The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

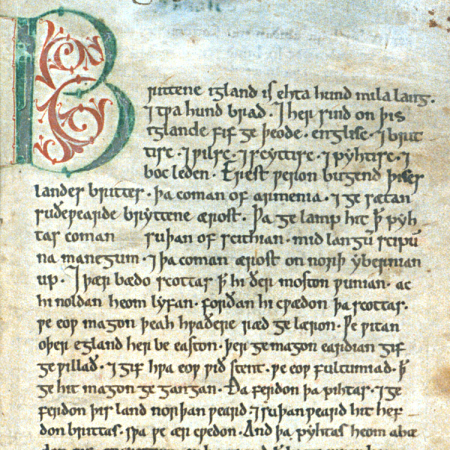

Nonetheless, most scholars view the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as an invaluable window into the goings-on for about 1200 years of English history. Much of the information in the Chronicle does not appear in other sources. As well, the last version, known as the Peterborough text because it was written in Peterborough Abbey, is one of the earliest known examples of writing in Middle English, which was used in the very last entry. The other entries in the Peterborough text and all other entries in all earlier versions were written in Old English. The first entry of any kind is an introduction: The island Britain is 800 miles long, and 200 miles broad. And there are in the island five nations; English, Welsh (or British), Scottish, Pictish, and Latin. The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward. The last entry is for the year 1154, the end of the reign of King Stephen.The first dated entry is for the first invasion of Julius Caesar, which occurred in 55 B.C.; the Chronicle entry is 60 B.C. The second dated entry is for A.D. 1.

The British Library has care of seven of the nine surviving manuscripts; the other two are housed one each at Oxford and Cambridge. Sources for the Chronicle are thought to have been king lists, geneaologies, the Venerable Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and annals from Saxons in Wessex and from the Frankish peoples. One of the king lists that appears in the Chronicle includes the first eight men named bretwalda, a sort of overlord. The entry for 829 reads thus: The moon darkened on Christmas Eve. That year King Egbert overcame the Mercian kingdom, and all that was south of the Humber. He was the eighth king who was ruler of Britain; the first was Aelle, king of Sussex, who had done this much. The second was Ceawlin, king of Wessex, the third was Aethelbryht, king of Kent, the fourth was Raedwald, king of East Anglia; the fifth was Edwin, king of Northumbria; the sixth, Oswald, who ruled after him; the seventh was Oswald's brother Oswiu. The eighth was Ecgbryht, king of Wessex, and this Ecgbryht led troops to Dore against the Northumbrians. They offered him submission, and a treaty; with that they parted' The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle includes descriptions of some of England's most momentous events: The Norman Conquest, 1066: Then Count William came from Normandy to Pevensey on Michaelmas Eve, and as soon as they were able to move on they built a castle at Hastings. King Harold was informed of this and he assembled a large army and came against him at the hoary apple tree. And William came against him by surprise before his army was drawn up in battle array. But the king nevertheless fought hard against him, with the men who were willing to support him, and there were heavy casualties on both sides. Then King Harold was killed, and Earl Leofwine his brother, and Earl Grythe his brother, and many good men, and the French remained masters of the field. The compilation of Domesday Book, 1085: Then he sent his men all over England into every shire to ascertain how many hundreds of "hides" of land there were in each shire, and how much land and live-stock the king himself owned in the country, and what annual dues were lawfully his from each shire. He also had it recorded how much land his archbishops had, and his diocesan bishops, his abbots and his earls, and – though I may be going into too great detail – and what or how much each man who was a landholder here in England had in land or in live-stock, and how much money it was worth. So very thoroughly did he have the inquiry carried out that there was not a single "hide" not one virgate of land, not even – it is shameful to record it, but it did not seem shameful to him to do – not even one ox, nor one cow, nor one pig which escaped notice in his survey. |

|

No one version of the Chronicle exists; in fact, fragments of nine different versions exist. The first has been dated at 892; the last has been dated at 1116. In most cases, the names and places in the Chronicle were the product of writings long after the fact. Also in many cases, the accounts of battles or great deeds represented only one side of the story or were embellished (based on other sources known to conflict with what the Chronicle has.)

No one version of the Chronicle exists; in fact, fragments of nine different versions exist. The first has been dated at 892; the last has been dated at 1116. In most cases, the names and places in the Chronicle were the product of writings long after the fact. Also in many cases, the accounts of battles or great deeds represented only one side of the story or were embellished (based on other sources known to conflict with what the Chronicle has.) Dating for some entries varies, depending on in which version they appear. Accounts of some events and descriptions of some people differ, depending on in which version they appear.

Dating for some entries varies, depending on in which version they appear. Accounts of some events and descriptions of some people differ, depending on in which version they appear.