|

|

The Life and Successes of Alexander the Great

|

Share This Page

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow This Site

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part 6: Taking Over a Huge Empire

Meanwhile, Alexander marched south, to Babylon. This ancient capital was a fabled city, home to the Hanging Gardens and the throne of Nebuchadnezzar and all manner of other rulers. Babylon, the gateway to the Persian Gulf,  was known to be a heavily fortified city. The residents had withstood sieges during the rules of Cyrus the Great and Darius I. Alexander assumed the worst and readied his men for a long struggle, possibly on par with the one needed to subdue Tyre. But when the Macedonians reached the ancient capital, they found the gates to the city thrown wide open and the welcome mat rolled out. Whether the Babylonians were ready for a new leader or they knew that they couldn't withstand an attack by the formidable invaders, Alexander didn't care. He was received as a hero and treated like a god. was known to be a heavily fortified city. The residents had withstood sieges during the rules of Cyrus the Great and Darius I. Alexander assumed the worst and readied his men for a long struggle, possibly on par with the one needed to subdue Tyre. But when the Macedonians reached the ancient capital, they found the gates to the city thrown wide open and the welcome mat rolled out. Whether the Babylonians were ready for a new leader or they knew that they couldn't withstand an attack by the formidable invaders, Alexander didn't care. He was received as a hero and treated like a god.

As he had done throughout his conquests, Alexander left the local government in place, swearing the leaders to loyalty to him and him alone. He sat on the throne of the Great King and attended to the people's wishes for a time. In this, he saw the big picture: He would need more than soldiers to capture the hearts and minds of the Persian people. It was then that his vision to grow grand, if it wasn't that big already. It was in Babylon that Alexander began to really see himself as the bridger between two worlds, as the leader of a new Greco-Persian civilization that would incorporate the best of the both and eliminate the worst of each. He took a great interest in the Persian religions and listened patiently to its priests.

His men, however, had other ideas. They grew impatient, both with Alexander's attention to eastern ideals and to what they saw as his dallying in a foreign capital. They wanted to keep moving: If they weren't headed home, then they wanted more conquests. To that, Alexander agreed.

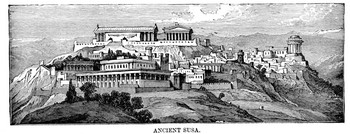

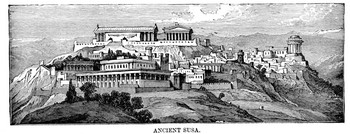

The Macedonian army, its numbers swelled by Persian recruits, then marched to another of the great Persian cities, Susa. Again, the outcome was the same, although the people there were not as welcoming as the Babylonians had been. Still, Alexander gave his men large shares of the spoils before sending it back to Macedon. The Macedonian army, its numbers swelled by Persian recruits, then marched to another of the great Persian cities, Susa. Again, the outcome was the same, although the people there were not as welcoming as the Babylonians had been. Still, Alexander gave his men large shares of the spoils before sending it back to Macedon.

Onward they went, moving ever deeper into the heart of the Persian Empire. Alexander's stubbornness required that his men march through a blinding snowstorm, but they did it readily enough. The next target was Persepolis, which was  in technicality the chief city of the empire. Babylon was the fabled ancient capital, yes; but Persepolis was the real seat of power, the home of the palace of the Persian kings. If Alexander showed reverence for Babylon, what would he do in Persepolis? Some of his men worried that they would be stuck again in some faraway city; many missed their families and their home life terribly. But they were devoted to Alexander. They reveled in the riches that they found, riches beyond imagining. They reveled in the celebration of the sacking of yet another Persian city. But they were understandably shocked when Alexander set fire to the royal palace itself. in technicality the chief city of the empire. Babylon was the fabled ancient capital, yes; but Persepolis was the real seat of power, the home of the palace of the Persian kings. If Alexander showed reverence for Babylon, what would he do in Persepolis? Some of his men worried that they would be stuck again in some faraway city; many missed their families and their home life terribly. But they were devoted to Alexander. They reveled in the riches that they found, riches beyond imagining. They reveled in the celebration of the sacking of yet another Persian city. But they were understandably shocked when Alexander set fire to the royal palace itself.

Alexander thought of himself as both the successor to Darius and as the bringer of new light and new civilization. He no doubt thought that the royal palace was a thing of the past, a bridge to older times, before his arrival on the scene. But historians have a difficult time exp laining why he would destroy what at that time was one of the world's most beautiful buildings, full of the world's most beautiful things. Some sources say that he was drunk (both with wine and power) and didn't know what he was doing. Other sources say that it was a symbolic act, as if he, the new king, would arise from the ashes of the old. Whatever the reason or the circumstances, burn the royal palace Alexander did. Thousands of years of history and art went up in flames. laining why he would destroy what at that time was one of the world's most beautiful buildings, full of the world's most beautiful things. Some sources say that he was drunk (both with wine and power) and didn't know what he was doing. Other sources say that it was a symbolic act, as if he, the new king, would arise from the ashes of the old. Whatever the reason or the circumstances, burn the royal palace Alexander did. Thousands of years of history and art went up in flames.

Next page > Proclamation of a New God > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

|

|

was known to be a heavily fortified city. The residents had withstood sieges during the rules of

was known to be a heavily fortified city. The residents had withstood sieges during the rules of  The Macedonian army, its numbers swelled by Persian recruits, then marched to another of the great Persian cities, Susa. Again, the outcome was the same, although the people there were not as welcoming as the Babylonians had been. Still, Alexander gave his men large shares of the spoils before sending it back to Macedon.

The Macedonian army, its numbers swelled by Persian recruits, then marched to another of the great Persian cities, Susa. Again, the outcome was the same, although the people there were not as welcoming as the Babylonians had been. Still, Alexander gave his men large shares of the spoils before sending it back to Macedon. in technicality the chief city of the empire. Babylon was the fabled ancient capital, yes; but Persepolis was the real seat of power, the home of the palace of the Persian kings. If Alexander showed reverence for Babylon, what would he do in Persepolis? Some of his men worried that they would be stuck again in some faraway city; many missed their families and their home life terribly. But they were devoted to Alexander. They reveled in the riches that they found, riches beyond imagining. They reveled in the celebration of the sacking of yet another Persian city. But they were understandably shocked when Alexander set fire to the royal palace itself.

in technicality the chief city of the empire. Babylon was the fabled ancient capital, yes; but Persepolis was the real seat of power, the home of the palace of the Persian kings. If Alexander showed reverence for Babylon, what would he do in Persepolis? Some of his men worried that they would be stuck again in some faraway city; many missed their families and their home life terribly. But they were devoted to Alexander. They reveled in the riches that they found, riches beyond imagining. They reveled in the celebration of the sacking of yet another Persian city. But they were understandably shocked when Alexander set fire to the royal palace itself. laining why he would destroy what at that time was one of the world's most beautiful buildings, full of the world's most beautiful things. Some sources say that he was drunk (both with wine and power) and didn't know what he was doing. Other sources say that it was a symbolic act, as if he, the new king, would arise from the ashes of the old. Whatever the reason or the circumstances, burn the royal palace Alexander did. Thousands of years of history and art went up in flames.

laining why he would destroy what at that time was one of the world's most beautiful buildings, full of the world's most beautiful things. Some sources say that he was drunk (both with wine and power) and didn't know what he was doing. Other sources say that it was a symbolic act, as if he, the new king, would arise from the ashes of the old. Whatever the reason or the circumstances, burn the royal palace Alexander did. Thousands of years of history and art went up in flames.