The Hundred Years War

Part 3: Ebbs and Flows

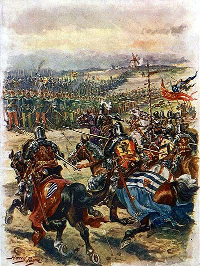

Estimates of the size of the armies differ. What is generally agreed on is that the French outnumbered the English force at least 2-to-1. The greatly outnumbered English nonetheless won a stunning victory, thanks in large part to the longbow and another relatively new weapon, the cannon. This was the first known use of a cannon as a weapon on a battlefield in Western Europe. The victory at Crécy marked the successful military debut of English King Edward III's son, Edward the Black Prince. He followed up that victory with a successful siege of the port city of Calais, which the English took at long last in 1347. Owning control of the English Channel and controlling a port city on the French northwest coast, England stood ready to more easily reinforce the troops already in France.

In the year after the Battle of Calais, 1348, a new enemy arrived: the Black Death. The bubonic plague cut down rich and poor alike, in great swathes across Europe. As many as one-third of the entire European population died of this dread disease. In both England and France, leaders and soldiers quite rightly looked after their own houses for a time.

Fighting resumed in 1356, and the English claimed another victory. Edward, the Black Prince ranged through the French countryside, (employing the chevauchée if only because it didn't require as many men as a full-tilt pitched battle), pursued by France's new king, John II. The two armies met near Poitiers on Sept. 19, 1356, and the Black Prince again showed his military mettle. Again, French forces outnumbered English forces. Again, England more than made up for this deficit with the devastating power of the longbow and the cannon. King John II had left his main force of infantry behind because he wanted to catch up to Edward and thought that the main infantry, which numbered 20,000, would slow him down. After a series of attacks and counterattacks, a well timed cavalry charge by the English turned the corner on the French left and turned the struggle into a rout. The English victory was so complete that English forces captured King John II himself and several hundred members of the French aristocracy. England demanded an exorbitant sum as ransom–equivalent to twice the country's annual income–and the ransom went unpaid. John II later died in captivity. His son, the Dauphin Charles, assumed the running of the country and the war. The English resumed their roaming about the countryside, and the Dauphin Charles set out about raising new funds and troops; but no new battles occurred. The two countries came to terms four years later. As a result of the Treaty of Brétigny, in 1360, Edward III once again was master of Gascony and Aquitaine; in return, he gave up his claim to the French throne. Next page > Looking within > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

The Battle of Crécy began with an archery exchange. The French had a large contingent of crossbowmen, but the English had something new and different and definitely more deadly: the longbow. The crossbowmen who were still alive fled the field, running straight into a French cavalry charge. The range of the longbow was such that it again and again overpowered the French cavalry, all from a distance. Hand-to-hand fighting inevitably ensued, as the two infantries advanced to confront each other. A fierce rainstorm the night before had made the battleground boggy and wet. As well, Edward had taken the precaution of seizing the high ground, and Philip kept ordering charge after charge through the mud uphill toward the waiting defenders. Philip was nearly killed. He had two horses killed underneath him and sustained an arrow to the jaw. Finally, he and his force left the field.

The Battle of Crécy began with an archery exchange. The French had a large contingent of crossbowmen, but the English had something new and different and definitely more deadly: the longbow. The crossbowmen who were still alive fled the field, running straight into a French cavalry charge. The range of the longbow was such that it again and again overpowered the French cavalry, all from a distance. Hand-to-hand fighting inevitably ensued, as the two infantries advanced to confront each other. A fierce rainstorm the night before had made the battleground boggy and wet. As well, Edward had taken the precaution of seizing the high ground, and Philip kept ordering charge after charge through the mud uphill toward the waiting defenders. Philip was nearly killed. He had two horses killed underneath him and sustained an arrow to the jaw. Finally, he and his force left the field.