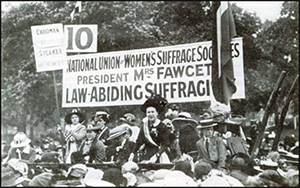

U.K. Women's Suffrage: Millicent Fawcett and the NUWSS

The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies arose in 1897 from the merger of a number of similar groups, all focused on gaining the vote for women in the United Kingdom. The most well-known member of the society was Millicent Fawcett.

A group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society in 1865. The name of the group came from the group's meeting place, 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington, which was the home of the group's founder, Charlotte Manning. It wasn't only in London that such groups were forming in the 19th Century. One of the original members of the Kensington Society, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, started the Manchester Committee for the Enfranchisement of Women. Other cities and towns were soon home to similar groups. Two years after the formation of the Kensington Society, Parliament passed the Reform Act 1867, which added many more men to the voter rolls. During debate on the bill, John Stuart Mill, an MP and well-known philosopher and author, proposed that women should be given the same voting rights as men. Mill proposed this as an amendment to the bill that was eventually passed by Parliament; among the overwhelming number of those who voted against Mill's amendment was then-Prime Minister and noted reformer William Gladstone. More gallingly to those championing women's suffrage, this reform act specifically defined a voter as being male. In response, the members of the Kensington Society formed a new organization, the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Emerging from this new group as a powerful and outspoken leader was Millicent Fawcett, who had been with the Kensington Society from its early days. (She had been Millicent Garrett; in 1867, she married Henry Fawcett, who represented Brighton the House of Commons.) She embarked on a number of speaking engagements, to try to help convince people to support the idea of women's being able to vote.

Mill lost his re-election bid to the House of Commons, and the leader in Parliament of the drive toward granting women the vote became Jacob Bright. He and Sir Charles Weltworth Dilke introduced the first women's suffrage bill in 1870; it was resoundingly defeated. They tried again the following year; Gladstone was instrumental in its defeat. At Bright's suggestions, Fawcett and others formed a new group, with the goal of pressuring the House of Commons to approve women's suffrage. This was the Central Committee for Women's Suffrage. Among the members of this group was noted nurse Florence Nightingale. Even though Gladstone and the Liberal Party won the 1880 general election, the normally reform-minded party did not have any sympathy for women's plight as nonvoters; the same could be said for Queen Victoria, who, despite her gender, was a very conservative politician and saw no reason for women to be able to vote. The Third Reform Act, also known as the Reform Act 1884, added another handful of million men to the voter rolls but no women. The number of women's suffrage groups proliferated, and many in the public became confused as to the exact nature of the message. Estimates are that in the 1890s, no fewer than 17 individual groups were pursuing basically the same agenda. Thus it was in 1897 that a number of groups joined together to form the NUWSS. The members of the NUWSS preferred to follow a constitutional path to success. They wanted the law to change and believed that legal means of advancing their arguments were more effective than the sort of outlandish, even violent methods employed by members of other suffrage organizations, such as the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), which formed in 1903 as a splinter group from the NUWSS. Among the strategies that Fawcett and others in the NUWSS advocated were these:

The NUWSS, as the merged group was known, grew by 1914 to more than 500 branches throughout the U.K. and more than 100,000 members. The NUWSS supported the war effort. Fawcett firmly believed that after the war, both women and men would see that women deserved the vote, especially after all of the work that they had done during the war, such as helping look after the families of veterans and augmenting the work of military nurses. One of the major arguments that women could make after the war, the NUWSS believed, was that women had done during the war many jobs that were previously done only by men and that women had done those jobs well; if women could do the same job as a man could, then surely a woman could vote just as a man could, so the theory went. Parliament agreed, in part. The Reform Act 1918 did give the vote to women, just not all of them. This bill that brought monumental change was the final step in bringing universal suffrage to men. And, it was the first bill to grant the right to vote to women. The only remaining qualification for a man to be able to vote was that he be 21 or older. Women who wanted to vote had to own property (or be the wife of a property owner), and be 30 or older. This amounted to an addition of 6 million women to the voter rolls. The NUWSS, having not really achieved its goal, carried on, changing its name to the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship. A new leader, Eleanor Rathbone, took the reins and guided the organization through the next several years. Finally, in 1928, Parliament granted women the same voting rights as men: the only qualification being age 21 or older. Members of the NUWSS were also known for saying that they were suffragists, not suffragettes, the latter being a derogatory term assigned to proponents of women's suffrage by a U.K. newspaper. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

having public meetings to discuss the reasons for making such a change

having public meetings to discuss the reasons for making such a change