The Story of the Gettysburg Address

On July 1–3, 1863, Union armies under the command of General George Gordon Meade fought Confederate armies under the command of General Robert E. Lee near a Pennsylvania town called Gettysburg. It was the latest in a series of battles between North and South in a war that had dragged on for years on the battlefield but had been decades in the making. The Union victory at Gettysburg turned Lee's forces back southward (for the last time, although no one knew it at the time) but resulted in a large number of casualties, 25,000 on the Union side and 28,000 on the Confederate side. In keeping with the custom, the troops buried the dead on the battlefield. A few months after the battle, a Pennsylvania lawyer, David Wills, began a drive for a national cemetery. The result was the Soldiers' National Cemetery, which was dedicated with great fanfare on Nov. 19, 1863.

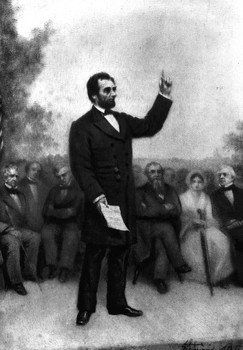

Wills secured the great orator Edward Everett, who counted stints as Governor of Massachusetts, a member of the House of the Representatives and of the Senate, and Secretary of State (under President Millard Fillmore) among his accomplishments, to give the major dedication address. Almost as an afterthought, Wills invited President Abraham Lincoln. The dedication ceremony was one of great fanfare, with a military band and procession and a crowd estimated at about 20,000. The cemetery was full of soldiers who had died on the battlefield at Gettysburg. These "honored dead" were buried in ground next to the old town cemetery. All around were the violent results of the battle. Nearby was a sign that read: "All persons found using firearms on these grounds will be prosecuted with the utmost rigor of the law." Everett spoke for about two hours. Lincoln spoke for two minutes. But it is Lincoln's speech that, despite his assertion that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here," is remembered, often quoted, meticulously analyzed, and revered. The early part of the Civil War was a struggle for both sides to establish military support for their political ambitions. The Southern states wanted to maintain their way of life, in which state governments had more say and in which slavery was allowed to flourish in support of an economy that largely depended on that forced labor. Confederate armies were determined to defend their newly coined country from invasions by Northern troops. The Northern states wanted to stop the spread of slavery (or, in the case of the abolitionist movement, eliminate it) and for the country to be whole again. Union armies aimed to take back possession of secessionist lands, by force, if necessary. (And, as it turned out, force was very much necessary.) From the early Confederate successes at Bull Run through the repeated repulsions of Union advances at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, the Confederate commanders gained confidence in their ability to win at long odds. Union troops often outnumbered Confederate forces, yet the Southern victories piled up, under Lee and Longstreet and Jackson and other excellent strategists. An emboldened Lee ordered a Southern invasion of the North. The two large armies met by chance at Gettysburg. After three days of intense fighting, during which the Union occupation of high ground and overall superiority in manpower and machinery proved determining factors, the Battle of Gettysburg was at an end.

For Lincoln, the war was first and foremost about preserving the Union, intact, with all of its states within its political boundaries. He opposed slavery as morally abhorrent and also saw the war as a means to eradicate enslaved labor. He saw in his Gettysburg speech an opportunity to share with his audience some of his thinking. Lincoln had known for a few weeks that Wills wanted him to speak at the ceremony. He wrote about half of the speech in Washington, D.C., and the rest at Wills' house the night before the dedication ceremony. (The legend about Lincoln's writing the speech on the backs of envelopes while on the train from Washington is just that, legend.) Like Everett, Lincoln was known to have given very long speeches in his career. The speeches he made during the famous Lincoln-Douglas Debates were by no means short. On this occasion, however, Lincoln's were short and to the point. Despite being only 272 words, his speech was filled with allusions to other famous works, including the Declaration of Independence, the Bible, and Pericles' Funeral Oration. He spoke of overarching themes like equality, freedom, and representative government. He included metaphors of people's lives: the nation was "conceived," the nation "might live," the government "shall not perish." Significantly, he referenced the Declaration of Independence, with its statement that "all men are created equal," not the Constitution, which included the Three-fifths Compromise for how to count slaves in the overall population. He spoke to honor the dead but reminded his listeners of the "unfinished work" that, although it had been "nobly advanced," was also a "great task remaining." The reception to Lincoln's speech was mixed. Everett was certainly impressed, telling Lincoln afterwards that "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes." Newspaper accounts of the speech followed partisan lines, with Republican-leaning papers calling it a triumph and Democrat-leaning and Southern papers having less kind words. In the days following the speech, Lincoln wrote out different versions of what he said or meant to have said. Five have come down to us:

The war went on, and on, finally ending in 1865, well after many thought that the victory at Gettysburg would have advanced. Lincoln gave many speeches after the Gettysburg Address, including his famous Second Inaugural, but none remains as famous as the short one. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White