The weather

The original date planned for the invasion was June 5. Weather forecasts for that day predicted rough seas and overall terrible weather in general, certainly not the kind that lent itself to transporting large numbers of men on ships across open water. Eisenhower and his commanders decided to postpone the attack for a day. Because of the precise needs with regard to tides, the moon, and other concerns, military planners had advised that only a few days each month were suitable. If the attack did not take place on June 6, then the next clear window was two weeks away. Late in the day on the 5th, a meteorologist predicted a break in the storm pattern of several hours. That was enough for Eisenhower. D-Day was the 6th. The buildup

To get to the points of departure, the tens of thousands of soldiers who left for the beaches of Normandy travelled on foot and by vehicle through the narrow roads of southeast England for severals before June 6. Some soldiers arrived days ahead of time; others arrived just in time. Equipment, supplies, weapons, and food and drink were plentiful, as was organization. The departure

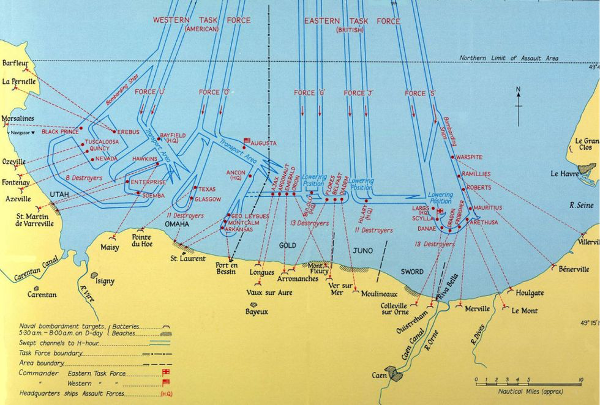

Ships left a number of harbors, including Bournemouth, Eastbourne, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Southampton, Torquay, and Weymouth. After a stop off at the Isle of Wight, it was all hands on deck for the trip south to Normandy. The landing craft traveled through a relatively narrow stretch of water known as the Spout. Transporting and supporting those troops were nearly 7,000 seagoing vessels, more than half of which were landing craft; among the other types were battleships, cruisers, destroyers, minesweepers, and submarines. Also supporting the landings were nearly 12,000 aircraft. Also traveling through the Channel was a very large amount of concrete, in the form of two "Mulberry" artificial harbors and five "Gooseberry" breakwaters. The Normandy beaches had no harbor, so the Allies had chosen to provide their own. Departure was soon after midnight. The seas were rough, with five-foot waves; a great number of the Allied force got seasick.

Next page > On the Beaches > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Eisenhower said to his troops, "You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you."

Eisenhower said to his troops, "You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you."