The 14th Amendment

The 14th Amendment was one of America's three Reconstruction Amendments. Adopted on July 9, 1868, the 14th Amendment was aimed at protecting the citizenship rights and equal protection of all Americans but primarily former slaves.

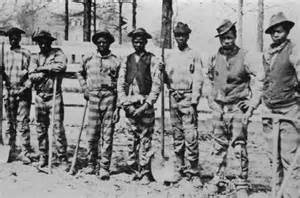

In response, many Southern states created laws or otherwise social conventions known as Black Codes, designed to continue to restrict the rights and privileges of African-Americans. Among things that recently freed slaves could still not do were travel widely, own certain types of property, and have standing to sue or even testify in state court. These were state laws, and aggrieved people did not have the kind of 5th Amendment protection (right to due process under the law) against state infringements that they had against federal infringements. In addition, the law of the land was still Dred Scott v. Sanford, which, even though slavery had been abolished, still ruled out citizenship for the descendants of slaves. Congress went to work to remedy the situation. The result was this: Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State. Section 3. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may, by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability. Section 4. The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void. Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.[1]

The House then turned to an amendment proposed by Ohio's John Bingham. His proposal was a carefully negotiated compromise that enabled the amendment to pass both houses of Congress. (Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, a key supporter of the 13th Amendment, had a hand in efforts to promote the 14th Amendment as well.) Because it was an Amendment to the Constitution and not a proposed law, it did not need to go through the President. Instead, it went to the states, beginning on June 13, 1866. All Northern states voted for ratification; all Southern states except Tennessee refused to ratify the 14th Amendment, leaving the amendment two states short of the required number for passage (28 of 37 states). Congress then passed the Reconstruction Acts, which, among other things, imposed a military government on the states that had not ratified the Amendment and, further, required each such state to ratify the Amendment before being able to attain Congressional representation. On July 9, 1868, Louisiana and South Carolina had voted for ratification, bringing the Amendment into line with the law of the land. It went into effect on July 28, 1868. Significantly, the 14th Amendment did not address voting rights. That would be left to the 15th Amendment. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

The

The  The first step was the Civil Rights of 1866, which guaranteed citizenship to everyone born in America, even if they had been born to slaves, and equal protection under the law. The bill passed both houses of Congress, with more support in the House of Representatives than in the Senate. President

The first step was the Civil Rights of 1866, which guaranteed citizenship to everyone born in America, even if they had been born to slaves, and equal protection under the law. The bill passed both houses of Congress, with more support in the House of Representatives than in the Senate. President