The Ancien Régime

The Ancien Régime was a political and social system of dividing people by economic class used in France for several centuries, ending with the French Revolution.

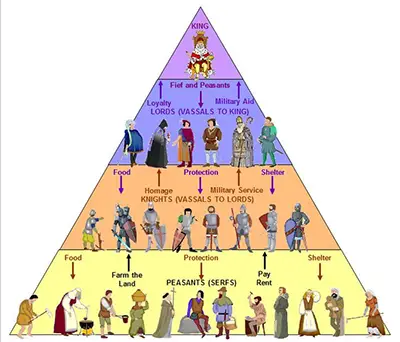

Making up the First Estate were the clergy, the religious leaders of the realm. Nobles and royals excluding the monarch made up the Second Estate. Those two Estates together made up about 2 percent of the population for much of this period. The rest of the population comprised the Third Estate. This included not only commoners and peasants but also slightly wealthier people like businessmen who had respectable and sometimes large incomes. This division into Estates came in handy when the king needed to summon the people for advice, as in the use of the Estates-General. King Philip IV in 1302 called the first Estates-General in order to discuss his power struggle with Pope Boniface VIII. Members of the judiciary and of the Conseil de Roi (King's Counsel) came from the nobility and sometimes the clergy but almost never from the Third Estate. This was another class divide operating in medieval France (and, indeed, in most other countries). One of the other key divides between the Third Estate and the other two was that the former paid the majority of the taxes within the realm. The clergy who made up the First Estate were often exempt from paying taxes because of their status as religious officials. The nobles who made up the Second Estate often gave money and support to the king and could provide men at arms and benefits of land ownership that were intangible benefits to the Crown. The members of the Third Estate could provide labor and tax money. The oldest tax in France was the taille, a direct land tax that was determined based on how land a person held. Clergy and nobles were exempt. Another such tax was the corvée royale, which allowed the Crown to "request" from every able-bodied person a number of days of "free" labor every year. The target of this labor was most often roads, but the Crown found other uses for it as well. Naturally, the Third Estate were the only ones subject to this indirect tax.

One of the more unpopular taxes in French history was the gabelle, a tax on salt. It began as a tax on other things, like wheat and spices and wine. But monarchs in the 14th Century decided that it applied exclusively to salt. Food preservation for most of recorded history made use of salt, to help slow retardation of meat, especially. People also used salt to make cheese and as a cooking aid, and they used salt in feeding their livestock, without which most people in medieval times would have struggled. King Louis IX in 1259 introduced the gabelle on salt and envisioned it as a temporary tax. Philip VI less than a century later had other ideas, the tax became the permanent Pays de grandes gabelles. Further, the Crown forced people to buy a certain amount of salt every year, whether they used it or not. The kings of France increased and decreased their reliance on taxation, depending on need. In times of warfare, taxation could be quite high. This was certainly true during the Hundred Years War and was true to a lesser extent during a handful of subsequent wars.

The French Revolution rejection of the unfairness of the Ancien Régime had as much to do with one king in particular as it did with the spreading of the Enlightenment ideas of equality and individualism found in the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, and other philosophes. That one king was Louis XIV. The Sun King famously proclaimed that he was the state and declared personal rule in his later reign. He also oversaw the prosecution of a number of expensive wars, all of which drained the royal treasury even though it was being supplemented with increases in taxation across the board. Louis XIV died early in the century in which the French Revolution occurred. His ideas of absolute monarchy enthused his two successors, the latter of which bore the brunt of the French people's pent-up discontent. Louis XVI summoned the Estates-General in 1788, in hopes of gaining approval for more taxation. What he got instead was a rejection of the Ancien Régime itself, courtesy of a declaration by the National Assembly that the Three Estates were no longer in existence. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White