King William II of England

He was born in Normandy in 1056, the third son of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. His oldest brother was Robert, known as Curthose, born in 1054. The brother just older than William was Richard, born in 1054. William's youngest brother was Henry, born in 1068. William, who had been Duke of Normandy, had conquered England, defeating King Harold and his Saxon army at the Battle of Hastings, and assumed the kingship in 1066. He sent his sons off to study with the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The idea for succession was that William, who owned both England and Normandy, would divide his lands between his first and second sons, with Robert (known as Curthose), the oldest, getting Normandy and Richard, the second-oldest, getting England. William, as the third son, would join the Church. Henry would do the same or be otherwise engaged and so not be expected to be the ruler of any lands. Richard died in a hunting accident in 1074, elevating William to the nominal position of second son. William stopped his religious training and became an apprentice to his father. In 1087, William made it official, designating Robert as the future ruler of Normandy and William (his son) as the future ruler of England. William (the Conqueror) died that year. William became King William II of England. Robert became Duke of Normandy. Henry got a large sum of money but no land.

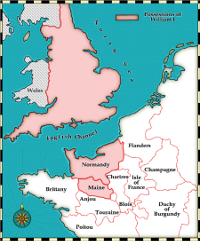

Many nobles had lands in both England and Normandy. When William I was king of both areas, the nobles knew whom to serve. Now that the lands were divided, the nobles had divided loyalties. William didn't help his cause by displaying a penchant for cruelty and greed. He and his chief minister, Ranulf Flambard, levied heavy taxes on the nobles and the Church and pursued fiscal policies that angered the Church, such as diverting funds intended for the clergy into the royal coffers instead. He also banished Anselm, the Archbishop of Clergy, to Normandy. William also needed money to support the various wars that he fought, at his own instigation or as defensive actions, against incursions by Scottish and Welsh armies. He savagely put down an invasion by King Malcolm III of Scotland and a rebellion by Robert de Mowbray, the earl of Northumbria. He even picked a fight with King Philip I of France, which went nowhere. Another way in William Rufus angered the populace was by pursuing a draconian interpretation of the Forest Laws, which his father had instituted with the idea of protecting game animals and their forest habitat from destruction by human settlement. William I decreed severe punishments for breaking these laws; William II made the punishments even harsher: anyone who killed a deer was put to death; anyone who shot at a deer lost the hands that held the bow; anyone who even disturbed a deer was blinded. Many of the nobles threw in their lot with Robert and encouraged an invasion of England, so Robert could follow in his father's footsteps and be king of both England and Normandy. Leading this uprising, known as the Rebellion of 1088, was Bishop Odo of Bayeux, who was the half-brother of William the Conqueror. The nobles hired a mercenary force and went to England; Robert did not appear. William successfully defended England. The following year, William took the fight to Robert and invaded Normandy, forcing his brother to terms very favorable to William. In 1096, Robert was seized with a fervor to go off to a foreign land and fight. He went off to fight in the First Crusade, the first several attempts by Western forces to take back ownership of the Holy Land from Muslim armies. Robert and William, who had uneasily reconciled, made a pact (which Robert sealed by giving his brother a lot of money, which he got by levying yet another tax on his subjects) that made William regent of Normandy while Robert was away. They agreed that if one of them died without an heir, the other would be ruler of both England and Normandy. Robert was away on Crusade until September 1100. He returned and resume control of Normandy. However, in England, he found his brother William dead and his brother Henry king.

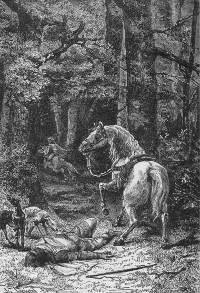

On Aug. 2, 1100, William Rufus had gone on a hunting expedition in the New Forest. William had had an ominous dream the night before in which he was being attacked; he put that aside and went on the hunt. His brother Henry was with him, as were several nobles. The king and nobles were chasing after a stag when the king shot an arrow at the stag and missed. He implored one of his nobles, Walter Tyrrell, to shoot at the stag. Walter's arrow missed the stag and hit the king in the chest. The king died on the spot. Walter fled for France, never to be seen. Henry fled for Winchester, to seize the royal treasury, just as William had done when their father died. The other nobles scattered. A group of local farmers found the king's body the following day and took it to Winchester Cathedral. The king was buried under a plain marble stone. The day after his funeral, Henry was proclaimed king. William had never married or had any children.

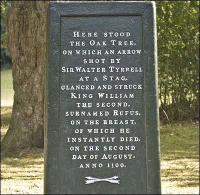

A memorial stone in the New Forest, known as the Rufus Stone, is on the spot where the king is believed to have died. Among the words on the stone are the idea that the fatal arrow bounced off a tree before striking the king. Whether the king was murdered has been debated through the years. His brother, who would benefit from his death, was in the hunting party. Walter Tyrrell, who fired the deadly arrow, was an excellent marksman who, many historians say, should not have missed his target so badly, unless he hit his intended target after all. William Rufus is not viewed kindly by many who study this period in history. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle had this to say: "He was very harsh and fierce in his rule over his realm and towards his followers and to all his neighbours and very terrifying. Influenced by the advice of evil councillors, which was always gratifying to him, and by his own covetousness, he was continually exasperating this nation with depredations and unjust taxes. In his days therefore, righteousness declined and every evil of every kind towards God and man put up its head. Everything that was hateful to God and to righteous men was the daily practice in this land during his reign. Therefore he was hated by almost all his people and abhorrent to God. This his end testified, for he died in the midst of his sins without repentance or atonement for his evil deeds." |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

King William II of England was more commonly known as William Rufus. He got his nickname from his red hair and ruddy complexion. (One story says that he got the name because of his quick temper.)

King William II of England was more commonly known as William Rufus. He got his nickname from his red hair and ruddy complexion. (One story says that he got the name because of his quick temper.)