Magna Carta: Inspiration for Modern Governments

Magna Carta was a 13th-Century pact between a king and 25 of his most powerful subjects to cooperate more fully in the future. Neither side kept their word, but the resulting agreement is widely regarded as one of the inspirations for the U.S. Constitution and for British common law and civil liberties.

The king was England's King John, who had been on the royal throne since 1199. The subjects were barons, powerful landowners who were seeking some respite from the king's seemingly never-ending requests for war taxes and what the barons saw as arbitrariness in the way royal pronouncements and taxes were handed down and enforced. For much of the time that John was on the throne, his country was at war with France. This was a continuation of a struggle begun many years before. John had succeeded Richard I, the great Crusader hero, and had actually assumed many of Richard's powers while the king was away in the Holy Land. England as the 12th Century dawned controlled considerable lands in what is now France, including Anjou, Aquitaine, Normandy, and Poitou. French forces were striving to retake the lands they once owned and had regained control of a significant portion, meaning that lands owned by many English barons were back in French hands. To finance the war to maintain English hold on these once-French lands, King John had introduced a series of taxes and later imposed harsh sentences on people who could not pay those taxes. So the war wasn't going well despite an influx of new money from landholders, and the French re-possession of lands meant the loss of income and titles held by many English barons. John was also having troubles with the Catholic Church at the time, specifically with Pope Innocent III. The pope had named Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury, but King John had wanted someone else in that position and refused to allow Langton to take up the appointment. In return, the pope excommunicated John and banned church services throughout the country. The king relented and appealed for the pope's grace. The result was a lifting of the excommunication and an accompanying slew of tributes, further draining the royal treasury. A group of barons had had enough early in 1215 and took up arms against their king. This was not exactly a new phenomenon, but it had a new result. The barons captured London in May and then captured John himself at Windsor a few weeks later. The barons presented John with a list of demands that became Magna Carta. John affixed his royal seal to a list of these demands on June 15, and the barons renewed their oath of fealty to him on June 19, at a meadow in Runnymede, west of London. (Many of the provisions in Magna Carta appeared also in the Coronation Charter signed by King Henry I in 1100.)

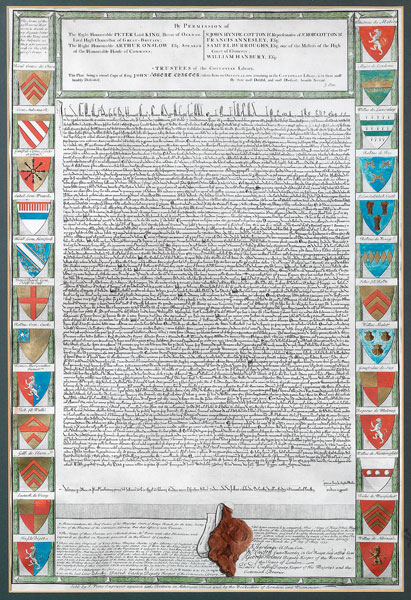

Magna Carta, meanwhile, had been copied and re-copied and distributed throughout the land. Among the things that the king and the barons agreed to in the negotiations that had produced the "Royal Charter":

The writers of Magna Carta wrote in Latin (with English and French versions coming later). They did not divide the text into sections. The noted legal scholar Sir William Blackstone did that, in 1759. Blackstone's numbering system is still in use. One large section now called Clause 61 incorporates the medieval legal practice of distraint, allowing a committee of "enforcer" barons who could, if they deemed it vital to the eventual success of the realm, overthrow the king and seize his possessions.

The barons who served as "enforcers" of Magna Carta were the following:

The Charter, annulled by the pope not long after its inception, was updated and re-issued through the years. Many of the particulars no longer apply to British common law, but many still do. Many of the ideas put forward in Magna Carta formed the basis for other famous governmental blueprints, including those of the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, and other countries of the Commonwealth. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

John had made the promises that became Magna Carta in order to avoid a wider confrontation. He didn't have any more money or support in June than he had in May, when the barons had occupied London. The king's intention not to abide by Magna Carta became evident not long after the "agreement." The result was another war, called the First Barons War, with the heir to the French throne, Prince Louis, invading England, capturing London, and proclaiming himself king. Louis wasn't crowned, however, and John died soon after. The choice for king then was John's 9-year-old son, who became King Henry III.

John had made the promises that became Magna Carta in order to avoid a wider confrontation. He didn't have any more money or support in June than he had in May, when the barons had occupied London. The king's intention not to abide by Magna Carta became evident not long after the "agreement." The result was another war, called the First Barons War, with the heir to the French throne, Prince Louis, invading England, capturing London, and proclaiming himself king. Louis wasn't crowned, however, and John died soon after. The choice for king then was John's 9-year-old son, who became King Henry III.