William Lloyd Garrison: Fiery Abolitionist

One of the most prominent abolitionists in America was William Lloyd Garrison, an influential newspaper publisher who crusaded to see the end of slavery and lived to see that end. Garrison was born on Dec. 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Mass. His father, Abijah, a merchant sailor, left the family when William was 3. His mother struggled to rear her three children alone, and William went to live for a time with an acquaintance, who gave him something of an education. He found meager work, selling candy and delivering wood. He returned to live with his mother when he was 11 and went to work as an apprentice to a shoemaker. That job and a subsequent one, learning cabinetmaking, proved too physical demanding.

Garrison discovered the skill that would make him famous when he was 13. In 1818, he gained an apprenticeship to Ephraim W. Allen, the editor of the Newburyport newspaper, the Herald. Garrison served in various capacities for the next seven years and then, age 20, borrowed money from Allen to buy his own newspaper, the Newburyport Essex Courant, which he renamed the Newburyport Free Press. In his newspaper, Garrison advocated a set of political beliefs strongly aligned with those of the Federalist Party, one of America's earliest political parties that had, by this time, faded almost into obscurity. Garrison found that his readers didn't much like the political bent of the Free Press, and Garrison had to close it down just six months after buying it. Garrison soon found another newspaper to work at, the National Philanthropist, in Boston. At the same time, he became involved in the temperance movement, which spoke out against the consumption of alcohol. Three years later, in 1828, Garrison met Benjamin Lundy, a crusading reformer who championed the abolition of slavery through his own newspaper, the Genius of Universal Emancipation. Lundy was impressed by Garrison and walked the 125 miles from his home in Baltimore to Boston to offer Garrison the job as editor of the Genius. Garrison said yes and moved to Baltimore to work with Lundy. He was firmly in the abolition movement. One offshoot of the drive to eliminate slavery was the idea, championed by both blacks and whites, that African-Americans should move back to Africa, to somewhere on the west coast, to regain their heritage. The American Colonization Society, to which Garrison belonged for a time, had this as a goal. (Lundy also belonged.) It also had a number of people who wanted to achieve that goal but maintaining slavery as a legally protected institution in America. He later decided that he didn't agree with that ultimate goal and left the organization.

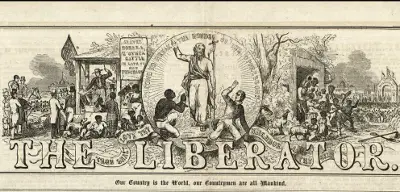

In 1830, Garrison, with business partner Isaac Knapp, started his own newspaper, The Liberator, with the express purpose of promoting the abolition of slavery. He said, "I am in earnest. I will not equivocate. I will not excuse. I will not retreat a single inch, and I will be heard." He published a weekly edition for more than 30 years, advocating the immediate emancipation of everyone enslaved. He furthered the cause by forming two abolitionist organizations, the New England Antislavery Society in 1832 and the American Antislavery Society in 1833. Famous members of the latter group included women's suffrage movement leaders Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucy Stone. The abolitionist movement had one overall goal, but many who favored that goal disagreed on how to achieve it. Many abolitionists were in favor of abolishing slaves and preserving the Union. Garrison, who thought that the Constitution had a pro-slavery slant to it, said that he would accept the dissolution of the Union if it meant that slavery was abolished. One of his more famous quotes was this one: "If the State cannot survive the antislavery agitation, then let the State perish. If the Church must be cast down by the strugglings of Humanity to be free, then let the Church fall and its fragments be scattered to the four winds of Heaven, never more to curse the earth." (He was highly critical of Christian church leaders who refused to condemn slavery.) He also gained notoriety for burning a copy of the Constitution at a public meeting.

Normally a pacifist, Garrison was not averse to advocating violence, either, if it meant that slaves would go free. He used space in The Liberator to praise the actions of Nat Turner, who led a slave revolt in South Carolina, and John Brown, who led a drive to seize the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry and use the weapons to arm slaves. These and other opinions led to the splintering of the American Anti-Slavery Society, with many leaving to form another group fighting for the same ultimate goal. Garrison also objected to both the annexation of Texas and to war with Mexico. He found a kindred spirit in Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave who was a powerful, well-known abolitionist who made speeches against slavery all around the country and urged lawmakers to do everything they could to free people still in slavery. Garrison and Douglass made a number of anti-Union speeches together. A political rift between the two men a few years later resulted in an animosity that did not diminish. Garrison was as strident as he was passionate about emancipation and was known for his fiery rhetoric and sometimes incendiary writings. He lost a libel suit in 1830 and refused to pay the fine. Instead, he served 44 days in jail. He once so angered a mob in Boston that they physically removed him from his office and paraded him through the streets with a noose around his neck. The sheriff spirited Garrison away and kept him safe by keeping him behind bars for a time and then secretly escorting him out of the city. He was also a target of violent intent in the South. More than one Southerner offered a hefty reward for the silencing of the The Liberator and its editor. Garrison married Helen Benson in 1834. They eventually had seven children, five of whom survived into adulthood. Garrison continued his weekly newspaper diatribes against slavery and against the federal government for allowing it. When the Civil War began, Garrison expressed his support for the Union and the war effort in general and for Abraham Lincoln in particular. He continued this support throughout the war. He was also an outspoken of the American Colonization Society, which advocated transporting African-Americans to West Africa as a way to escape slavery and discrimination in America. The ratification of the 13 Amendment in 1865 meant that slavery was officially outlawed nationwide. Garrison ended publication of The Liberator, declaring victory. He retired from public life. Garrison wrote the occasional article in other publications, advocating equal rights for African-Americans and for women. He had refused to take his seat at a meeting of the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840 because the American women who went with him were not allowed to attend. He spoke out more and more in support of the women's suffrage movement. He died in 1879. His wife had preceded him in death by three years. They left behind four sons and a daughter. Frederick Douglass gave the eulogy at Garrison's funeral, saying, in part, "He moved not with the tide, but against it. He rose not by the power of The Church or the State, but in bold, inflexible and defiant opposition to the mighty power of both. It was the glory of the man that he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result." |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White