The Mighty Legions of Rome

The legion was a resourceful, very successful fighting formation employed by Roman leaders for much of the life of the Republic and the Empire.

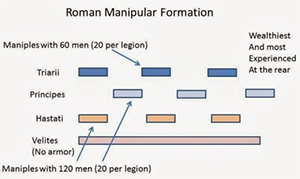

From the founding of Rome, traditionally dated to 753 B.C., to the 3rd Century B.C., Roman armies employed the tried and true phalanx, which served the armies of Alexander the Great so well in his conquest of the Persian Empire. It was in 315 B.C., during the Samnite Wars, that Roman forces first experimented with the maniple, out of desperation after being thwarted by the inability of the phalanx to deliver victory on the rugged terrain of Samnium. The significance in this change was in the choice of weapon and defense mechanism, the former going from spear to short sword and javelin and the latter going from the round hoplon to the rectangular scutum. The new formation had four lines of soldiers, each of which had a different purpose and the inhabitants of which were differently outfitted. The most experienced fighters were the triarii, who the generals saved to turn the tide. The legion came about as a result of reforms introduced by Gaius Marius in 107 B.C. A legion consisted of 4,800 soldiers, divided into 10 cohorts of 480 fighters each. (In Soldiers would sign up to serve for 25 years. When they finished, they could retire and enjoy a small pension and a bit of land as thanks for their service. Both the maniple and the legion allowed the soldiers more flexibility in dealing with difficult terrain or sudden changes in enemy tactics than did the phalanx. A large part of Rome's success was to do with the legions' training, skill, and efficiency. Roman soldiers professed their loyal to Rome and pledged to give their fighting lives to the cause. At various points throughout Roman history, legions switched the focus of their allegiance from the state itself to individual commanders. One of the most famous examples of this was the legions that followed Julius Caesar across the Rubicon, knowing full well that they were marching into a civil war. Another instance was that of the Danube legions who threw their support behind Vespasian, thus ending the Year of the Four Emperors power struggle in his favor. From the time of the Marian reforms, each legion had the eagle as its symbol. The Latin word for eagle was aquila, and the officer who carried the symbol bearing a depiction of an eagle was known as the aquilifer. This was a very important post symbolically. As well, each legion had its own legion-specific emblem, which appeared on a flag-like item. The Latin word for this item was vexillum, and the person who carried it was the vexillifer. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Fighting in the very front lines were the least experienced, the hastati, who fought with a short sword and wore a modest amount of armor. Those soldiers fell on the enemy straight after the velites heaved their javelins at the enemy and then fell back. The stars of the show were generally the heavy infantry known as principes, who boasted more experience and better armor than the hastati. Other soldiers were equipped with other weapons, including bow and arrow. Protecting the flanks of the infantry were the equites (cavalry), who would take off after retreating enemies with lighting speed.

Fighting in the very front lines were the least experienced, the hastati, who fought with a short sword and wore a modest amount of armor. Those soldiers fell on the enemy straight after the velites heaved their javelins at the enemy and then fell back. The stars of the show were generally the heavy infantry known as principes, who boasted more experience and better armor than the hastati. Other soldiers were equipped with other weapons, including bow and arrow. Protecting the flanks of the infantry were the equites (cavalry), who would take off after retreating enemies with lighting speed. some cases, the first cohort had 800 soldiers.) A century was an 80-man-strong subgroup of a cohort. (A century in the early days of the

some cases, the first cohort had 800 soldiers.) A century was an 80-man-strong subgroup of a cohort. (A century in the early days of the