Confederate General James Longstreet

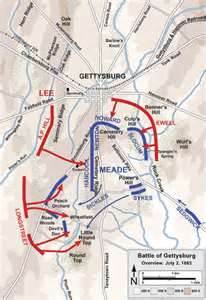

At Gettysburg on the morning of July 2, cavalry commander Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, usually Lee's "eyes and ears," had not returned from an expedition to ride entirely around the Union army and report back, and so Lee did not have an accurate accounting of the Union forces or their positions. Longstreet advised against an assault on what he thought to be a superior Union position. The defense-minded Longstreet preferred to have the enemy come to him. Still, Lee was confident in his troops and in their ability to overcome long odds, as they had done for two years. Lee decided to attack.

Longstreet was to take his First Corps and assault the Union left, with support from A.P. Hill's Third Corps. The Second Corps, under Early, was to make an assault on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. The attacks were meant to happen early in the day. Various delays meant that the attacks did not begin until much later, giving Union troops time to reinforce their positions and, in some cases, move troops altogether. As a result, what was meant to be an assault by Longstreet's troops on a flank of the Union army was instead an attack on the center of the line, mainly because Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles had marched his entire III Corps and their artillery to higher ground along nearby Emmitsburg Road. Confederate troops, when they eventually did attack, were beset on both sides. In areas known as Devil's Den and the Wheatfield, the fighting was fierce, but the result was that Union troops still held the high ground. The disastrous "Pickett's Charge," technically under Longstreet's command, happened the following day, and the failure of that initiative convinced Lee to head back south.

The following month, Davis and Lee approved Longstreet's appeal to head west. He and his men arrived at Chickamauga just in time to provide a needed lift to the Confederate troops there and pave the way for victory. The commander of the Army of Tennessee, Braxton Bragg, sent Longstreet and a group of troops to battle against Union troops at Knoxville. After the Union victory there, Longstreet and his men answered the call to return to the Army of Northern Virginia. In March 1864, President Abraham Lincoln named Ulysses S. Grant general-in-chief of all Union armies. Grant set out on the Overland Campaign, which was designed to target both Lee and Richmond. The first battle in this campaign took place at the Wilderness in May 1864. A large Union force had reached the vicinity of the battle at Chancellorsville the year before. As so often happened during the Civil War, Lee knew the whereabouts of the Union army. The veteran Confederate commander sent his troops numbering 65,000 east on the double. They camped on the night of May 4 just three miles from the Union army. Lee had also sent word to Longstreet to leave his position at Gordonsville and join Lee at the Wilderness. The next day featured desperate fighting, with neither side able to take true advantage. Brambles and branches, roots and stumps stood in the way of both armies as they struggled for purchase in the dense aptly named Wilderness. The smoke from weapons discharges stayed within the umbrella of trees, creating an unnatural fog into which few could see clearly. Friendly fire injuries were rife, as were shots fired at nothing at all. On the following day, May 6, Union troops attacked at first light. Their superior numbers pushed Hill's men back nearly to Lee's headquarters, at Widow Tapp Farm. With their backs against the wall, the Confederates could only hope that Longstreet and his men would arrive. They finally did, jumping into the fight with a furious counterattack along the Brock Road line that, along with another counterattack by troops under Gen. John Gregg, forced the Union troops to give ground. A number of Confederate troops discovered that an unfinished railroad grade gave them excellent cover from which to fire indiscriminately at soldiers dressed in blue. Lee ordered another attack late in the day that gained no purchase. The only Confederate success on the day, other than repulsing the Union advance, was to exploit a weakness on Sedgwick's right flank. Union troops there gave way and were saved from further retreating action by darkness.

Longstreet sustained serious injury during the battle and spent five months recovering. He was shot (by friendly fire) in the neck and right shoulder, and his right arm was thereafter paralyzed. He returned to Lee's fold just in time to direct the defenses at Petersburg. The fortifications were so intense and widespread that the smaller number of Confederate troops were able to hold off attacks by the larger Union army until Grant decided to settle in for a siege. Union troops succeeded in isolating Petersburg, cutting off most of its supply lines. Skirmishes continued into September and through October, and then both sides settled in for the winter. A brief battle at Hatcher's Run in February 1865 was inconclusive. However, the winter, the lack of reliable supply lines, and the length of the siege had taken its toll on the Confederate army. A breakout attempt in March came to nothing. On April 2, during a mass assault on the Confederate line, Lee ordered an evacuation of Petersburg. Longstreet accompanied Lee and the remainder of the Army of Northern Virginia to Appomattox and joined Lee in surrendering to Grant, on April 9, 1865. After the end of the war, Longstreet worked in the private sector in New Orleans, at one time as a cotton broker. A friend of Grant from before the war, he endorsed the latter during his presidential run in 1868. Grant, after winning the election, rewarded his old friend by naming him first as Surveyor of Customs for the Port of New Orleans and then as Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

Longstreet was the adjutant general of the Louisiana state militia in the 1870s and led a group of African-American soldiers in a violent struggle against the White League in 1874. This, coupled with his support for Grant, earned him much enmity in the South. In later years, he served as a railroad commissioner and wrote his memoirs, From Manassas to Appomattox, which were published in 1895. Longstreet died on Jan. 2, 1904, at Gainesville, Ga.; he was 82. He had married twice, to Maria Garland in 1848 and (Maria having died in 1889) to Helen Dortch in 1897. He had in all 10 children. He was variously known as "Old Pete," after the nickname of Peter that his father gave him, and as "Old Warhorse," as given him by Lee. First page > To the Heights of Victory > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White