The Black Death: Killer Medieval Plague

The Black Death was a devastating outbreak of plague in 14th-Century Europe that ultimately killed one-third of the population. Conditions in Europe at this time were perhaps ripe for such a devastation. A plague in 1316–1317 had depleted livestock and crop potential and left in its wake a widespread famine, exacerbated in part because of what has come to be called a "little ice age," a period of longer and colder winters and, consequently, shorter growing seasons and smaller harvests. As well, France, in particular, had been devastated by the Hundred Years War, which officially began in 1337 but had been brewing for several years before that. English armies had ravaged the French countryside in the first decade of the war. Historians still do not agree on the origin of the bubonic plague, although most think that it began in Asia. People living in China, Egypt, India, Persia, and Syria reported suffering through a deadly disease outbreak in the early 1340s. The One group of ships put in at Messina; from there, the plague spread to Marseilles and Tunis and then Rome and Florence; before the year 1348 was out, Bordeaux, London, Lyon, and Paris had been devastated. And the people who lived in the countryside soon discovered that the disease affected their livestock as well; in fact, Europe suffered through a wool shortage after the plague ran its course. The Black Death, which raged from 1347 to 1353, was, in effect, four types of plague: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic.

The bacterium Yersinia pestis caused bubonic plague. (Scientists in later centuries determined this; the people living through it had no conception of germ theory.) The unintended carriers of the dread disease turned out to be black rats, which lived close to people–in their homes, at the places where they worked, and on the ships on which they sailed. The real A person was thus infected:

Another way that the plague spread was through the air. Infected people were prone to coughing, releasing the pathogen into the air nearby; in some cases, it was enough to breathe the same air as someone who was infected. This was an instance of pneumonic plague.

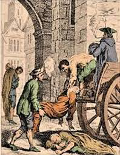

It was also during the reign of Edward III that the Black Death struck England and the rest of the Europe. Conservative estimates are that the During a seven-year period, the plague killed about one-third of the European population, with deaths reaching into the tens of millions. Paris lost half of its people. Some cities, like Hamburg and Venice, lost up to 60 percent. The plague spread less quickly in urban areas because of the distance between people; however, in densely populated cities, the plague-spreading fleas feasted on the helpless residents. In as little as a week after infection, a person could die. In fact, 80 percent of those infected did. A person would fall ill after 3–5 days and die another 3–5 days after that. Those still alive resorted to digging large burial pits to house the enormous number of dead. Anyone known to have contracted the plague was often subject to quarantine, in an attempt to prevent the spread of the disease.

Showing that people at the time didn't completely understand how the disease was contracted or spread, some doctors prescribed treatments like rubbing onions or garlic or even parts of a chicken directly onto bubos, taking a bath in urine, drinking vinegar or arsenic, or eating crushed minerals. Doctors took to wearing special clothing and a distinctive hat and mask, in order to prevent airborne or contact-based infection. They wore gloves and used a wooden cane to examine patients. As people understood more and more the nature of the progression of the disease, they employed more and more strategies to try to mitigate against its spread. In extreme cases, people moved wholesale out of a plague-infested area. If that wasn't an option, then people would try to mitigate against the damage–by rubbing mint or pennyroyal oil on their skin, to discourage flea bites; by folding tightly folded clothes in cedar chests to keep them away from vermin; by maintaining fires in the home as a way to interrupt the spread of the pathogen; and by burning dead rats in hopes of killing the pathogen-carrying fleas as well.

In the wake of this infestation, marriage and birth rates rose, as did donations to the Church. At the same time, people questioned the viability and relevance of the Church because it proved unable to stop the spread of the plague. Governmental authorities came in for criticism as well, for the same reason. Also common were acts of violence, with no distinctions made for class. Overspending resulted in a shortage of goods and a spike in inflation; conversely, some workers benefited because they could demand higher wages in the wake of a labor force shortage. Cities lost large parts of the population, through deaths from the disease and from flight, as panicked residents who could leave did so in droves, fleeing to supposed havens with family and friends (often unintentionally carrying the disease with them). The Black Death began to diminish in 1352 and officially was declared over the following year. It was not the end, however. Less severe outbreaks punctuated the rest of medieval European history. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

plague is thought to have first come to Europe in 1347, when all of the crew on a ship returned from a Black Sea voyage were seriously ill or already dead. Another possible source was via travelers along the

plague is thought to have first come to Europe in 1347, when all of the crew on a ship returned from a Black Sea voyage were seriously ill or already dead. Another possible source was via travelers along the  carriers were fleas that fed on those rats. Such fleas were especially hardy; they could, if their rat host died, transfer to another animal host.

carriers were fleas that fed on those rats. Such fleas were especially hardy; they could, if their rat host died, transfer to another animal host.