The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire

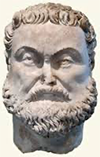

Part 7: Geography and Power-sharing Macrinus didn't last long on the throne, and his death at the hands of the next emperor, Elagabalus, ushered in a period of uncertainty that nearly toppled the Roman Empire. Northern invasions by Germanic tribes were increasing, even as Roman armies were still fighting against enemies in the east. The once mighty Roman armies were finding defeat more and more common, and the mystique of the invincible might of Rome was waning. Instability atop the government didn't help. Another plague, in 251, further weakened the empire as a whole, provoking wholesale migrations. A rise in sea level played havoc with northern peoples, forcing many of them to seek new homes to the south. In the 260s, the Empire underwent a division, as the provinces of Britain, Gaul, and Hispania formed the Gallic Empire and the provinces of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria formed the Palmyrene Empire. The emperor Claudius II Gothicus turned back a Gothic invasion at the Battle of Naissus, in the late 260s, and Rome began to recover. His successor, Aurelian, reunited the empire. Again, progress was short-lived, as Aurelian fell to assassination in 275. Another run of short-term emperors followed. Diocletian in 284 seized power and restored order. Diocletian had studied geography and history and thought that the Empire as it stood in the late 3rd Century was too large for one The two leaders agreed on the direction that the Empire should take and were content operating in their separate spheres. It marked a peaceful change from the several dozens of military anarchy through which the people of the Roman had lived. In the previous 50 years alone, a full 26 had sat on the throne; much of the trouble had arisen from a lack of a strong ruler and/or a known and capable successor. Thinking ahead to the tricky element of succession, Diocletian created a four-man head of government scheme that, with its two tiers of two rulers each, should, he thought, ensure a smooth transition from one ruler to the next. This new plan named Diocletian and Maximian as Augusti. Each of them would have a Caesar under them, as second-in-command, designated to succeed whichever Augustus he reported to, in the event of the top man's death. Maximian chose as his Caesar his Praetorian commander Constantius, whom he also adopted. For his Caesar, Diocletian chose Galerius. The four men divided the Empire between them:

This tetrarchy general did what it was supposed to do, with each of the four men ruling over one-quarter of the Empire and having authority to put down rebellions, such as the one that Galerius dealt with in Egypt in 291–293. In his later years, Diocletian began to think of himself as a living god and demanded that anyone wishing to see him bow before him and then kiss his purple robe. He looked the part by sitting on an elevated throne. Whether intentionally or not, he targeted Christian soldiers and government officials by demanding that all members of both organizations sacrifice to the Roman gods and that anyone refusing to do so would be forced to leave their post. He intentionally targeted Christians in 303 with a directive to destroy Christian churches and writings. The combination of these two things resulted in a large-scale persecution of Christian people within the Empire.

In 303, Diocletian visited Rome (the only time he ever went there). He fell ill and abdicated, in 305, retiring to a very large fortress in Spalatum, in what is now Croatia. He convinced Maximian to abdicate as well, and the tetrarchy swung into action: Constantius and Galerius moved up to being Augusti, and the new Caesars were Maximinus and Severus. In 305, both Diocletian and Maximian, the Augusti (co-emperors) abdicated, and their Caesars, Constantinus and Galerius, became co-emperors. Significantly, the younger Constantinus and Maxentius, the son of Maximian, did not follow in their fathers' footsteps and become Caesars. Instead, Galerius's nephew, Maximinus, and Severus became the co-emperors-in-waiting. Next page > From West to East > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

man to rule effectively. In November 285, he named his son-in-law, Maximian, as commander of the Empire in the West. Diocletian kept power in the East and ostensibly ruled the West as well because he retained for himself veto power over any decisions made by Maximian.

man to rule effectively. In November 285, he named his son-in-law, Maximian, as commander of the Empire in the West. Diocletian kept power in the East and ostensibly ruled the West as well because he retained for himself veto power over any decisions made by Maximian.