brazil and then the U.S. before returning to Switzerland to be with his mother in her last days. He was not allowed back in France, however, and so returned to London. He tried again to convince the French people to rebel against the king, in 1840. That uprising attempt was even less successful than the first one, and he was captured and imprisoned. After six years in prison, during which he kept up on the resurgent popularity of his famous uncle, he escaped and returned to London. A history student in school, he studied at the British Museum. He mingled with the upper echelons of U.K. society, meeting the author Charles Dickens and the on-again-off-again prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. Not long after he had escaped, his father died. This made Louis-Napoléon the heir to the imperial throne that his famous uncle had vacated in 1815. He was keenly aware of the political distress that King Louis-Philippe was under 1848, the year that revolutions consumed several countries in Europe. It wasn't just poor people in France who rose up in 1848. Doctors, lawyers, merchants, and other members of the middle class took place in public campaigns for an increase in opportunities both economic and political. Leaders of this movement put on banquets at which they made speeches in favor of the kinds of the change that they were seeking, in hopes of gaining donations to their cause. One of the things that most people in France wanted at this time was the right to vote. By 1848, only 1 percent of the population could vote, and a majority of people thought that it was time to enact legislation to provide it for the rest. The banquets became quite popular and attracted a large number of people. On Feb. 22, 1848, officials in Paris canceled a scheduled banquet because they feared that the banquet would turn into an organized protest. The cancellation of the banquet did just that, as a crowd descended on the streets of the capital, forming barricades and taking up arms to press their case for reform. Joining them were the citizen-manned militia the National Guard and an army garrison stationed in Paris. Prime Minister Francois Guizot resigned, but it was not enough for the crowds. King Louis Philippe was unable to impress his subjects with enough of a set of reforms and ended up fleeing his throne, going into exile in the United Kingdom. On February 26, the protesters organized a provisional government, the Second Republic, and set about making change. One of the first acts of the new government was the granting of universal (for men) suffrage; at a stroke were created 9 million new voters. Not long afterward, a new government was in place. Heading up the provisional government was an Executive Commission, formed by five co-presidents; the new legislative body was the National Constituent Assembly.

The other main goal of this new government, unemployment relief, proved more problematic. On May 15, a large group of workmen stormed the Assembly and announced the creation of yet another new government. This revolt did not have the support of the National Guard, and the leaders were arrested and later tried. Two weeks later, fed up with the lack of a quick solution, a few thousand Parisians rioted. Further clashes between protesters and security forces took place in June, with more seizures of parts of the city and more protesters armed and standing behind barricades in what came to be known as the June Days uprising. Even with a force of more than 120,000, it still took the army two days to clear the streets. Things settled down considerably after that, but tensions were still high in some parts of the capital and in the country as a whole. A new election in December saw the election of one president, to take the place of the committee of five. The winner of that election was Louis-Napoléon. Next page > Enacting Wide-ranging Change > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White