The Napoleonic Code

The Napoleonic Code was a landmark set of laws adopted by France in the early 19th Century. France did not have a single set of laws. Rather, local custom ruled some matters and kingly conventions ruled others. Much of southern France followed legal conventions from Roman times. In the north, legal customs came from the Frankish tradition. Monarchs handed out privileges and exemptions based on personal preference or whims. The Catholic Church set precedents for marriage and family matters that were seen as laws. More recently, a series of parlements had made decisions regarded as legal precedents. In addition, the French Revolution had brought about the abolition of the feudal system and a widespread discontent with the Ancien Régime and its stratified society based on economic class.

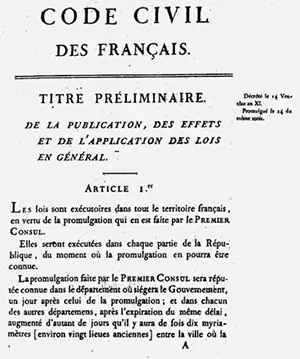

A committee of four well-known judges crafted the Code, using the rule of reason as their guiding light. A unanimous resolution of the National Constituent Assembly on Sept. 4, 1791, had called for "a code of civil laws common for the entire realm." Doing the initial drafting was Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, who served as Minister of Justice and, under the Consulate, as Second Consul. Cambacérès had been working on initial versions of the Code since 1793; the Assembly rejected the first several drafts as too technical. The establishment of the Consulate in 1799 brought with it a four-judge panel (one of whom was Cambacérès) to finish the work. First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte (left) chaired nearly half of the committee's more than 80 meetings. The judges finished their work, then turned it over to the Council of State for review. The final laws, a series of 36 statues, were enacted progressively, from 1801 to 1803. Bonaparte announced the implementation of the wholistic Code on March 21, 1804. Its initial title was Code civil des Français. The name Code Napoléon (Napoleonic Code) came in 1807. Among the prohibitions of the Code were these:

However, the Code also solidified the man (husband or father) as head of the household, reversing the "equality for all" philosophy of the Revolution. Also reversing a principle set out explicitly in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the Code made slavery in French colonies legal again. The Code took the form of a handful of Books. The 11 sections in the first Book detail laws that dealt with people: marriage and divorce laws, civil rights laws, etc. The laws in the second Book's four sections dealt with things, like property. The third Book's 20 sections of laws dealt with inheritance and other rights. When the Code civil des Français came into being, Bonaparte declared it in effect for not only all of France proper but also other cities, countries, and lands controlled by France, including Belgium, Geneva, Luxembourg, Monaco, and parts of Germany and Italy. As the French Empire conquered more land during the Napoleonic Wars, the Empire extended the Code's provisions to those areas conquered. Following the Civil Code were other Codes:

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

laws passed in secret

laws passed in secret