The Amistad Rebellion

One of the few successful rebellions of African-American slaves was of those aboard the ship Amistad, who won their freedom after a protracted court battle.

The United States and Great Britain had outlawed the international slave trade in 1807. Spain had followed suit in 1811, extending the ban to its colonies. Cuba, a Spanish colony, ignored the ban. The Amistad, in 1839, was carrying several dozen enslaved Africans who had been captured and taken from their homes in Mende, Sierra Leone, in West Africa, to various ports in Cuba. It was aboard the Portuguese ship Tecora that the Mende and nearly 500 other captured Africans had endured the horrendous Middle Passage across the Atlantic, ending up at a slave auction in Havana.

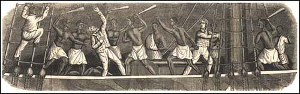

Slave trader Jose Ruiz and an associate, Pedro Montes, had purchased the rights to 49 of the enslaved Mende. Ruiz and Montes were onboard the cargo ship La Amistad when a number of slaves, led by a man named Senge Pieh (who would be more well-known as Joseph Cinqué) killed the captain, Don Ramon Ferrer, and the cook, Celestino (who had taunted the Mende with threats of cannibalism), and then seized control of the ship, on July 1 1839. The Amistad was a cargo ship, not a slave ship with a dedicated slave quarters, so half of the Mende were on deck and all were relatively free to move about on what was to be a short journey. They were manacled, of course, but dealt with that problem by sawing through the chains with a rusty file.

The Mende had spared the lives of Ruiz and Montes, who, in desperation, had agreed to return the Mende to their homes in West Africa. Ruiz and Montes steered the ship eastward during the day but toward the United States at night. The ship proceeded in zig-zag fashion for a time and then ran aground off the coast of New York in August 1839. By this time, the ship's stores were depleted and Cinqueé (right) and the other Mende went ashore to gather more supplies. Finding the Amistad in the meantime was a U.S. Navy survey ship, the Washington, captained by Lt. Thomas Gedney. The Navy took custody of the ship and its occupants and took them to New London, Conn. Gedney then secured a court hearing, at which he stated his right to claim the ship's cargo, meaning what he termed as the slaves onboard. Connecticut at this time had not fully banned slavery. The colony had approved emancipation in 1784, but it was a gradual emancipation, not ending fully until 1848. The hearing ended with the Mende being placed in the custody of the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut and being placed in holding cells for a time.

Cinqué and the other Mende were charged with mutiny and murder. A grand jury heard the case in September 1839. The Spanish slave traders asserted that the Mende were born in Cuba and so were governed by the still-legal practice of the domestic slave trade. The presiding judge, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Smith Thompson, ruled that American courts had no jurisdiction because the mutiny happened at sea in a ship not owned by Americans. The Mende were not released, however, because they were still the subject of competing property claims. Ruiz and Montes had claimed ownership of the Mende, as had the Navy captain, Gedney. Further, the Spanish government wanted the rebellious slaves tried in a Spanish court, claiming as well that the American seizure of the Mende and the ship violated the terms of a 1795 treaty between Spain and the U.S. (Pinckney's Treaty, among other things, stipulated that a ship owned by one nation and seized by the other should be released immediately.) It was Jan. 7, 1840 when the next phase of the legal saga began. The U.S. District Court in New Haven, Conn., was the setting for a hearing before Judge Andrew Judson. The case had attracted considerable attention around the country, and an abolitionist group had secured funds to hire a defense attorney for the slaves. Roger Sherman Baldwin argued that the Mende's natural rights had been violated. A U.S. attorney argued that the slaves were property of Spain and that they and the ship should be returned to that country. Judge Judson ruled that the Mende were free people and should be returned to their homes in Africa. An immediate appeal sent the case to the next level up, the U.S. Circuit Court. The judge in that case was the same as at the grand jury hearing, Smith Thompson, who upheld the lower court hearing. The U.S. Government, on behalf of the Spanish Crown, appealed the decision. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. At this, the highest level of American jurisprudence, two new lawyers joined the case. Arguing for the U.S. Government was Attorney Henry Gilpin. Assisting Baldwin in representing the Mende was former President John Quincy Adams. Among other elements of the arguments made in defense of the Mende's natural rights was the phrase "all men are created equal" from the Declaration of Independence. Baldwin and Adams, however, relied most heavily on the two lower court decisions and urged the high court to uphold those.

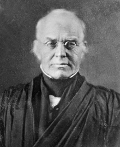

The Supreme Court on March 9, 1841, ruled in favor of the Mende. In the 7–1 decision (with Justice Thompson recusing himself) that agreed with the lower courts' rulings, Chief Justice Joseph Story (right) wrote for the Court that the Mende were not slaves under Spanish law at the time of the uprising and, further, could not be considered as slaves in America, either, because they were in possession of the Amistad when it was seized by the U.S. Navy. The Court voided all property claims, and Cinqué and the other Mende were free to go. The Amistad decision galvanized the abolitionist movement in the U.S. The Mende, however, just wanted to go home. Not all of those who had joined in the revolt were alive by this time. The 39 who were had no money with which to achieve their dream of going home. They found assistance from a number of church and abolitionist groups (including the United Missionary Society), who organized public events that raised money. The Africans sailed for Sierra Leone in 1842, aboard the ship The Gentleman. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White