William Gladstone: Lion of Reform

Part 1: Rise to Success William Gladstone was a four-time Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and a noted champion of reform. His is one of the most familiar names in U.K. politics. He was born on Dec. 29, 1809, in Liverpool. His father, Sir John Gladstone, was a wealthy merchant who owned a number of sugar plantations in the West Indies and also made money in the corn and tobacco trades.

Young William attended a local prep school and Eton College and then Christ College, Oxford, graduating in 1828. A member of the Oxford Union Debating Society, he became known as a top-notch public speaker. He won the seat for the Newark constituency in the 1832 parliamentary elections, representing the Conservative Party, and joined the House of Commons. The Newark seat was one that had survived the culling created by the Reform Act 1832, which Gladstone had opposed. His father was a slaveowner and, following the abolition of slavery in 1833, helped his father get compensation for the slaves who were freed. In 1834, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel appointed Gladstone junior lord of the Treasury. A further appointment came the following year: undersecretary for the colonies. When Peel resigned later that year, Gladstone lost his job; he remained in Parliament, however. In that same year, 1834, Gladstone married Catherine Glynne. They were married 59 years and had eight children. Peel was again Prime Minister in 1841, and again Gladstone found himself with a high-level job, this time as vice-president of the board of trade. Two years later, he became president. Gladstone shepherded the Railway Act through Parliament in 1844. This law required railroad companies to do more to look after low-income customers. A railway had to run a passenger once a day and charge of only one penny a mile, and the carriages on that train had to had seats such that passengers could sit and be protected from the weather. (It was not uncommon for railway passengers at this time to stand in uncovered carriages.) When Peel threw his weight behind the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, it cost the Prime Minister his job and had splintered his Conservative Party. Gladstone had supported Peel and the repeal and, the following year, won a seat representing Oxford University. Lord John Russell was the Prime Minister who took over for Peel. Succeeding Russell in 1852 was Lord John Russell, and it was Russell who named Gladstone Chancellor of the Exchequer. Another new Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, took over in 1859. Palmerston was a member of the other dominant political party, the Whigs, but offered to keep Gladstone as Chancellor of the Exchequer anyway. Coincidentally or not, Gladstone then left the Conservative Party.

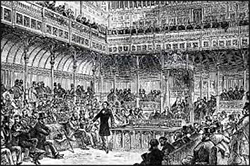

Gladstone paid the political price for leaving the Conservative Party in 1865 when he did not win re-election for his Oxford seat. He did find his way back into Parliament, however, representing South Lancashire, as a member of the Liberal Party. This was the second instance of Gladstone's claiming representation from a "new" constituency: The Reform Act 1832 created South Lancashire. Gladstone had earlier opposed electoral reform. After three decades of observing the working classes and their inability to be properly represented in Parliament, he changed his mind. In 1866, Gladstone introduced a reform act. It did not find immediate acceptance. Prime Minister Russell resigned in June, and the Conservative leader Edward Stanley, Early of Derby became the parliamentary leader. Russell retired from politics in 1867, and Gladstone succeeded him as leader of the Liberal Party. The leader of the House of Commons at the time was the Conservative Benjamin Disraeli, and it was he who proposed what would eventually become the Second Reform Act. After weeks and weeks of furious debate and various amendments' being added and subtracted–not to mention a public gathering in favor of the bill that numbered in the Gladstone continued as leader of the opposition. The Prime Minister resigned in 1868 and was replaced by Disraeli. Gladstone, as leader of the opposition, heavily criticized Disraeli's policy with regard to reports of brutality in the Balkans. In the general election that followed, the Liberal Party won more than 100 more seats than the Conservative Party and so Gladstone became Prime Minister. Next page > Longtime Leader > Page 1, 2

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

tens of thousands of people–the House of Commons passed and the House of Lords validated the

tens of thousands of people–the House of Commons passed and the House of Lords validated the