The Battle of Megiddo

The Battle of Megiddo was a historic victory by Egypt over a coalition of forces in the Middle East in the mid-15th Century B.C. The victory, led by Pharaoh Thutmose III, set the stage for a large expansion of the Egyptian Empire.

Thutmose III had technically become king when his father, Thutmose II, died in 1479 B.C. However, the younger Thutmose was very young and so Egyptian officials named his stepmother, Hatshepsut, as co-regent. Hatshepsut took the reins of government herself and ruled for 15 years as pharaoh. When she died, in 1458 B.C., Thutmose III became king all by himself. A change in leadership often brought with it challenges from within and without. In this case, Thutmose III had to put down rebellions in the east, specifically with the civilizations in Canaan and Syria. One of the peoples against which Thutmose and his army contested were the Mittani; the two powers eventually made peace. Elsewhere, the leaders of the city of Kadesh convinced a number of tribes living in Canaan to rise up and challenge the might and reputation of Egypt. A coalition of forces (including the Mittani, who had abandoned their peaceful stance toward Egypt) gathered at the city of Megiddo, an important trade center and fortress in what is now Israel but was then northern Canaan. The city was a key point on the Via Maris, a main trade route between Egypt and Mesopotamia. Thutmose III, confident from his role as head of the armies from a young age, assembled a large force and marched on Megiddo, in the spring of 1457 B.C. One significant factor in his favor was that even though the Egyptians had not fought any major campaigns while Hatshepsut was pharaoh, they had kept up their military training and had honed their forces and tactics to sharp precision, augmenting their traditional weapons and methods with those that they gained through the Hyksos occupation.

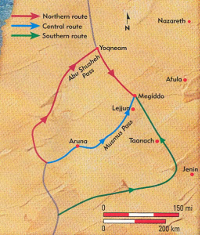

The normal route of approach from Thebes to Megiddo was through the Qina Valley, along one of two wide roads that would have been good for a large army to travel on and maintain cohesion but would also have announced that an invasion was imminent. The Kadesh-led forces had set up in a series of extensive defensive positions in order to intercept the Egyptians before they got near the city. Thutmose III had other ideas, however. The third route into Megiddo was through a narrow pass. Thutmose had called a war council, at which his generals had advised against going through this pass because the army would have to go single file and would be at risk of ambush, certainly during their time in the pass but also at the other end, where enemy forces would surely be waiting. Thutmose ignored their counsel, preferring the element of surprise. He led his army to the town of Aruna and then through the narrow pass, bypassing the defenders and arriving behind their fortifications. The pass was so narrow that the soldiers had to carrying the wagons and chariots that they had dismantled. (Horses went through single file as well.) The Egyptians found no enemy waiting for them and, in fact, were able to get a night of sleep, near the Qina Brook. (It also took a long time for the entirety of the army–tens of thousands strong–to make it through the narrow pass going one at a time, even at a fast march.)

The next day, the Egyptians, Thutmose III at the forefront, had the element of surprise, fell on their enemies with devastating swiftness and ferocity, and drove them into dispersion. As happened more often than not in ancient times, however, the victorious army took advantage of the flight of the conquered army to loot what the fleeing soldiers had left behind. By the time that Thutmose had restored order, the remnants of the coalition forces had melted back into the city. The pharaoh had to besiege the city. Megiddo had been fortified and was well set up to be defended by a much smaller force than the one attacking it. The Egyptians were up to the challenge, having prepared for a sustained campaign. They dug a moat around the city, then erected a defensive wall, behind which they waited. Rather than try to take the city by force, the Egyptians denied the people within the city walls the food and other supplies that they needed to survive. After seven months, the defenders surrendered and opened the gates to the city. Among the spoils were tens of thousands of horses and chariots; thousands of weapons and sets of armor; large stores of grain; very large numbers of livestock; and a large number of jewels, gold, silver, and other precious metals. Thutmose spared the lives of the readers of the rebellion, on the condition that they swore never to rise up again in rebellion against him or his successors; he did take away their titles and their riches, though. He did not order the city destroyed. The Egyptians took the children of the defeated leaders back home with them, educating them and then sending them back after a number of years. Those children of foreign royals were effectively hostages, but they did have more freedom in their new lives in Egypt than did the slaves and prisoners of war that Thutmose also claimed as the spoils of war.

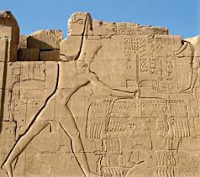

The Egyptian victory at Megiddo was one of the most important in the ancient civilization's long history. It was one of 17 campaigns that Thutmose III led in his long and storied career that resulted in his being called "the Napoleon of Egypt." He pressed his dominance over much of Canaan and campaigned into Mesopotamia, finding that his reputation as the victory at Megiddo preceded him and that several possible antagonists preferred monetary tribute to staged warfare. It was also one of the very first ancient battles for which full details of the battle were written and have been preserved. Tjaneni, the pharaoh's personal scribe, produced an extensive report of the Egyptian army's travels and travails that the pharaoh later ordered carved into the walls of a temple at Karnak. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White