Confederate General Robert E. Lee

The first of a series of harsh battles in this Overland Campaign took place at the Wilderness. The May battle took place in and around a thicket of undergrowth, negating the Union's numerical superiority. The battle itself was strategically inconsequential. The reaction of Grant after the battle was not: Rather than retreating, he ordered his troops to continue on toward Richmond. Lee was thus forced to issue order after issue of what essentially were blocking maneuvers, designed to keep Grant and the Union armies from reaching Richmond. Spotsylvania Court House was only 10 miles to the southeast of the Wilderness. Lee's men reached it first and had the chance to choose where the battle would be.

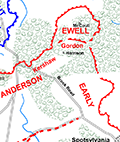

The defenders had arrayed their defenses in a V-shape, with the tip protruding outward. The area inside that V-shape was known as the Mule Shoe, which Lee had countenanced despite some misgivings by his commanders. The first attack occurred late in the day on May 10. Another followed. Neither dislodged any of the defenses. A brief yet spectacular success late in the day was a brief breach into the Mule Shoe led by Col. Emory Upton. Unsupported, the Union troops withdrew. The tactics employed by Upton's men were new: Rather than having his men advance in long lines, stopping to fire and reload at will, Upton formed his troops into groups of 12, 3-by-4, and ordered them to rushed the enemy position, trading firing time for attacking time, with the goal to reach the enemy line and attack with bayonets. Grant was so impressed with Upton, his men, and their success that he promoted Upton to brigadier general and gave orders for others of his troops to employ the same strategy during the next attack. The Union troops spent most of the following day shifting positions, readying for a major assault. Lee, convinced that Grant was going to try to slip by the Confederate emplacements and make a break for Richmond, pulled artillery from within the Mule Shoe and deployed it elsewhere. A predawn Union attack on May 12 breached the Mule Shoe again, this time for good, Lee's order to return the Mule Shoe-defending artillery coming too late. Seeing that further attacks would be just as futile, Grant on May 20 gave the order that Lee had been expecting all along, to move east and then head south. On May 31, Grant ordered the cavalry of Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan to take control of Old Cold Harbor, a key crossroads on the road to Richmond, 10 miles northeast of the capital. When they arrived, they found it occupied by a force of Confederate cavalry and infantry. Sheridan's cavalry succeeded in driving the Confederates out of the crossroads, in the vicinity of the 1862 Battle of Gaines' Mill, part of the Battle of the 7 Days. The following day, a small Confederate attempt to retake the crossroads failed to dislodge the Union troops there. A Union attack later in the day enjoyed more success, but a Confederate counterattack negated that advantage and positions were very much the same as they were at the beginning of the day. Reinforcements poured in on both sides.

Grant, with 108,000 troops at his disposal, ordered a large-scale attack for dawn on the following day. Various communication breakdowns and misadventures bedeviled the Union command structure, and no attack was forthcoming that day. Taking advantage of the lull in the fighting, Confederate troops numbering 62,000 dug in deeper and shored up their defenses tightly and smartly. On June 3, the next Union attack came. Nearly 50,000 strong, it rammed itself at the well entrenched Confederate defenders. In less than an hour, 7,000 Union men lay dead. The range and method of the defensive weaponry was so devastating that Union troops could not even retreat effectively; rather, they dug trenches and climbed in. This battle eventually ended the same way the previous two had, with the departure of both armies. Lee certainly thought that Grant was finally going to attack Richmond. Grant's target, however, was Petersburg, a city 23 miles to the south of Richmond that was a vital railway junction, connecting the capital to the north and North Carolina, in which was still open the port of Wilmington. In a rare success, the Union command outfoxed the Confederate command and, on June 12, got its troops across the James River unopposed and on the road to Petersburg, erecting a 2,100-foot-long pontoon bridge to do so. On June 15, the first fighting began.

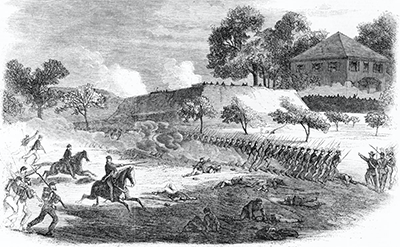

The fortifications at Petersburg were extensive, and the smaller defending force held off the larger attacking force, despite the latter having some temporary successes. Lee, racing back to Petersburg with the Army of Northern Virginia, arrived and began to add his troops to the city's defense, both on patrol and in building further fortifications. On June 16, the numbers were still very much in the Union's favor, with 50,000 troops ready to face off against 14,000 Confederate troops. Attacks by a force under Ambrose Burnside and Winfield Scott Hancock did little damage to the defenders and, after fierce counterattacks, were called off. By June 18, the Union force ringing Petersburg approached 67,000 men in strength. By that time, however, a number of subsequent futile attacks resulting in casualties exceeding 11,000 had convinced Grant that a full-scale assault on the city would result in nothing more than added bloodshed with no purpose. The Union soldiers dug trenches around the city and settled in for a siege. They didn't entirely surround the city, though. Union contingents conducted various raids on the railroads surrounding the city, having varying degrees of success at disrupting those methods of reinforcement. In late June, Grant approved a plan to dig a tunnel underneath the Confederate defenses, plant explosives, and then set them off, using the resulting distraction as cover for a fierce attack that he hoped would break through Petersburg's vaunted defensive fortifications. By the end of July, the 20-foot-deep shaft was 511 feet long and was underneath Elliott's Sailent, a fort right in the middle of the First Corps defensive line. At the end of the shaft was a large chamber that housed 8,000 pounds of explosives. The resulting explosion killed several hundred Confederate troops and disrupted the defensive fortifications, but Union troops severely botched the next part of the plan and casualties mounted considerably. Skirmishes continued into September and through October, and then both sides settled in for the winter. A brief battle at Hatcher's Run in February 1865 was inconclusive. However, the winter, the lack of reliable supply lines, and the length of the siege had taken its toll on the Confederate army. In March 1865, the number of Union troops in the area of Petersburg and Richmond was about 125,000. More were on the way.

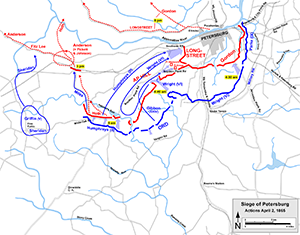

Union Gen. Philip Sheridan and his cavalry had returned by the end of March, arriving from the west. Lee sent nearly 10,000 men under Maj. Gen. George Pickett to Five Forks, to protect that town and its accompanying Southside Railroad. Sheridan and his men easily won the Battle of Five Forks, on April 1. Pickett wasn't even there on the day of the battle and was relieved of his command. The following day, Grant ordered a mass assault on the Confederate line. Union troops made the kind of progress that they had hoped to make many months earlier, forcing the defenders back to the inner ring of fortifications. While riding between the lines to encourage the defenders, Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill, one of Lee's most trusted and longest-serving commanders, fell to Union bullets. Darkness stilled the guns for the day. On that same day, however, Lee had informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the rest of the government that he was leaving Petersburg. Evacuations were taking place even as other defending troops were fighting to protect them. The Union occupied Petersburg at dawn on April 3 and Richmond at the end of that same day. Next page > All Things Must Pass > Page 1, 2, 3,, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

In March 1864,

In March 1864,