The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire

Part 3: To Its Greatest Extent

Vespasian restored order to the army, punishing those who had stepped out of line. He also restored viability to the royal treasury, removing certain tax exemptions and introducing new forms of revenue generation. He spent some of this money on new construction, including the Colosseum. Vespasian's son Titus had returned to Rome in 71 and served as his father's right hand, dictating letters, enacting policy, and protecting his father from plots against him. Vespasian died on June 23, 79. Titus succeeded him peacefully.

Like a great many people in the Roman Empire, Titus was greatly saddened by the loss of life caused by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. At almost precisely noon on August 24, 79, the volcano, which that been quiet for hundreds of years, suddenly spewed forth a huge explosion that rocked the countryside for a huge number of miles around and creating a mushroom cloud of ash and debris 10 miles high. Fire and debris rained on Pompeii, and most people fled. A few, perhaps as many as 2,000, stayed, hoping that things wouldn't get any worse. It did. The very next morning, a cloud of toxic gas, fumes from the volcano, wafted through the city, killing all who breathed it. A rockslide followed, burying the dead where they lay. Herculaneum was much the same story, with the death-dealing blow being a monstrous cloud of hot ash and gas surging through the city, killing all who had stayed. Not long after, a massive rock- and mudslide engulfed the city. Titus toured the area and donated large sums of money to the cleanup efforts in the two devastated areas and to the relief efforts for victims elsewhere.

Titus shared his father's penchant for new construction and ordered the construction of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus and a new imperial baths. He also oversaw the completion of the Colosseum. A full 100 days of celebration marked the opening of the building otherwise known as the Flavian Amphitheater in 80. Gladiator battles, mock naval battles, fights between different kinds of animals, and horse and chariot races punctuated the celebrations. After the great games at the Colosseum closed, Titus left Rome. He died of a fever, on Sept. 13, 81, in the same villa in which his father had died. He was 42 and had been emperor for 2 years, 2 months, and 20 days. His brother Domitian succeeded him. Two years into his reign, Domitian wanted to prove to the people that he was a military man and so went on campaign, in Germany. After a victory over the Chatti, he gave himself the title Germanicus. He proved to the Army that he had their welfare in mind when he became the first emperor since Augustus to give them a raise in salary. He had less success in Dacia, having to sign a peace agreement with King Decebalus.

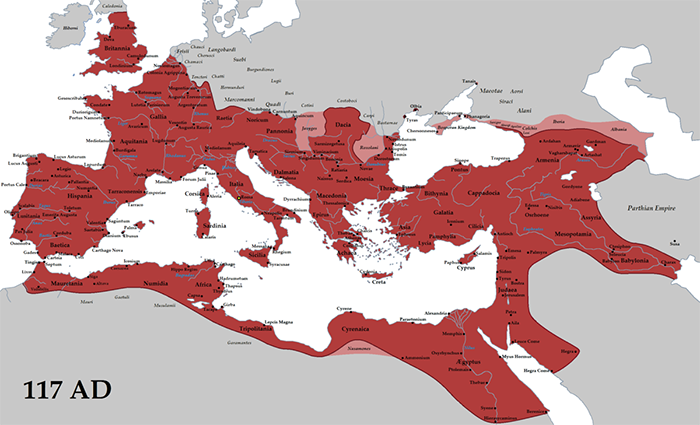

The power of the throne went to Domitian's head, and he ruled as a divinely inspired sole monarch. He declared that he was the sole entity of government. Sidelining the Senate (which despised him in return), he also declared that the head of government was wherever he was; in his later years, he spent much time outside of Rome. He even named two months after himself: Germanicus and Domitianus, which had been September and October. Jealous and suspicious, he recalled the popular Agricola, one of the conquerors of Britain, in order to stem the latter's popularity. A group of assassins killed Domitian in 96, and Nerva took the throne. The new emperor named Trajan governor of Upper Germany and, a year later, formally adopted him, designating him as heir to the throne. Far more at home in the military than in government, Trajan stayed with his army for a time when, in January 98, he got word that Emperor Nerva had died. Trajan took time to inspect the frontiers along the Danube and the Rhine. He also had a bridge over the Danube River; it was the longest arch bridged in the world for a century. He returned to Rome in summer 99 to great acclaim, not least because he came on foot and presented himself to the people at large. Trajan was a successful commander, defeating the Dacians and Parthians, both longtime enemies of Rome. This led to Trajan's status as the emperor on whose watch the boundaries of the Empire stretched to their widest extent. From Scotland in the north to Egypt in the south, from Mauretania in the west to the Caspian in the east: Roman armies and governors ruled all, an estimated total of 5 million square miles.  Next page > Boundaries and Uprisings > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Nero had left no successor or even a plan for one. His death ushered in the

Nero had left no successor or even a plan for one. His death ushered in the