The American Civil War

Part 4: Antietam and Fredericksburg

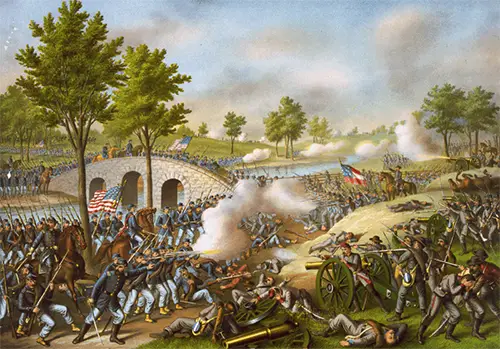

Union forces made three major attacks on Stonewall Jackson's men on the Confederate left, on the Sunken Road. Leading the first attack was Gen. Joseph Hooker; the second attack commander was Gen. Joseph Mansfield; then came the men reporting to Gen. Edwin Sumner. None of those three major attacks, savage and unrelenting as they were, forced the defenders to break ground and flee.

Attacking the Confederate right were men under Gen. Ambrose Burnside, who battled for three hours to take a vital bridge and then, for some reason, delayed a further attack; by the time that Burnside's men advanced again, reinforcements in the form of General A.P. Hill's men had arrived from Harpers Ferry and plugged the gap in the line. McClellan's plan was for the attacks on the left and the right to drive those men back, so a strong attack could be made on the center. The fierce Confederate defense prevented this from happening, and McClellan held back a sizable force from the fray; the reserves were intended to force the issue in the center. Thus, total numbers committed on both sides were roughly equal. Union troops at the beginning of the battle numbered 87,000; Confederate troops at the beginning of the battle numbered 45,000. As had already happened, McClellan was convinced that Lee had more troops than he actually did. The two armies fought each other to a standstill, as darkness ended the fighting. Confederate casualties were large: 9,298 killed or wounded. The total convinced Lee to retreat back across the Potomac, to the relatively safe haven of Virginia. Lincoln visited McClellan at Sharpsburg and, on November 5, removed him as head of the Army of the Potomac and ordered to him to his home in Trenton, N.J., there to await further orders. None came, despite further Union defeats, some spectacular. McClellan spent the next two years writing up reports of his time in command. Lincoln considered Antietam a victory enough to bolster his case for announcing the Emancipation Proclamation, which, as of Jan. 1, 1863, decreed that all slaves in Confederate-occupied territory were free. Newspapers across the North published the Proclamation on Sept. 23, 1862. Replacing McClellan as head of the Army of the Potomac was Ambrose Burnside, whose charge had secured a vital bridge during the Battle of Antietam. Lincoln, Burnside and company decided that the next target for the Army of the Potomac should be Fredericksburg. However, the first action would be one of deception. Burnside planned to make it look like his troops were converging on an area southwest of Manassas, then move at great speed to the real target, Fredericksburg. The plan was to keep Lee guessing about the Union army's true target long enough for the Union troops to slip away unnoticed. Union troops marched to the southwest, converging on the town of Fredericksburg, which was south of Washington, D.C, down the Potomac River. The town was on the southern bank of the Rappahannock River, and Union troops would have to cross the river in order to attack the town. Burnside had decided that the way to do this was to use a number of pontoon bridges to ferry his troops across the river. The troops arrived long before the pontoon bridges did, and Burnside and his commanders decided not to risk having their soldiers wade across the river. While the Union troops waited for their pontoon bridges to arrive, Lee and his army, having not taken the bait, converged on Fredericksburg, filling it with Confederate troops. More importantly, they seized the high ground, installing big gun batteries and large numbers of troops on Marye's Heights and Prospect Hill that would be quite defensible as long as the ammunition did not run out.

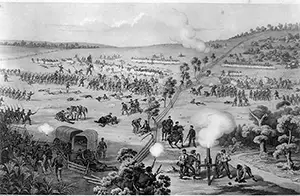

Under pressure from Lincoln and others in the high command, Burnside ordered an assault to begin on Dec. 11, 1862. The first order of business was to assemble the pontoon bridges. Those doing the assembling were soldiers and engineers, who completed their vital task while being subjected to withering enemy fire. Returning fire as much as possible, Union troops provided enough cover to enable the completion of the pontoon bridges, which the troops then used the following day to cross the river, again under hails of gunfire. On December 13, Burnside ordered a full assault all along the line. The Union troops marched across open ground, firing and reloading as they went, with the aim of reaching the high ground and dislodging the defenders. The total number of troops in the Union force for this battle was 120,000; Confederate troops numbered 85,000. However, the defensive positions set up by Lee and Maj. Gen. James Longstreet were nearly impregnable and made it easy enough to continue mowing down advancing Union soldiers. The carnage was particularly heavy. Lincoln relieved Burnside of his command and replaced him with Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who had led one of the futile assaults on Fredericksburg. Next page > Chancellorsville and Vicksburg > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Chance intervened, as a Union soldier found a copy of Lee's troops movements. A Union victory at South Mountain presaged the next encounter, at Antietam Creek, near the town of Sharpsburg. There, on September 17, the Union and Confederate forces clashed in

Chance intervened, as a Union soldier found a copy of Lee's troops movements. A Union victory at South Mountain presaged the next encounter, at Antietam Creek, near the town of Sharpsburg. There, on September 17, the Union and Confederate forces clashed in