The Race to the Moon

Four months after the historic Moon landing, astronauts were back in space, headed again to the Moon.

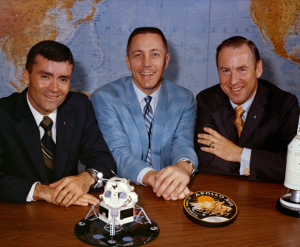

Commander of the Apollo 12 crew was Charles "Pete" Conrad, Jr. Richard "Dick" Gordon was the Command Module Pilot, and Alan Bean was the Lunar Module Pilot. Blastoff was at 11:22 p.m. Eastern Time on Nov. 14, 1969. NASA waived weather rules and launched during a thunderstorm; the launch proceeded without incident, despite a lightning strike. (Bean and Conrad crawled into the lunar module to look for lightning-related damage; they found none.) The lunar module crew of Apollo 12 improved on the landing achieved by the Apollo 11 crew of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin by landing very close to their intended target. The Surveyor III spacecraft had touched down on the lunar surface on April 20, 1967, and Bean and Conrad set down the lunar module just 600 feet away, in the Ocean of Storms, on November 19. They performed two moonwalks (with Conrad exiting the spacecraft first), totaling nearly eight hours, and deployed the nuclear-powered Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package, about 400 feet away from the Lunar Module. One piece of equipment deployed by the Apollo 12 lunar surface crew was the Solar Wind Composition Experiment. This was a repeat of what the Apollo 11 crew had done (and, in fact, the next three lunar missions repeated this as well). The Astronauts deployed an aluminum foil sheet that was exposed to the Sun for varying points of time, with the goal of capturing solar particles. The crew took the foil back to Earth so NASA scientists could do analysis. Other experiments measured the Moon's magnetic field and seismic activity. Bean and Conrad also collected samples of moon rocks, bedrock, and dust (including from an 8-inch-deep trench) and removed pieces of Surveyor 3 (including tubing and the TV camera and cables) to take back to Earth. They returned on November 24. Apollo 13Apollo 13 was supposed to be the third mission to land people on the Moon; instead, it was a triumph of ingenuity over adversity, of determination over nearly impossible odds. The first two Moon landing missions, Apollo 11 and Apollo 12, had succeeded in doing the seemingly impossible: landing humans on another world 252,000 thousand miles away and getting them safely home again, through hostile space and an even more hostile Earth's atmosphere. The crews of those two missions had completed all of their tasks to precision, and Apollo 12 had improved on the Apollo 11 launch location. Commanding the Apollo 13 mission was James Lovell (left, right), who had logged more time in space than anyone else, having flown on Gemini 7 and Gemini 12 and as commander of Apollo 8, the first American The one change to the crew as originally appointed was that Ken Mattingly, who was to have served as Command Module Pilot, had been grounded because he had no immunity to rubella, German measles. Charlie Duke, the backup Lunar Module Pilot, got the disease from one of his children and inadvertently shared it with not only the rest of the backup crew but also with all of the primary crew. Of all six, only Mattingly had not had rubella as a child. Replacing Mattingly was Jack Swigert (left, center), who had been part of the support crew for Apollo 7. (Mattingly never did develop the disease and did finally get his trip into space, aboard Apollo 16.) Launch date for Apollo 13 was April 11, 1970. The launch proceeded without incident and, after a series of burns and maneuvers, the crew were on their way to the Moon. Two days in, on April 13, the crew had just finished a TV broadcast that explained what it was like in the spacecraft and what their mission would entail when they got to the lunar surface when NASA controllers noticed a warning signal on a hydrogen tank in the orbiting craft, which was named Odyssey. Warning signals and lights were not uncommon on Apollo mission; some had been problems that had been overcome, and others had been false alarms. After a discussion between crew and Mission Control, the astronauts proceeded with what they thought would be a routine procedure. Swigert flipped a switch in order to turn on the hydrogen and oxygen tank stirring fans, and moments later the crew felt a large jolt. What happened was a series of bad news: warning lights lit up across the board, on the spacecraft and back at Mission Control, showing a drop in power and oxygen pressure.

Swigert was the one who radioed the news to NASA, saying, "Houston, we've had a problem here." The problems were many. One of the most critical was that the sharp jolt that the crew had felt was actually an explosion that had blown a large hole in one oxygen tank and slightly damaged another. The spacecraft ran on oxygen, which was why the power had been cut. The spacecraft was venting oxygen, and they didn't exactly have a huge backup supply. They would need it not only to power their machines but also to breathe. They turned their Lunar Module into a "lifeboat," a substitute living quarters. They shut down nearly every system in order to preserve power and oxygen. Because of the lack of fuel and power, NASA decided to use the Moon's gravity as a slingshot to send the spacecraft back home, so they actually had to go around the Moon in order to get back to Earth. The return journey would take four days.

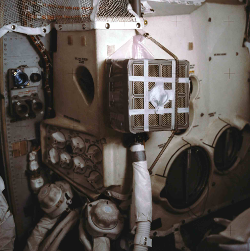

The crew were also causing another problem simply by breathing. Even though they had limited their oxygen supply, they could do nothing about the carbon dioxide that they were venting into the spacecraft cabin just by exhaling. Aquarius had a system to cleanse the air, but it was designed to accommodate two people for two days, not three people for four days. Compounding the problem was the fact that they couldn't "strap on" a system from Odyssey because the two filters were not interchangeable. In one of the space program's more legendary but true examples of genius, scientists on the ground figured out a way for the crew up in space to use the hardware and tools that they had onboard–such as maps and duct tape–to create a workaround; it worked. One of the Mission Control crew working tirelessly to find solutions based on ground-based simulations was Mattingly. Against seemingly impossible odds, the Apollo 13 crew made it home safely. As with the disaster aboard Apollo 1, the Apollo 13 experience prompted thorough investigations from NASA. Next page > Back on the Lunar Surface > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

manned mission to orbit the Moon. Also in the crew was Lunar Module Pilot

manned mission to orbit the Moon. Also in the crew was Lunar Module Pilot