The Belgian Revolution

The Belgian Revolution was the culmination of the airing of a number of longstanding grievances, resulting in violent protests that created a new country from the southern part of the Netherlands in the 19th Century.

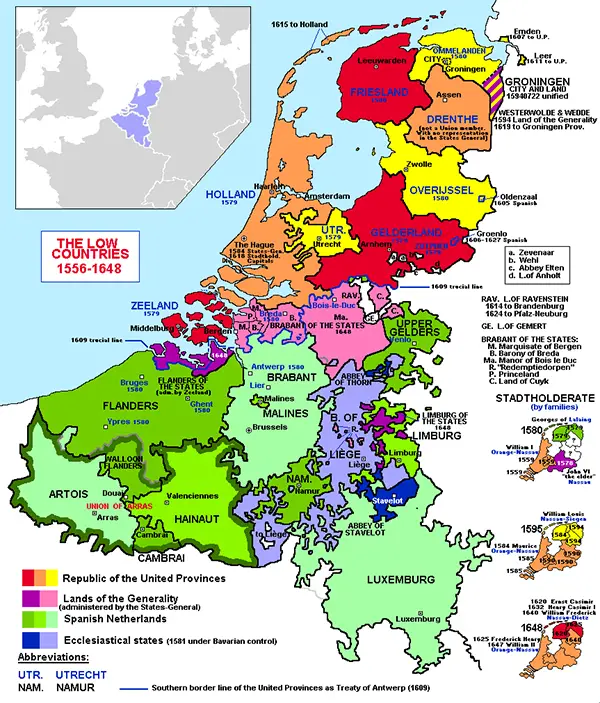

What is now Belgium was part of the Netherlands, the Low Countries, and other such named entities that encompassed a number of cities, provinces, states, and territories in northern Europe. The people in these lands had a long shared history and culture, dating to Celtic and Roman times; however, in the Middle Ages, people began to emphasize their differences–in religious preference, in industrial provenance, and in political sympathy. All of the Low Countries were primarily Roman Catholic for many centuries; the advent of the Reformation and the Protestant movement created a nominal territorial divide that saw the southern provinces remain predominantly Catholic while the northern provinces became a haven for practicers of many types of Christianity and other religions as well. Another division that had geographical causes was the proximity of the southern provinces to neighboring France. The Franks, Carolingians, and Holy Roman Empire had ruled over all of the Low Countries, introducing French and German as official languages along the way. Dutch grew in usage in both north and south but was much more preferred in the north and, in some cases, was the state language. (Naturally, that didn't sit well with the large number of French speakers in the south.) As well, in the 19th Century United Kingdom of the Netherlands, representation was skewed mainly (and sometimes heavily) toward the north. Even though the south had a higher population, the northern interests were more widely and populously represented in government. Conversely, debts incurred by the north were repaid by the central government, to which all citizens paid to help eradicate those debts. It was King William I (left) who accelerated this exacerbation by prioritizing the Dutch language and most things north at the expense of southern interests. Another source of strife was the discrepancy between militia recruitment rates and officer distribution. On average, more from the south were recruited into the militia and more from the north were officers. As well, by the 1820s, the official language of the Dutch Army was Dutch, and so those who spoke mainly French or another more southern language had to learn Dutch in order to serve in the army. Dutch armies had fought against France in the War of the First Coalition. King William I had fought against France, in several significant battles. Unsurprisingly, the southern provinces sympathized with their neighbor France. In the same year that France found its final defeat, at Waterloo, William I took the throne of a new kingdom. This was the birth of the modern country.

In his first capacity as ruler, he had nearly absolute power. His ministers reported only to him, and the States-General had very limited ability to effect change. The following year, he added the title Grand Duke of Luxembourg, gaining rule of that tiny entity after executing a land swap with Prussia. The States-General when William was Sovereign Prince was unicameral. The new kingdom declared a two-chamber body, whose prime responsibility was to approve the laws and decrees of the king. This new governmental blueprint proved popular in the north but not so much in the south. In an attempt to offset this, he declared that his inauguration would be in the southern city of Brussels. Among his new initiatives were the creation of a central bank and of a central trading society. William issued a few decrees that angered those in the south, such as requirements for all students to use the Dutch language in schools and to study the teachings of the (Protestant) Dutch Reformed Church. He also nationalized some of the major universities. People in the south by 1830 had had enough. Speaking out against the king and his policies led to increasingly violent confrontations, and riots ensued. An angry William sent armed troops to quell the riots. This action was entirely unsuccessful. In fact, those doing the uprising maintained the upper hand and ultimately declared their independence. In France in that year, a popular uprising against an unpopular monarch, Charles X, had resulted in the king's increasingly autocratic attempts to hold on to power, followed by the success of a large group of protesters at forcing the king to flee. Faced with the angry voices of tens of thousands, Charles X abdicated his throne. In France, this is the July Revolution.

The very next month, similar events took place in Brussels. On August 25, an uprising coincided with the performance of the opera La Muette de Portici, by Auber. Although the show was intended to honor the birthday of the Dutch king, the subject matter of the opera was, in fact, an uprising against a foreign power, in this case Neapolitans rising up against Spain in the 17th Century. Fresh from seeing such a call to arms, a large number of people rushed into the streets of Brussels and joined what was already a growing protest against the king. Protesters seized government buildings and made known their displeasure with the monarch, his authoritarian ways, and his northern favoritism. The protest movement had a rallying cry and a symbol, a newly created flag. The movement also had a target: remove the influence of the king from their lives. The crown prince, also named William, met with town leaders in Brussels; he also met with leaders of the States-General, who informed him that the only way to stop the protests was to sunder the union. The king refused, instead sending in troops. Fighting in the streets solved nothing, and the government troops left the city. The subsequent bombardment of the town by the head of forces in Antwerp removed any lingering goodwill that the troops withdrawal might have created. Leaders of the protest movement set up a Provisional Government and then, on October 4, issued a Declaration of Independence. In November, a National Congress emerged, with the goal of creating a new constitution. The result of that was the Belgian Constituion, proclaimed on Feb. 7, 1831. The intended form of government was a constitutional monarchy. In the intervening months, other European powers got involved. In late December, leaders of Austria, France, Prussia, Russia, and the United Kingdom gathered in December, in the London Conference of 1830. Unsurprisingly, France supported an independent Belgium. The other powers, however, wanted the Low Countries to stay united. Days of discussions resulted in no firm prohibition and so the nascent Belgian state remained. The search for a monarch culminated in the naming of Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, who took the kingly oath on July 21, 1831, and then got on with the business of governing.

King William had no intention of accepting the direction of other European powers in this matter and so sent in more troops to gain Belgium back. A Dutch force of 50,000 under Crown Prince William invaded Belgium on August 2, 1831, and had their way with a Belgian defense force half its size for more than a week, in the Ten Days' Campaign. Among the Dutch successes were the seizure of Leuven and, more importantly, Antwerp. The Belgian king, Leopold I, himself commanding an army, appealed for international support. A French army arrived as reinforcements, and the Dutch invasion force retreated, from everywhere but Antwerp. The Dutch army was in the citadel at Antwerp and, determined to take the city, shelled it. The same French army returned and this time took action, besieging the Dutch army in the Antwerp citadel. The Dutch commander surrendered in late December 1832. Although foreign powers had forced the Dutch king to agree to a truce and then a treaty, William maintained his desire for reunification, supporting various actions for a number of years more. It wasn't until 1839, and another Treaty of London, that William recognized Belgian independence. The final contents were Antwerp, Brabant, Hainaut, Liége, Namur, and East and West Flanders. The city of Maastricht remained Dutch. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White