The Hyksos

The Hyksos period in Egypt was a time of multicultural borrowing and assimilation that began slowly and relatively peacefully, ended suddenly and violently, and resulted in an overall improvement of Egypt's capability to sustain its empire.

Differing traditions paint different pictures of who the Hyksos were, where they came from, and what they did when they arrived in Egypt. What is known for certain is that they ran the show for one or perhaps two centuries.

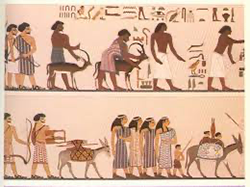

The name is commonly written as Heqau-khasut, which the Greeks turned into Hyksos, which translates into English most commonly as "Rulers of Foreign Lands." The Hyksos are generally believed to have come from the east and to have settled in the eastern Nile Delta, in the 17th or 16th Century B.C. They are thought to have arrived in fits and starts, as a collection of rulers and nobles, establishing a power base in the Lower Egypt port city of Avaris, during the 13th Dynasty. Near the end of this dynasty, Egypt was politically and military weaker than it had been for some time; some sources say that a famine and/or plague exacerbated this situation. The Hyksos took advantage of the situation and asserted themselves, in time declaring themselves rulers of Egypt. Sources from ancient and medieval times have described the arrival of the Hyksos as an invasion, as if they came suddenly and took control by conquest. Little archaeological evidence has been found to corroborate these assertions; the lack of such evidence has led many historians to conclude that the Hyksos takeover of the Egyptian apparatus of government was a peaceful one, if not a collaborative one. If the Hyksos assumed control by violent means, they went out of their way to make peace with the people that they conquered–adopting the Egyptians' religious beliefs, modes of attire, and attitude toward their neighbors, speaking the local language, and installing Egyptians into key positions into the new government. In reality, the Hyksos ruled in the north, in Lower Egypt, but not in the south, in Upper Egypt. From Hermopolis south, Egyptians still ruled but were the equivalent of vassals to the Hyksos overlords. One way in which the Hyksos took and maintained power was through the use of advanced weaponry, such as chariots and composite bows and other weapons made of bronze, like the scimitar. They had these weapons, the Egyptians did not, and this is why early sources concluded that the Hyksos' takeover of Lower Egypt was a violent one. However they took power, the Hyksos maintained it, if they needed to, by employing new weapons and techniques of using them.

Some evidence of the use of horses and chariots in battle can be found in earlier times, but it was not until the Hyksos era that Egyptian military forces used these sorts of weapons in any sort of meaningful way. The combination of a charioteer bearing down on infantry while bowmen in the chariot fired armor-piercing arrows from composite bows was a powerful one indeed. Reinforcing the idea that the Hyksos were more interested in some sort of cultural partnership, they taught the Egyptians what they knew about making and using these weapons. Some sources tell of periodic uprisings against the "invaders" and of efforts to put down such uprisings. Hyksos forces are known to have sacked Memphis. Nonetheless, the Hyksos period was one of relative peace, internally and externally. Historians refer to the Hyksos era as the Second Intermediate Period, which began with the 15th Dynasty. The names of few Hyksos kings are known, primarily because in the inevitable "reconquest," the Egyptians removed the names of the Hyksos rulers from kings lists. Despite this, other sources contain the names of some Hyksos kings, such as Sakir-Har, Khyan, Khamudi, and Apepi.

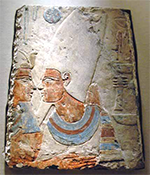

The last of those presided over the demise of Hyksos rule in Lower Egypt. Apepi ruled in the mid-15th Century B.C. By this time, the kings and people of Upper Egypt had strengthened Thebes and the lands around it, along with their military, and felt compelled to confront the Hyksos-led forces of the north. A Theban king named Kamose led an army into battle against the Hyksos and was mildly successful. His brother Ahmose (right), succeeding as King of Thebes, was the one who led the Egyptians to victory over the Hyksos and convinced them to leave not only Avaris but all of Lower Egypt. The Egyptians' success was so complete that it included a further campaign into Palestine, highlighted by a six-year siege that resulted in the further flight of the Hyksos to what is now Syria, after which they disappeared from history. Ahmose became King Ahmose I, founder of the 18th Dynasty, beginner of the New Kingdom, and Lord of the Two Lands. He improved on the Hyksos model of the military and used it to conquer lands surrounding Egypt, creating a buffer zone of sorts that served to protect the civilization in future years from surprise attacks from neighbors with violent intent. What the Hyksos left behind was a series of improvements: in fighting, in metalworking, in farming, in crafting. Egyptians learned to make and use new weapons, of sturdy bronze, and enjoyed the greater accuracy and devastating potential of the Hyksos-introduced weaponry. They learned new ways of One other benefit that the Hyksos provided the Egyptians was in the historical record. The Hyksos king Apepi set his scholars on a program of copying old papyrus scrolls and then carefully storing them, ensuring that they would not be lost because of conquest or natural disaster. Some of Ancient Egypt's most important scrolls (such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, the Westcar Papyrus, and an ancient surgical handbook) survived in this way. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

irrigation, which improved the already vaunted Egyptian agriculture method, and new ways to grow and harvest fruits and vegetables. They created new and improved ceramics, courtesy of an augmented potter's wheel. They crafted linen of higher quality, thanks to the Hyksos-introduced vertical loom.

irrigation, which improved the already vaunted Egyptian agriculture method, and new ways to grow and harvest fruits and vegetables. They created new and improved ceramics, courtesy of an augmented potter's wheel. They crafted linen of higher quality, thanks to the Hyksos-introduced vertical loom.