|

The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain

In the same way that preindustrial weaving was done by individuals, in homes and workshops, the production of iron was on a small scale as well. Iron manufacturers in preindustrial Britain found it advantageous to locate their facilities near the raw ingredients that they would need for their finished product: charcoal, limestone, and water. The normal method of production was still the blast furnace, as it had been for awhile, but the iron produced wasn't as strong as it needed to be, the manufacturers thought, and so they set about finding a way to innovate, in order to produce more and stronger iron.

Abraham Darby in 1709 became the first to heat coal in order to produce coke in order to smelt iron. The idea of using coal to power an ironworks was a relatively new one, and the collection of coal from pits deep in the ground had spurred Savery, Newcomen, and Watt to pioneer and improve on the steam engine. It was in 1750 that an iron manufacturer, Abraham Darby II, first hooked up a steam engine to power a water wheel to power the making of iron. The next Abraham Darby, the III, built the first cast iron bridge, in Shropshire in the 1770s.

What engineers really wanted to use to make things like bridges was wrought iron, which was stronger still than cast iron. Henry Cort in 1784 invented a method of converting iron to wrought iron by stirring it frequently at a very high heat. This process was called puddling, and it was done in order to remove the impurities from the iron. As well, Cort introduced the idea of using grooved rollers instead of hammers, to make it easier to shape the iron. Manufacturers could then make high-quality iron bars at a much higher rate than before. Improvements in other industries created a skyrocketing demand for iron. Railways in particular needed iron, as did tunnels and bridges and other elements of transportation. Another key buyer of iron at many times throughout the history of England and Great Britain was the government, in order to make weapons. The end of the 18th Century saw British troops fighting in various theatres around the globe, and iron as part of a weapon was still in high demand.

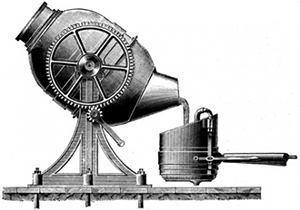

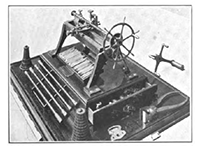

Increases in quality and quantity of iron production naturally led to the same in the production of steel. Henry Bessemer got a patent in 1855 for a process that he developed to mass produce steel from molten pig iron, using oxidation to remove impurities. The process was carried out in a large steel container called a Bessemer converter. The result was steel made cheaply enough yet high-quality enough that it could be sold around the world. And it was. Machine toolsAnother development during the Industrial Revolution was the introduction of machine tools. Businessmen and inventors crafted a boring machine (to enlarge holes), a planing machine (to cut metal), a milling machine (to cut into material and remove it mechanically), and a shaping machine (a high-tech lathe) in order to improve  productivity. Henry Maudslay is perhaps the most well-known name in the advent of machine tools. Around the turn of the 19th Century, he invented a lathe with which to cut metal, which made it possible for workers to craft screws of standard thread sizes, a building block of the later move to interchangeable parts. Maudslay later found work supplying the Royal Navy with rigging blocks for ships and marine steam engines to power boats, and his business crafted the tunneling shield vital to the success of the Thames Tunnel, an engineering marvel through which the London Underground railway flowed. productivity. Henry Maudslay is perhaps the most well-known name in the advent of machine tools. Around the turn of the 19th Century, he invented a lathe with which to cut metal, which made it possible for workers to craft screws of standard thread sizes, a building block of the later move to interchangeable parts. Maudslay later found work supplying the Royal Navy with rigging blocks for ships and marine steam engines to power boats, and his business crafted the tunneling shield vital to the success of the Thames Tunnel, an engineering marvel through which the London Underground railway flowed.

Next page > Transportation > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White