The Norman Conquest of England

The Norman Conquest was the military and political takeover of Anglo-Saxon England by forces led by William, Duke of Normandy, who was known as William the Conqueror and who, after his victory at the Battle of Hastings, became King William I of England. The Norman presence in England went back as far as 1002, when King Æthelred II married Emma of Normandy. Their son, Edward the Confessor, became King of England in 1042, but not before he had spent several years in exile, in Normandy. Edward had had to flee the country because it had been taken over by Sweyn Forkbeard and his Danish forces in 1013. Edward's father, Æthelred, and mother, Emma, had sought refuge in Normandy as well. Sweyn's death in 1014 resulted in an appeal for Æthelred to return, which he did, retaking the throne. His death in 1016 brought his eldest son, Edmund Ironside, to the throne, but he couldn't hold the throne, either, and another Danish king, Canute, took the throne of England and, in 1017, married Emma of Normandy. Young Edward grew up in Normandy and learned Norman ways of speaking and acting under the protection of Duke Robert. When Robert traveled to Italy for an extended period of time, he left Edward as a guardian of Robert's son William, who would presume on that relationship a bit later in the lives of both men. In fact, William claimed that Edward, when he was King Edward the Confessor, had in 1051 promised William the throne.  William proved his claim and his mettle on the battlefield at Hastings and claimed the throne for himself. He then set about consolidating his claim, reinforced by his victorious army. William did not receive the expected courtesy call to be king because the Witengamot, the kingly council of advisors, had chosen someone else, Edgar the Aetheling, to succeed Harold Godwinson as King of England. William marched his army up to engage a group of soldiers loyal to Edgar and defeated them, at Southwark. William wanted to descend on London, but the most direct route was across an easily defended bridge. Marching on London by a more circuitous route, he fought several smaller engagements, winning them all, and the soldiers and nobles loyal to Edgar surrendered to William at Berkhamsted. William was then crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day.

William stayed in England for a time, handing out land to his onetime opponent, Edgar the Atheleing, as well as to several other nobles. William then took a handful of these men prisoners and returned to Normandy, in March 1067. William left his half-brother, Odo, and a strongman, William fitzOsberg, in charge of England. The once-defeated English found nerve again to attack Norman forces, and William returned to England at the end of the year. William, an adept battle tactician, put down a handful of rebellions and then had his wife, Matilda, crowned queen, as he was at Westminster Abbey. One way that William kept the peace after his victories was by building castles and installing garrisons to man them and patrol the surrounding countryside. This was a change from Anglo-Saxon methodology, which envisioned the castle as more of a defensive structure. This strategy more effectively allowed William to deal with a continuing series of small revolts, in Mercia and then in the West Country (Somerset, Devon, Cornwall). William turned back a determined rebellion farther north, in Northumbria, and then built two castles in York to solidify his control over the north.

The Danes were back in 1069, as Sweyn II sought to duplicate his father's feat by taking advantage of another uprising in Northumbria. The joint Danish-English force was successful for a time, seizing Norman castles and taking control of Northumbria. William responded in two ways–by fighting the English and by paying off the Danes (a strategy employed so successfully by previous English monarchs that it had a name, Danegeld). During the next several months, extending into 1070, William regained control of what he had lost. It was a repeat performance the following year, and William again paid a large sum of money to convince Sweyn II to go back to Denmark. In 1072, William marched north to confront Scottish forces under King Malcolm II. Edgar the Ætheling had fled to Scotland and set about joining a resistance movement there. William was victorious in this struggle as well. These campaigns of William's came to be known as the Harrying of the North and effectively reduced northern resistance to royal power for a considerable amount of time. The final uprising to William's rule occurred in 1075, in what historians call the Revolt of the Earls. William, who was in Normandy at the time, trusted his lieutenants to put down the rebellion, which they did. William returned to England only when yet another Danish raiding force arrived. He sent them packing.

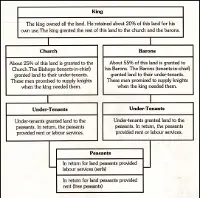

William and his advisors and army then set about remaking the English landscape. One of the main spoils of the Norman Conquest was that the king seized an enormous amount of land to be held in his personal possession, to be doled out as he saw fit. He then gave it to his friends and supporters. Many Anglo-Saxon nobles and soldiers had died, either at the Battle of Hastings or in subsequent fighting. Many more fled England altogether, settling in nearby destinations like Ireland and Scotland or slightly farther away, in Scandinavia. On one occasion, a fleet of 235 ships filled with Anglo-Saxons of every economic class set sail for the far-away Byzantine Empire. As well, William replaced most Church bishops with Norman men and built new cathedrals in the Norman style. The Normans overhauled the geographical systems of government in England, dividing the territory into administrative units called shires. Each shire had a head official, called the reeve. (A corruption of "shire reeve" became the modern word "sheriff.") William kept largely intact other elements of the Anglo-Saxon system, including the tax system. The crown already had a monopoly on minting coins. The official language of official documents changed from Old English to Latin. Anglo-Norman, a dialect of Old French, became the language of the ruling class, also displacing Old English. William introduced the idea of the royal forest, claiming large areas of the country as forest lands owned and protected by the king. The Normans introduced a new system of laws governing the activities allowed in the royal forests.

One of the Norman Conquest's lasting legacies was the creation of Domesday Book, a large collection of detailed information about most of the countryside. William sent out a large number of officials to interview lords of manors and other officials, with an eye toward determining how much tax he could receive. This occurred in the late 1080s, with yet another Scandinavian invasion threatening. Another way in which the Normans changed the countryside was in the materials used to build houses and castles. Anglo-Saxon buildings were, for the most part, wooden structures. The Normans used bricks and stones, creating large and imposing castles, cathedrals, churches, and monasteries all about the land. William died in 1087, leaving his authoritarian kingship model in the hands of his third son, William II (known also as William Rufus). The Norman line of kings would continue for a time; the Norman legacy of change would last much, much longer. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White