The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry is one of the most famous artworks of the Middle Ages. A large embroidered cloth, it contains illustrations of the events that led up to the Norman Conquest of Britain.

The tapestry itself is 20 inches tall and nearly 230 feet long. Historians think that Bishop Odo of Bayeux, in France, commissioned the creation of the tapestry, in the first decade after the Battle of Hastings, who took place on October 14, 1066. On that day, a coalition of armed forces under the command of William, Duke of Normandy defeated the Saxon defenders led by King Harold of England. William's victory resulted in the Norman Conquest, which brought many elements of change to Anglo-Saxon Britain. (Odo himself features in one scene, rallying the Norman troops.)

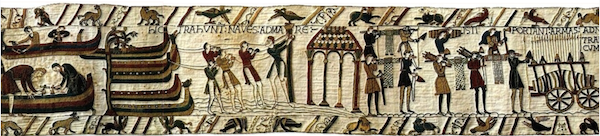

The events depicted begin in 1064, when King Edward the Confessor ordered his brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson, to go on official business to Normandy in order to offer the right of succession to the English throne to William, Duke of Normandy and Edward's cousin. Two years later, when King Edward died, Harold secured English support for his own claim to the throne and was crowned King of England. Not satisfied, William mounted an invasion force and, in September 1066, crossed the English Channel with a force of 7,000 men and 2,000 horses.

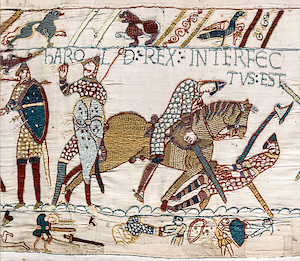

The Bayeux Tapestry has vivid depictions of the episodes in this story. Infantrymen wield weapons, and cavalrymen power their horses through the thick of battle. The subject matter is at times all too real: Depicted are severed limbs and bloody confrontations, Norman cavalry swooping down on the vaunted Saxon shield wall.

One particularly famous part of the Tapestry is of a man on horseback taking an arrow in the eye, presumably killing him. This was long thought to have been a depiction of the death of King Harold, an event that turned the tide of the battle. It's not just the battle that is the focus of the scenes on the tapestry. Along the tops and bottoms of the battle scenes are depictions of animals such as birds, deer, dogs, and lions and imaginary creatures like centaurs (man-horse hybrids) and griffins (eagle-lion hybrids). Brilliantly illustrated is a bright star in the sky, now known to be Halley's Comet, which appeared in 1066. As well, Latin words dot the embroidered landscape. In all, the Tapestry has dozens of scenes, which a viewer can see while walking from left to right. It ends rather abruptly because the end of the Tapestry was lost centuries ago.

The tapestry has a varied history. It was listed in French annals in the late 15th Century, in an inventory of the contents of Bayeux Cathedral, and then not again until nearly three centuries later. The French Revolutionary government seized the tapestry in 1792 with the intention of using it to cover military wagons, but an enterprising lawyer spirited it away and kept it for a time. In 1803, the Fine Arts Commission took possession of the tapestry and sent it to the Musée Napoléon. In the mid-19th Century, the Tapestry was in a purpose-built room in the Bibliothéque Publique. French authorities hid it away during the waning days of the Franco-Prussian War, when a Prussian takeover of Paris seemed imminent. During World War II, the German Gestapo seized the Tapestry and stored it in the Louvre. The liberation of Paris brought a French repossession of the Tapestry, which was then sent to the Bayeux Museum, where it is displayed now.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White