King Edward I of England

Part 2: Scotland and Wales

Edward's wife, Eleanor, died of illness in 1290. She was 49. He had her buried in Westminster Abbey.

Six years later, Edward married again, to Margaret of France, whose father was King Philip III. Edward was 60; Margaret was 17. They had three children together. Edward was briefly at war with France over Gascony, which Edward technically still owned. He made alliances with the King of Germany and with other powerful European nobles but, in the end, could not count on that support. His marriage to Margaret ended the war with France. On the domestic front, Edward managed to keep his barons in line while also bringing in large sums of money, succeeding where his father and grandfather had failed. He also followed in his father's footsteps by persecuting the Jewish population and imposing on them severe amounts of taxation. The final step in his Jewish policy was to expel all Jews from England, in 1290, and seize their lands and money. Edward also directed an extensive review of criminal and property law, resulting in the Statue of Westminster 1275 and the Statute of Westminster 1285, clearly setting out categories of offense and the punishments thereof. The end result was the Crown's asserting that all liberties enjoyed by the people of the realm came with the consent of the Crown. As well, he remade the personnel of government, from the highest level of chancellor down to the local level in the person of the sheriffs, replacing his father's men with his own. And, he made a habit of calling and retaining Parliament, something his father was nearly loathe to do. Edward was known as a regular attendee of church services. As well, he gave regularly to the church from his own private funds.

He also had a fascination with King Arthur, the historical/legendary Dark Ages king of a united Britain. Edward and Eleanor went in person to Glastonbury in 1278 in order to witness the revelation of the remains of bodies that were discovered at the abbey there and that the monks claimed were Arthur and his wife, Guinevere. Edward and Eleanor were so taken with the story that they gave the abbey a lot of money for the construction of a new tomb for the bones. Edward also sponsored Round Table events in 1284 and 1302, featuring tournaments and feasts in the spirit of Arthur's fabled association of knights. Edward it was who commissioned the construction of the giant Round Table that still hangs on the wall of the Great Hall in Winchester. A dispute in Gascony, part of Aquitaine, escalated in 1294 into war between England and France. It was during this war that France and Scotland began the Auld Alliance, a long-running mutual defense pact against England. The 1303 treaty that ended the on-again-off-again conflict restored Gascony to England; sealing the deal was a royal marriage, of Edward, the son of Edward I to Isabella, the daughter of France's Philip IV. Edward, having vanquished Wales and still determined to own all of Britain, turned next to Scotland, where King Alexander III had died, his only heir being his young granddaughter, Margaret, known as the Maid of Norway because her father was Norway's king. Edward proposed a marriage between Margaret, who was 3, and his oldest surviving son, Edward, who was 6. The Scottish nobles agreed and sent for Margaret to come from Norway to marry Edward (the younger). Margaret died on the journey, and the Scottish succession was left in disarray. No one noble was able to convince enough of the others to support him as King of Scotland. This period came to be known as the Great Cause. The nobles appealed to Edward to decide. The two most powerful were John Balliol and Robert Bruce. Edward chose Balliol. Edward, convinced that the Scottish nobles had appointed him the equivalent of an overlord, made increasingly authoritative demands of Balliol and of Scotland. Edward, fighting against France, demanded that the Scottish nobles provide manpower and money on Edward's behalf. The Scottish nobles refused, instead making an alliance with France (later to be known as the Auld Alliance) and rising up in revolt, launching an attack on Carlisle. An incensed Edward sent an English army into Scotland, in 1296. In the ensuing battle, the Scots proved no match for the English and Edward even seized Balliol, sending him as a prison to the Tower of London. Edward became known as the "Hammer of the Scots." He had destroyed Berwick taken Dunbar, and seized much of the country and its riches. Also in that year, Edward seized the Stone of Destiny, on which all Scottish kings had been crowned for time immemorial, and sent it to Westminster Abbey. Even with this infusion of Scottish money, Edward didn't have enough to build the sort of castle enforcement that had kept Wales in check, and Scotland took advantage.

The Scottish rebels rallied behind the leadership of William Wallace and Andrew Moray, the former more than the latter, and won a few victories over the English. The most notable of these Scottish victories was at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, routing the English forces, who were led by John de Warenne. Englishmen and Scottish men parried and thrusted for a time, with the English gaining a great victory at the Battle of Falkirk, in 1298. This time, Edward had marched north with the army, buoyed by the support of a significant number of nobles thanks to Edward's renewed commitment to Magna Carta. After the victory, he named as rulers of Scotland three regents: Robert the Bruce (grandson of the original claimant), John Comyn, and the Bishop of St. Andrews. Wallace and the Scots fought on, storming Stirling Castle in 1304. He was betrayed by one of his own, Sir John de Menteith, and handed over to Edward, who had him executed, in 1305. Not long afterward, Bruce played a part in the death of Comyn and had himself crowned King of the Scots, in 1306. Edward determined to teach the Scots yet another lesson and marched north yet again. During this struggle, Edward showed his cruel side by having Bruce's sister imprisoned for a handful of years. He had also ordered William Wallace killed in a particularly gruesome way. The English and Scottish armies traded victories for a time, but the Scottish forces began to gain the upper hand. Edward persisted, wanting to lead his army in one more victory. He was so weak by this point that he had to be carried in a litter. He contracted dysentery and died at Burgh on Sands, just south of the Scottish border, on July 7, 1307. He was 68. He was buried with great ceremony in Westminster Abbey, and his oldest son was crowned King Edward II. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Once he was solidly on the throne, Edward set about on an ambitious plan to conquer the whole of Britain.

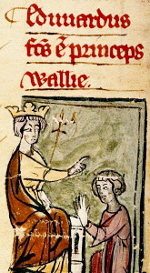

Once he was solidly on the throne, Edward set about on an ambitious plan to conquer the whole of Britain.  building a number of large castles in the process. The Statue of Rhuddlan officially made Wales a province of England. Edward declared his oldest son, also named Edward, the Prince of Wales. He also had Llywellyn's infant daughter, Gwenllian of Wales, imprisoned at Sempringham Abbey. She lived out her life there, as a nun.

building a number of large castles in the process. The Statue of Rhuddlan officially made Wales a province of England. Edward declared his oldest son, also named Edward, the Prince of Wales. He also had Llywellyn's infant daughter, Gwenllian of Wales, imprisoned at Sempringham Abbey. She lived out her life there, as a nun.