|

The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain

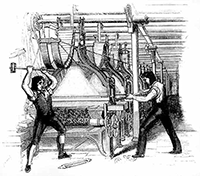

Another change was how and where people lived. Many rural residents gave up their farm life and moved to a city, to live closer to where the jobs were, in factories. Low-income housing was scarce, and workers crowded into such living spaces as well as they could; such masses of people proved to be breeding grounds for shared infections and diseases. Yet another cholera epidemic raged in Britain in 1848. Reformers such as the philanthropist and Scottish textile mill manager Robert Owen campaigned for better working conditions. Parliament in 1833 and 1834 passed the Factory Acts, which bettered working conditions for children and youths. In that same year, the Poor Law created workhouses for the destitute. Trade unions gained many members in the early 19th Century and secured many gains for their members.  Also at this time, the Chartist movement grew into a major political force, protesting all around the country against poor working conditions and the lack of universal male suffrage. Also speaking out against the rise of technology were the Luddites, people who had lost their jobs to machines. Some of these people turned their vehemence directly against the machines, attacking power looms and other devices that epitomized the shift in labor priority. One particularly large such demonstration occurred in Arnold, Nottingham, in 1811. Parliament responded harshly at first, setting the death sentence for those who so destroyed machinery. Such harshness ran its course in time. Still, on the whole, the people of Britain during this time had more and better access to more and better food, drink, and goods than at any time in their history. Factories pumped out product like never before, travel and transport were demonstrably quicker, the standard of living and lifespan for most people rose. Some changes were incremental; others were fundamental. In many ways, industrialized Britain was as never before. First page > From handmade to machine-made > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

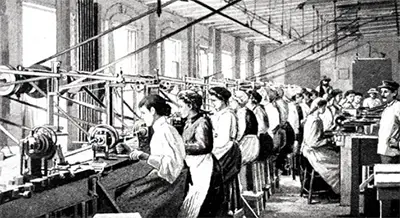

The rise of the steam engine and of productivity increases in textile and iron and other industries brought with it the introduction of the factory system. Many men but mostly children and unmarried women toiled in factories for 12 and perhaps 14 hours a day Monday–Saturday, for often very little money. No laws specifying a minimum wage or a work hours maximum or even a weekend benefit of two days off existed. Workers did not go to work on Sunday only because the religion of the day saw that as a day of rest. Many people had opportunities working in factories that they did not have before; that didn't make the work any less back-breaking, or dangerous. Few if any health and safety conventions were in place. Children commonly had the most dangerous jobs, scurrying around in mines, climbing up and down chimneys, and lying underneath giant machine-driven looms, ready to fix anything that broke.

The rise of the steam engine and of productivity increases in textile and iron and other industries brought with it the introduction of the factory system. Many men but mostly children and unmarried women toiled in factories for 12 and perhaps 14 hours a day Monday–Saturday, for often very little money. No laws specifying a minimum wage or a work hours maximum or even a weekend benefit of two days off existed. Workers did not go to work on Sunday only because the religion of the day saw that as a day of rest. Many people had opportunities working in factories that they did not have before; that didn't make the work any less back-breaking, or dangerous. Few if any health and safety conventions were in place. Children commonly had the most dangerous jobs, scurrying around in mines, climbing up and down chimneys, and lying underneath giant machine-driven looms, ready to fix anything that broke.