The American Colonization Society

Many European-Americans championed this idea as a sort of compromise, a way to alleviate tension without resorting to bloodshed. Some African-Americans as well welcomed the idea of leaving America altogether. Other African-Americans, such as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, spoke out strongly against this idea.

In 1816, an educator and Presbyterian minister from New Jersey named Robert Finley established the American Colonization Society (ACS), the goal of which was to support the migration of free African-Americans to Africa. Finley gained the support of many prominent Americans, both black and white, and the ACS in 1821 established a colony on West Africa's Pepper Coast, near the British colony of Sierra Leone. The first president of the ACS was Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington, a Virginia slaveowner who had inherited Mount Vernon from his uncle George Washington. Other founding members were Richard Bland Lee and John Randolph.

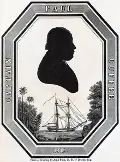

Another American who laid the groundwork for the society was Paul Cuffee, a shipowner who had Native American and African parents. He used his own money in 1815 to pay for the transport of 38 freed African-Americans to Sierra Leone; he returned the following year with another group of settlers. He died during another voyage in 1817. His voyages inspired others to join the ACS and to support its efforts. Many in the ACS were in favor of the abolition of slavery and truly thought that helping African-Americans leave the country was a way to avoid the race-based discrimination that was so prevalent. The society also had as members a number of slaveholders, who also favored the idea of helping free African-Americans leave the country. Famous members of the society included James Madison, who served as ACS president in the early 1830s, and Henry Clay, who was president in the 1830s and 1840s. Other well-known supporters of the society's efforts but not necessarily society members were Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and Daniel Webster.

The ACS bought a ship, the Elizabeth and sailed it several times from the American Northeast to West Africa. The first voyage left New York on Feb. 6, 1820, with 88 African-American emigrants onboard. Some members of the society contributed to its efforts by paying money to secure the freedom of slaves and then paying for their journey across the Atlantic. The society enjoyed donations from individuals and from several state legislatures.

The ACS achieved one of its primary goals with the foundation of Liberia in 1822. Residents of the colony named their capital Monrovia, after James Monroe. More than 4,500 African-Americans moved from America to Liberia in the first quarter-century of the country's existence. The ACS controlled the Liberia colony until 1847, when residents declared themselves independent. The U.S. Government officially recognized Liberia as a country in 1862. One detail that members and the supporters of the ACS failed to prioritize was the susceptibility of those making the journey eastward across the Atlantic was that many of those people had been born in America or had lived there for quite awhile and, as such, had not built up immunity to the kinds of tropical diseases that they encountered when they arrived in West Africa. About 60 percent of those that the ACS helped move to Liberia died within 20 years of arrival, either from diseases or from the sometimes harsh conditions that they encountered in their new homeland. The total number of African-Americans helped to Africa by the ACS topped 13,000. After the end of the Civil War and the Abolition of slavery, interest in the ACS's efforts declined. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln considered supporting the idea of colonization for African-Americans for a time but eventually decided against it. His creation of the Freedmen's Bureau, to help former slaves succeed as free men and women after the war, cemented his change in thought and policy. In this, Lincoln joined with other European-Americans, notably abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who strongly opposed the efforts of the ACS. The society continued to operate, on a smaller scale, for decades. It was dissolved formally in 1964, at which time society officials donated their records to the Library of Congress. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White