Slave Codes in America

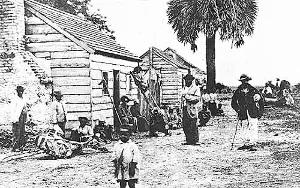

South Carolina instituted its slave code in 1712, basing its laws on those in Virginia and elsewhere. Among the provisions of that colony's code were these:

One element of the 1739 code would seem to have benefited slaves in some small way: they could not work more than 15 hours a day (14 in winter). Working that many hours in a day was still hazardous, though. Georgia and Florida adopted the South Carolina codes as their own, although Georgia, at the insistence of founder James Oglethorpe, initially outlawed slavery. North Carolina's slave codes more closely resembled Virginia's. As new Southern states Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Tennessee, and Texas joined the Union, they adopted variations on earlier states' slave codes and laws. Some of those codes required slaveowners to serve on patrols that roamed the countryside, searching for escaped slaves. Northern states took the lead in abolishing slavery. Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont had done so by the time of the Constitutional Convention, in 1787. (The rest eventually followed suit.) Some of the discussion at that convention involved language in the Constitution that came to be known as the Fugitive Slave Clause. Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 states: "No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, But shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due."

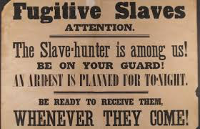

Congress expanded on this idea in 1793 with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. Anyone who gave safe passage or a hiding place to an escaped slave was subject to punishment, as was anyone interfering with a slave's arrest. Further, slave owners and anyone they designated to act on their behalf could search for escaped slaves in states that had outlawed slavery. A runaway slave who was captured would be taken before a judge; in the proceedings, the owner (or "agent," if the owner were absent) would testify that the runaway slave was his or her property, and the runaway slave was denied the right to testify or to have someone speak on his or her behalf. Such proceedings were usually a formality. The law stipulated that anyone found hiding an escaped slave would be fined $500. In the wake of the passage of this law, many African-Americans who were not slaves were captured and taken away into slavery. By and large, Northern states did not act strongly to enforce the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Act. Some Northern states passed personal injury laws that guaranteed fugitive slaves some rights, like the right to a jury trial (not just a hearing in front of a judge); other Northern states passed laws that forbade state officials from participating in hunts for fugitive slaves. An 1842 Supreme Court case, Prigg v. Pennsylvania re-established the supremacy of the federal Fugitive Slave Act and, in effect, nullified such state laws.  As the 19th Century progressed, more and more slaves escaped to freedom in the North, many along the Underground Railroad. This was one of the driving factors behind the updated Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which was part of the Compromise of 1850. Many slaves resisted the harsh conditions of slavery in any way they could: by passive disobedience, by trying to escape, by trying to protect other slaves knowing the punishment for doing so, and, in some cases, by taking up arms. Slave rebellions were few and far between, but they did happen. It was during the Civil War, in 1864, that Congress repealed both Fugitive Slave Acts. (Two years earlier, Congress has passed the Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves, which declared that runaway slaves who had reached "free" territory in the North were free (a repudiation of the Supreme Court decision Dred Scott v. Sanford. Slavery itself was outlawed by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. First page > Early Developments > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White