The July Revolution of 1830 in France

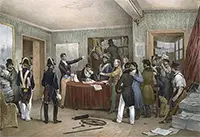

The July Revolution of 1830 in France resulted in the overthrow of an autocratic and unpopular king, Charles X, and the installation of a constitutional monarch, Louis Philippe, who had the support of the people.

The French Revolution had introduced into French society new ideas of equality and tolerance, and those did not go away even as France became an empire under Napoleon Bonaparte. When the younger brother of the executed King Louis XVI (left) took the throne in the Bourbon Restoration, in 1814, he embarked on a rule that sought legitimacy from both rich and poor, noble and commoner. Louis XVIII had varying degrees of success in this regard, but he didn't pass on this desire for tolerance to his younger brother, who became King Charles X when Louis XVIII died, in 1824. Charles had spent most of the years of the Revolution and the Napoleonic Era outside France, living in other European countries. He and his older brother were in Koblenz at the same time, plotting a restoration invasion of France that never happened, and also in the United Kingdom at the same time. The brothers took control of France when Napoleon abdicated, in March 1814. Louis declared himself King Louis XVIII, and Charles was Lieutenant General of the Kingdom. When Louis was firmly on the throne, he sought to pursue a middle course, preserving many of the liberties won by the Revolution while also satisfying many of the concerns of the royalists, many of whom had been disenfranchised, forced to leave the country, and/or relieved of their personal fortunes. He ran into increasingly fierce opposition to this from a large group known as the ultra-royalists, who wanted a return to the days of the absolute monarch. When Charles ascended the throne, he listened to them more and more.

He chose the ceremony of consecration in the Cathedral of Reims, echoing the practice followed by the earliest of the French monarchs and signalling that he was to be a much more autocratic ruler than his brother had been. Among the initial legislation implemented by Charles through Prime Minister Jean-Baptiste de Villéle was a payment to nobles who had lost their lands to the Revolution. Despite support from a number of rich nobles, Charles found himself increasingly out of favor with the rest of the population. Parliamentary elections in 1827 resulted in a majority opposed to the king's plans. He went through a series of prime ministers as well, the last one being Jules de Polignac, who kept Parlement on the sidelines until March 1830. By that time, French troops had occupied Algiers, the capital of Algeria, as part of a military expedition there that was ostensibly to end the threat of Mediterranean piracy but was also intended to evoke former glories through foreign conquest. As well in France as the 19th Century progressed rose a nascent industrial revolution. Mechanization replaced human hands in several industries, putting people out of work. A series of terrible grain harvests in the late 1820s exacerbated the problem for many people who lived hand-to-mouth. Charles had also enacted a law that proscribed the death penalty for acts of sacrilege performed in churches; this was part of an evolving strategy to reinstate the Catholic Church as the preeminent religious force in France. The leaders of the Revolution had downplayed religion as a whole and diminished the A mere three weeks into the new parliamentary session, the king called for elections, which resulted in a large number of people opposed to the king and his policies and actions. In the ensuing elections, in June, a majority were again in opposition to what the king wanted. On July 6, Charles suspended the constitution. On July 25, he issued the Saint-Cloud Ordinances. Among the occurrences that resulted:

One newspaper that was exempt from punishment was the government's own mouthpiece, Le Moniteur, which printed the four ordinances on July 26. Publishers of other papers, the ones who would be targeted by the new ordinance, resolved to protest vehemently, and some called for a revolt. The following day, the newspaper publishers kept their word and went back to work. Police swarmed the offices of some of the newspapers, in an attempt to take hold of the presses; a large group of protesters forced them to abandon those efforts. As well, the streets swelled with protesters, armed with rocks, bottles, and whatever else they had to hand. They formed barricades and resolved to stay until their demands were met. Three actions taken by the king a few years earlier came back to haunt him in these four days at the end of July. The conquest of Algeria was so recent that most of the army was there, in Algeria, and unable to be called on to put down such riots. As well, the king had disbanded the National Guard in 1827, after a One soldier who wasn't in Algeria was Gen. Auguste de Marmont. Charles sent Marmont and a small force of soldiers into the streets of Paris, but they were badly outnumbered, in both men and weapons, and were ineffectual. The protesters took control of the Hôtel de Ville, the town hall and center of the city's government, and rang the bell of Paris.

Another element of the July Revolution was the readoption of the tricolor flag. The blue-white-red flag had been a symbol of France for many years. When Louis XVIII took the throne, he replaced it with a solid white flag. The July 1830 protesters again waved the tricolor flag. By July 29, 30,000 people stood behind 4,000 barricades in Paris. The king refused to talk to the protesters, and Marmont got no reinforcements. The Swiss Guard surrendered the Louvre without a fight, and the protesters seized the Tuileries Palace as well. The calls for Charles to go were not confined to Paris. Protests took place elsewhere; all had the same result. Charles abdicated the throne on Aug. 2, 1830. Taking the throne on August 9 was the people's choice, Louis Philippe, a distant cousin to Charles X. The new leader proclaimed himself King of the French, embraced the tricolor flag, and agreed to be ruled by a constitution. Charles, meanwhile, left France altogether, landing back in the U.K. He did not return. (He died in what is now Slovenia in 1836.) A newly minted constitution was known as the Charter of 1830. Among the provisions of this new governing framework were these:

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

power, wealth, and holdings of the Church. Napoleon had restored Catholicism to favor with the

power, wealth, and holdings of the Church. Napoleon had restored Catholicism to favor with the  number of them had professed opposition to the king and his policies; Charles had not, however, taken the weapons from those members of the National Guard. As the street protests grew, more and more of the weapons formerly wielded by the former members of the National Guard found their way into the hands of the protesters on the street; indeed, many ex-Guardsmen joined in the rebellion.

number of them had professed opposition to the king and his policies; Charles had not, however, taken the weapons from those members of the National Guard. As the street protests grew, more and more of the weapons formerly wielded by the former members of the National Guard found their way into the hands of the protesters on the street; indeed, many ex-Guardsmen joined in the rebellion.