Plessy v. Ferguson

One of the landmark decisions of the United States Supreme Court was Plessy v. Ferguson, an 1896 case in which the Court affirmed the doctrine of “separate but equal” in the case of railroad transportation.

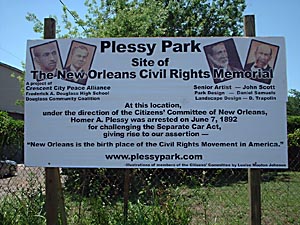

In response to this new rail car law and others of similar restrictive nature, New Orleans formed the Committee of Citizens to focus on achieving the repeal of the Separate Car Act. The Committee chose Plessy to serve as a test case. Plessy did not exactly look like he was of 100 percent African descent. But the law said that he might as well have been. The Committee of Citizens informed the East Louisiana Railroad that Plessy, a man of mixed racial lineage, was planning to challenge the Separate Car Act and then hired a private detective whose job was to arrest Plessy for breaking the law. Accordingly, on June 7, 1892, Plessy went to the Press Street Depot, in New Orleans, and bought a first-class ticket to Covington, La. Plessy got on the “whites-only” car. Railroad staff asked him to leave, telling him that he was required to sit in the “colored” car; Plessy refused to leave. Also on the car on which Plessy then stood was the private detective, who arrested Plessy and escorted him off the train. Plessy was charged with breaking an existing law, and the result was a trial before a judge, John Ferguson. The result was a conviction and a fine, of $25. Plessy’s lawyers had argued that the State of Louisiana, through the Separate Car Act, had denied Plessy his rights under the Thirteenth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment. The judge, Ferguson, thought otherwise, deciding that because the East Louisiana Railroad operated within the state of Louisiana, the state could regulate conduct aboard the railroad. Plessy and the Committee of Citizens appealed the decision to the Louisiana Supreme Court. That court upheld the lower court’s decision, citing as precedent a Pennsylvania law that did exactly what Louisiana’s Separate Car Act did, as well as a Massachusetts Supreme Court ruling that segregated schools were constitutional. Plessy and the Committee of Citizens again appealed, this time to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to take the case. The result was the final decision against Plessy, in 1896. The Court ruled 7–1 that the Separate Car Act, which “implies merely a legal distinction” between the two races, did not violate Plessy’s rights under the Thirteenth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court also rejected the argument of Plessy’s lawers that the Louisiana law implied that blacks were inferior to whites. Writing for the Court, Justice Henry Brown had this to say: "We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it." Eight of the nine justices voted in the case. The ninth member of the Court, David Brewer, did not participate. The lone dissenter in the case was Justice John Marshall Harlan, who was also the only Justice to dissent in a series of decisions known as the Civil Rights Cases, in which the Court invalidated the Civil Rights Act of 1875. In an impassioned dissent, Harlan said, among other things: “In view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved.”

Also on the books for decades was Plessy, until the Supreme Court reversed itself in 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education. The plaintiffs in that case, Thurgood Marshall among them, used some of Homer Plessy’s ideas in their own arguments before the Supreme Court. Homer Plessy continued in his efforts to change existing laws. In his later life, he worked as an insurance salesman. He died in 1925. New Orleans now has a Homer A. Plessy Day (June 7, the day he was arrested), and a park in the city is named after him. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Homer Plessy was a Louisiana shoemaker and abolition activist who had pale skin and largely European ancestors. However, he had a great-grandmother who was African; and under Louisiana law, that classified him as black. An 1890 Louisiana law titled the Separate Car Act required railroads to separate the white and black races as they traveled on railway cars: Railroads had “white” cars and “colored” cars. This law was one of many that served to keep whites and blacks separate in public places.

Homer Plessy was a Louisiana shoemaker and abolition activist who had pale skin and largely European ancestors. However, he had a great-grandmother who was African; and under Louisiana law, that classified him as black. An 1890 Louisiana law titled the Separate Car Act required railroads to separate the white and black races as they traveled on railway cars: Railroads had “white” cars and “colored” cars. This law was one of many that served to keep whites and blacks separate in public places. Harlan warned that the Plessy decision would encourage states to pass more laws like the Separate Car Act, and that is exactly what happened. The legally supported Jim Crow system was on the books in many states for decades; states expanded the “separate but equal” doctrine to include restaurants, restrooms, theaters, drinking fountains, and public schools. In practice the facilities designated for African-Americans were, in large part, inferior to those designated for white Americans.

Harlan warned that the Plessy decision would encourage states to pass more laws like the Separate Car Act, and that is exactly what happened. The legally supported Jim Crow system was on the books in many states for decades; states expanded the “separate but equal” doctrine to include restaurants, restrooms, theaters, drinking fountains, and public schools. In practice the facilities designated for African-Americans were, in large part, inferior to those designated for white Americans.